Source: BestColleges

California State University, Dominguez Hills (CSUDH) is partnering with the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) to offer a master’s degree program for incarcerated students.

The HUX program will offer a fully accredited master of arts in humanities and take two years to complete. Students will study topics like religion, incarceration, urban development, and abolition, among others.

“CDCR is proud to partner with CSUDH to further the Department’s commitment in expanding ‘grade school to grad school’ opportunities and also strengthen collaborative efforts with California’s public higher education system,” CDCR Secretary Jeff Macomber said in a press release.

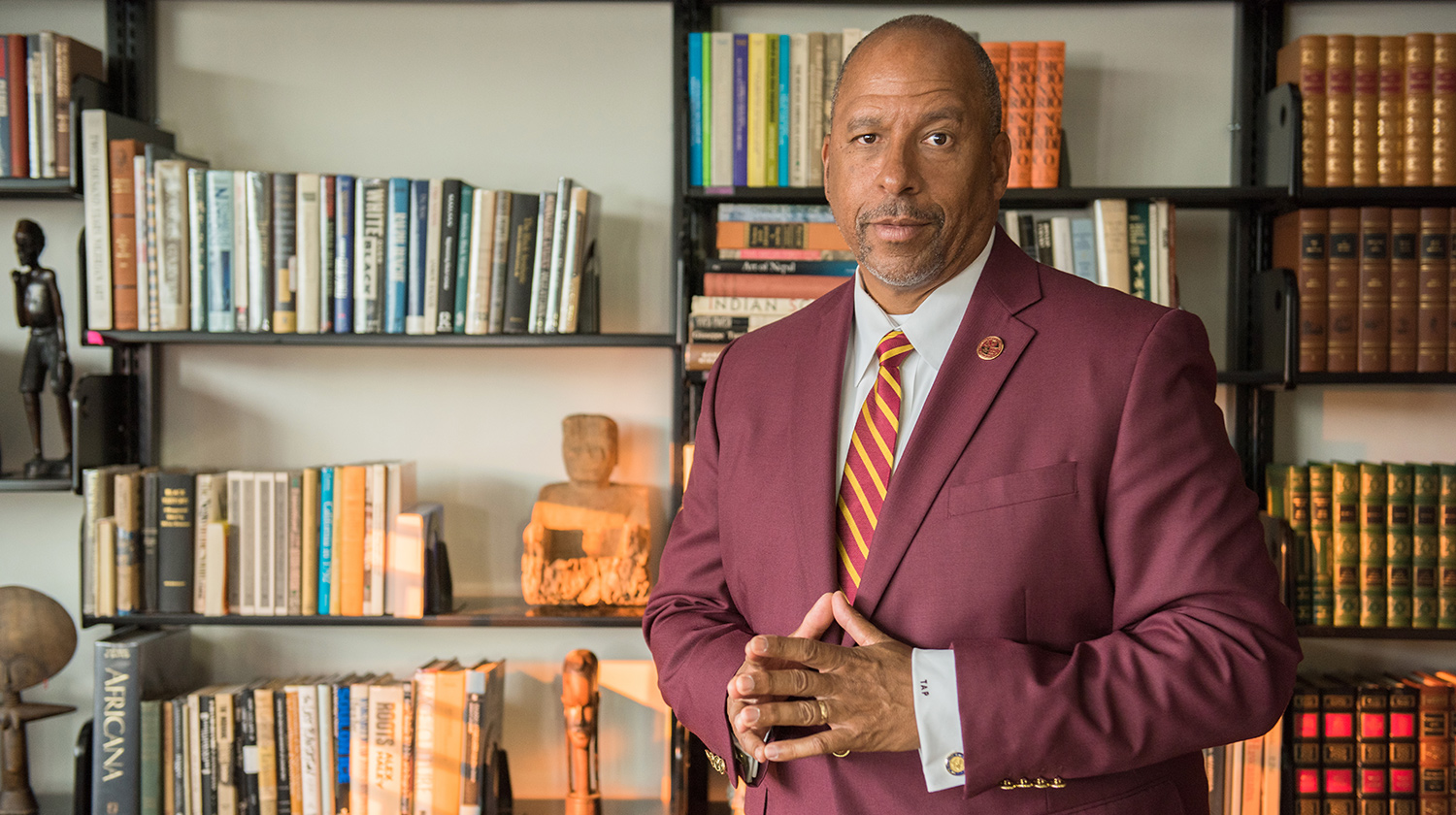

CSUDH President Thomas A. Parham said that the HUX program affirmed the university’s mission of social justice and “transformative education.”

