Growing up in East Los Angeles in the 1970s, Marisela Chávez had a front-row seat to the grassroots activism of the Chicano movement. Her parents, who had immigrated to the U.S. from Mexico as children, brought Chávez with them to meetings, marches, and political organizing events.

“The organization was like an extended family,” says Chávez, now a professor of Chicana and Chicano studies at CSUDH. “I was little at the time, but seeds were planted in me. I saw very strong women who were speaking publicly and being active leaders.”

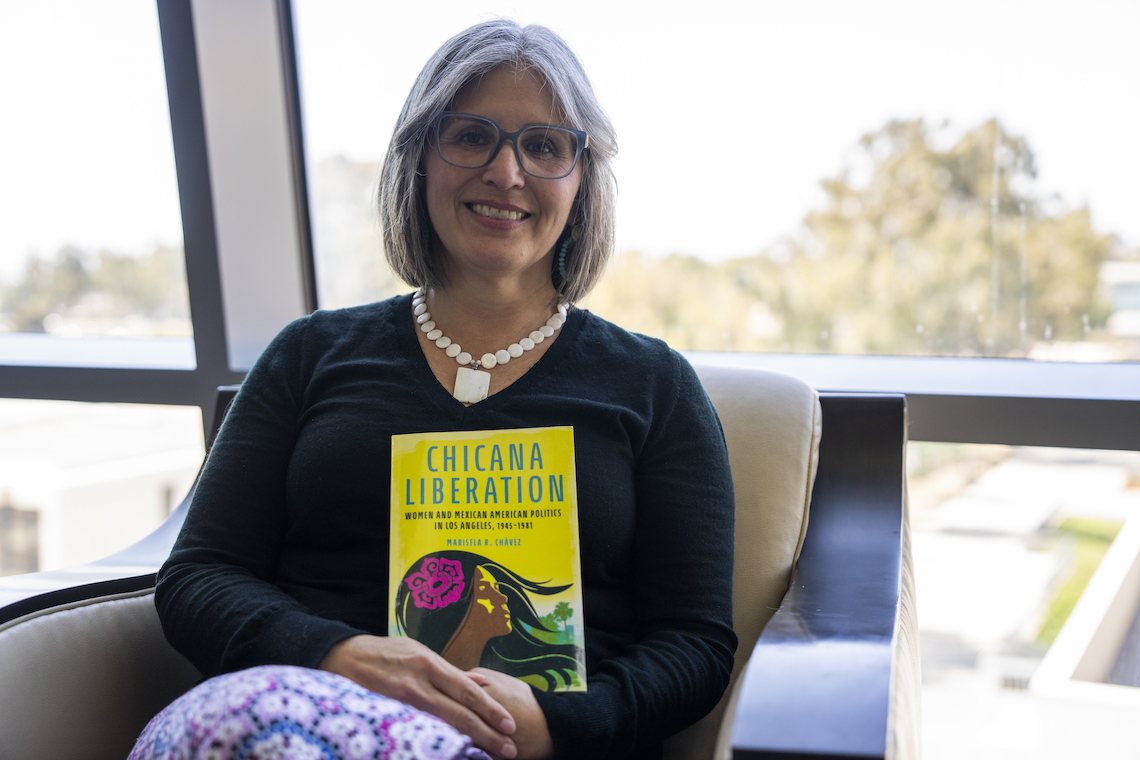

Chicana Liberation: Women and Mexican American Politics in Los Angeles, 1945-1981 (University of Illinois Press, April 2024), is Chávez’ new book, and the culmination of years of scholarship first inspired by her early experiences. While she was an American Studies undergraduate at Occidental College, Chávez had wanted to write about women in the Chicano movement. As a research novice, she found little of what she had witnessed as a child reflected in her academic sources.

“I knew there were lots of women in involved in this social movement. Why weren’t they there in the research?” she recalls. “It was a light bulb moment that led me to the path I’m on today.”

Keen to grow a nascent area of scholarship, Chávez had focused on women activists within Chicano organizations for both her master’s thesis and Ph.D. dissertation. She wanted to turn her research into a book once she joined the faculty at CSUDH, but stalled as time pressures from work and home kept her from writing. Chávez credits two historians—her uncle, Ernesto Chávez, and her mentor, Vicki Ruiz—with challenging her to continue.

“They told me that this story needed to be told,” Chávez says. “There was not much work out there on this topic and time period. They gave me the motivation to do one last push.”

Chávez’ book draws heavily from a trove of oral histories she collected over the years, as well as from interviews done by researchers at other institutions. She gained access to some interviewees through her personal connections, but also found people through her research. Alongside government documents, periodicals, and secondary literature, Chávez uses 20 personal accounts to shape the narrative of her book.

“Oral history is crucial because it’s another way to tell the story,” Chávez says. “In a sense, oral history is creating your own archive. It’s a way for those who have been marginalized to become part of the historical record.”

She also notes that often, “the research tells you where to go.” As Chávez investigated the establishment of Chicana women’s groups in the 1970s, her research revealed that many of the women involved had in fact been active in Los Angeles dating back to the 1940s. Her book charts what she calls a “bridging activism” between generations of women, and the impact it had on their movement.

“These older women had been old pros at politics, then brought along and mentored other groups of women within their organizations,” Chávez says. “That’s one of the most important parts—what happens when intergenerational knowledge and experiences come together.”

In addition to improving their own communities, the Chicana activists’ main priorities were to establish women’s economic autonomy and create educational opportunities. Some also questioned why they were sidelined by male activists, and were spurred on by wanting to forge their own path to liberation and self-determination.

“This isn’t the only story about women in the Chicano movement in L.A., but it’s part of that story,” Chávez says. “These women created their own space where they could build institutions, found periodicals, enact, engage, and become leaders. That’s the story I wanted to tell.”