Source: Los Angeles Times

IONE, Calif. — Decades ago as a little boy growing up in Santa Rosa, Luke Scott made a pledge to his mom that he would graduate from college one day.

Despite being sentenced to life in prison for murder without the possibility of parole in 1988, Scott kept his promise.

Scott, 60, earned his first of eight associate’s degrees from Coastline Community College in 2010 while at Salinas Valley State Prison. His mother kept a copy of his first degree hanging on the wall so she could boast of her son’s accomplishments. Twelve years later, long after his mother died in 2011, Scott went on to earn his bachelor’s degree in communications from Sacramento State while at Mule Creek State Prison.

He isn’t stopping there.

Scott is one of 33 students enrolled in what the state Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, or CDCR, has called a “groundbreaking” two-year master’s program in humanities, a collaboration with Cal State Dominguez Hills that launched in September.

“When I got into the bachelor’s program, it was like my ceiling was raised a little bit,” Scott said during an interview in a prison classroom days after courses began. “But when I got into the master’s program, my belief system in the ceiling went away.”

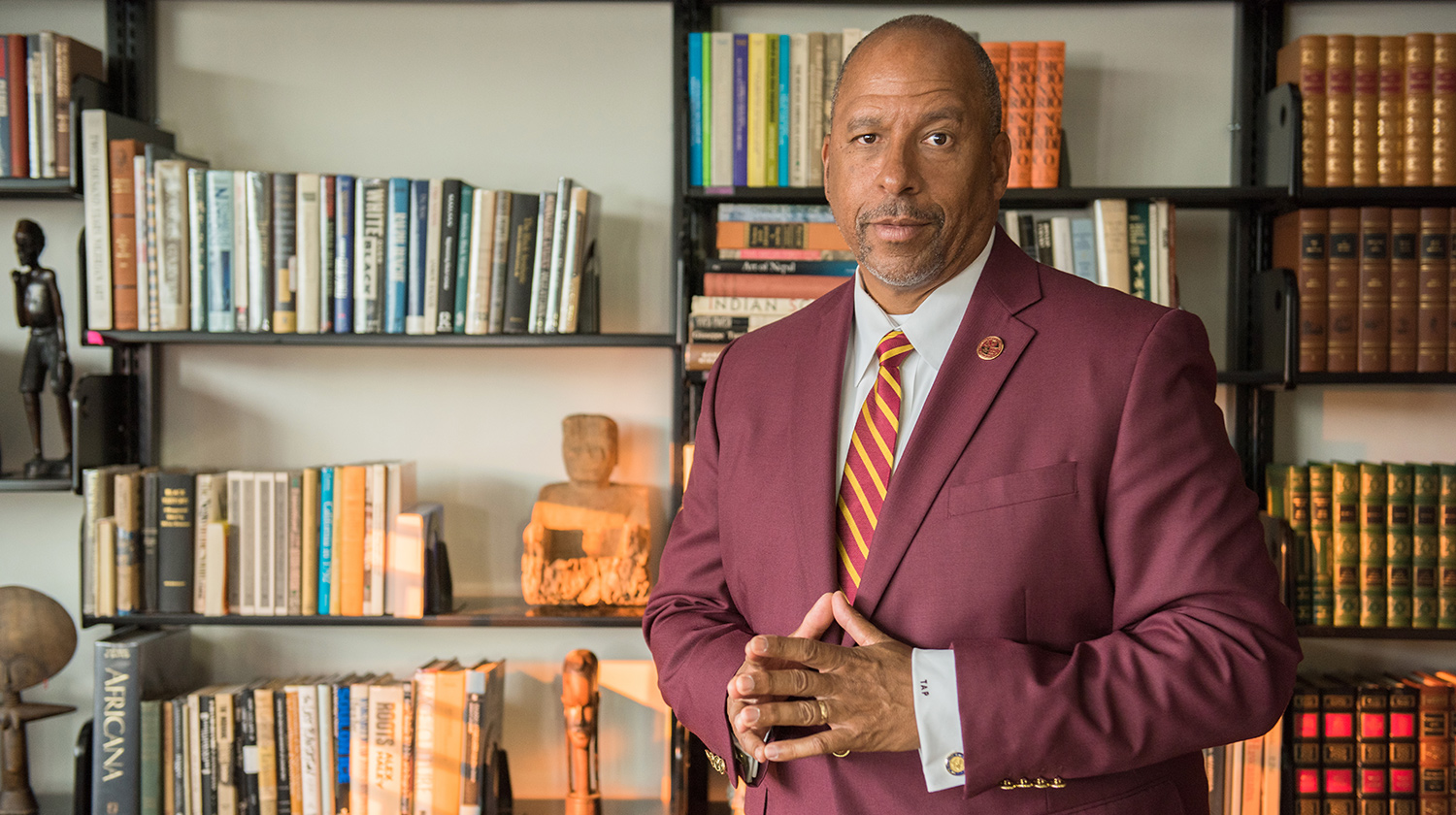

The program is a revamp of a similar humanities degree that dates back to 1974 but was discontinued in the last decade due to declining enrollment. After lobbying by incarcerated students interested in a master’s program, and with help from professor Matthew Luckett, who now serves as the program’s director, the CDCR partnered with Cal State Dominguez Hills to restore the degree program this fall.

Prison officials have touted the revitalized degree as a pioneering program that could serve as a national model, created exclusively for incarcerated students. While prisoners had the chance to earn a master’s degree before, it was typically at out-of-state colleges and students most often filed their work and communicated with professors by mail.