“This historic partnership between California State University and CDCR benefits students‚ and ultimately their families and communities — by distinguishing between what people did and who they are at the core of their being, and recognizing their potential, cultivating their talents, and preparing them to thrive in their paths moving forward,” he said in a press release.

Any incarcerated person within CDCR can apply to join the HUX program, as long as they have an accredited bachelor’s degree and at least a 2.5 GPA in past coursework.

The first cohort begins in fall 2023 and includes 33 students across several facilities, all learning through secure laptops.

History of HUX

The HUX program began in the early 1970s as a correspondence program, which is a distance learning program that’s more independent than your typical online course. But in 2016, fewer students were enrolling, so HUX closed down, director Matthew Luckett told BestColleges.

HUX was open to all students, but incarcerated students could especially benefit from the program’s flexibility and correspondence model to continue their education.

Luckett said he was hired to help HUX students finish their studies once the program closed, but he wanted to ensure incarcerated students could continue their education.

“It seemed like such a shame that we would not have a plan in place for those incarcerated students. So I and several other colleagues on campus started brainstorming and thinking about … how we can make that work,” he told BestColleges.

The solution came by way of funding from the federal government during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act) allotted funding to help those who were negatively impacted by the pandemic.

“In 2020, we were able to get CARES Act funding to help support the rebooting and the modernization of the HUX program,” Luckett said. “We wanted to create a program, not only like a new HUX master’s program, [but] a program that had a starting point, a potent online curriculum, and pedagogy that was then able to export into a correspondence model, if need be, for you incarcerated students.”

Building the Best Program

Luckett wants HUX to improve the prison system. But, at the same time, he doesn’t want it to depend on mass incarceration for program enrollment.

“I thought it’d be more honest to go into thinking [that] this should be a public program. But right now, we’re just going to make it exclusive for incarcerated students. I can see down the line us making a public version of it,” he said.

Students can learn completely online, through correspondence, or a combination of the two.

Luckett describes the network as a “closed system,” excluding, for security purposes, many of the typical ad-ons that normal campus systems have, including Zoom calls, discussion boards, and embedded links in files. Incarcerated students instead have videos, announcements, and weekly check-ins.

“It’s structured and built in a way to ensure the security of its users because they don’t want anybody hacking out or anything like that,” he said. “We have to work within the confines of what’s permissible in terms of security.”

Cost of College

HUX program tuition will cost students roughly $10,500 and be paid by the student or their support people, according to CDCR.

Participants won’t qualify for traditional financial aid, including federal student loans and Pell Grants, according to Luckett.

While access to Pell Grants recently expanded this July to include incarcerated students for the first time since 1994, eligibility does not extend to graduate education.

However, according to CSUDH, scholarships and grant opportunities will be available through the CSUDH financial aid office, and the university is accepting donations to support program participants.

Additionally, in some instances, Luckett said students may be able to receive financial assistance for tuition and textbooks through the Department of Rehabilitation.

“We’re having to really sort of carve out our own funding sphere for the students,” Luckett said. “One of the really great things about working with the Department of Rehabilitation is that now that we have these students in our program, I’m hoping that our success will speak for itself and, then in time, we’ll be able to … diversify the sources of assistance that our students receive.”

Inciting an Impact

About 13.5% of the entire incarcerated population is enrolled in college courses, according to CDCR, including associate, bachelor’s, and master’s degree programs through California’s three public higher education systems.

However, the HUX program marks the first time the department has formally partnered with a public higher education system in the state to offer a graduate degree to incarcerated students.

Luckett says offering graduate degrees to incarcerated students not just helps students, but the state as well. While the HUX program costs $10,500 for two years, it costs the state approximately $212,000 to incarcerate someone for the same amount of time, according to the California Legislative Analyst’s Office.

“The only data we really have is pretty positive — it’s that the recidivism rate for master’s graduates is zero, or virtually zero,” he said. “It seems incredibly likely that our students will not return to prison, which already makes that an incredible dollar-savings proposition.”

Luckett also hopes this first cohort of students will inspire their fellow inmates.

“It affects the people around them because students in their yard see what the graduate education does,” Luckett said.

“It’s aspirational. It gives students something to strive for [and] most of our students are first-generation. So not only are they the first people, oftentimes, in their families to get a bachelor’s degree, but now they’re the first people to get a master’s degree. … It’s a ray of hope in what can ordinarily be a very dark place in prison.”