By contrast, the CDCR’s new program has students using state-issued laptops to take courses online through a portal where they can find and submit assignments and communicate with their professors. Luckett is working on plans for limited in-person instruction starting next year and making online discussion boards more interactive so students can discuss and debate their assignments.

Courses include an introduction to graduate humanities and graduate writing, the study of modern Nobel laureates and the history of American punishment and incarceration.

“I want us to be groundbreaking. Not just the first, but groundbreaking, and on the cutting edge,” Luckett said.

But that takes time.

The CDCR regulates inmates’ internet access and has robust safety measures in place, meaning in-person instruction and online debates between students and video livestreams are more difficult to get approved. Then there were the Wi-Fi issues and trouble in the first few weeks getting books and reading materials to students.

“We’re trying our best. This is very much a pilot program,” Luckett said. “We’re kind of feeling our way through the dark right now, trying to see what works and what doesn’t. It’s a process.”

Scott said he dedicates about seven or eight hours a day to his studies, on top of his typical rehabilitative programs and group therapy sessions. He looks for a quiet corner where he can put in his earplugs to drown out the prison noises, or he’ll use a near-empty classroom to do his work. He’s looking forward to an upcoming assignment that will have students reviewing each others’ work and submitting feedback, all anonymously and through the professor.

The program marks a next step in the decades-long effort nationally and in California to restore higher education opportunities in prisons, after a 1994 federal crime bill cut Pell Grant funding for incarcerated people and decimated college options for those behind bars. The federal government started lifting those restrictions in 2015, and full access to Pell Grants was only made available this July.

Over the last 10 years, California has shifted away from its tough-on-crime policies of the 1980s and ’90s and steadily passed legislation focusing more on rehabilitation and reducing recidivism. Those efforts included expanding education programs in partnership with community colleges and a handful of four-year universities in California prisons for thousands of incarcerated people. This year, more than 800 people received an associate’s degree, according to the CDCR, while another 17 earned their bachelor’s.

“We’ve come a long way,” said Shannon Swain, superintendent of the Office of Correctional Education. “There’s nothing more important … it’s about opportunity, and it’s about hope.”

Students can apply to the new master’s program if they already have a bachelor’s degree and graduated with a minimum 2.5 grade-point average. The degree costs roughly $10,500, which students or their families must pay. Certain financial aid is available through the Department of Rehabilitation with taxpayer funds and through the university. Cal State Dominguez Hills is additionally taking donations to cover tuition.

Luckett said all 31 of the incarcerated students in California have applied for and received financial aid, with their entire tuition and cost of books covered. Two students are out of state; one is on a private scholarship and the other is self-funding the program.

Romarilyn Ralston, executive director of Project Rebound, a college program for formerly incarcerated people, said education is one of the best ways to lower recidivism rates. Incarcerated people who participated in education programs had lower odds of returning to prison, according to a 2013 Rand Corp. study sponsored by the federal government.

Ralston, who started her college career while incarcerated, called the program a positive “next step” for those who serve long sentences or who earned a bachelor degree before entering prison.

But Ralston said it should be on the CDCR to cover the cost of tuition for students, not other state agencies, CSU or the students and their families. Ralston said the CDCR should use some of the $14 billion allocated in this year’s budget to invest in educational opportunities.

“They have a responsibility, a moral responsibility and a fiscal responsibility, to provide resources and services that help incarcerated people rebuild their lives,” Ralston said.

Decades ago, Darrell Dortell Williams remembers a meeting with his guidance counselor leading up to his graduation from Inglewood High School to talk about his future. With a 2.85 grade-point average, the counselor told him, Williams was “not college material.”

“I felt rejected,” Williams recalled during a video interview with a Times reporter from Chuckawalla Valley State Prison in Blythe. And from there, “I just made a lot of horrible decisions.”

Williams, 57, was sentenced to life without the possibility of parole for his wife’s murder in 1992. Since then, he’s earned four associate’s degrees from Coastline Community College and a bachelor’s in communications studies from Cal State Los Angeles in 2020.

He was about to graduate with his bachelor’s three years ago when he and other students realized there was no next step available. Williams started writing colleges asking if they would be interested in launching a master’s degree program for inmates — and received countless rejections.

But Luckett saw an opportunity with their interest, and urged the students to keep pushing for the program. The coalition wrote letters and launched surveys about what kind of classes they were interested in and, three years later, Cal State Dominguez Hills and the CDCR agreed to restart the degree program.

“A lot of us grew up in dysfunctional families, where there’s miscommunication, abuse, no communication at all,” Williams said. “Education kind of gives us that mainstream perspective we may not have gotten at home. It gives us a broader view of the world, of other cultures. It kind of gives us like a reset.”

Williams said education not only improves outcomes for students, but also strengthens relationships with prison staff and other incarcerated people on the yard, and inspires success stories from loved ones back home. He sees it as a way to improve public safety by creating job opportunities for those who will eventually go home, and as restitution for those who won’t.

“I just think that with 30 years of imprisonment, I’ve seen people change,” he said. “It can be because they fell in love. It can be just because of maturity and the natural stages of growing older. But I think overall, education has had the biggest impact on all of our lives.”

The broader goal is to ensure students have access to quality jobs after they are released from prison. But even for students like Williams and Scott who may never go home, the degree is beneficial, said Danny Murillo, co-founder and associate director of Underground Scholars at UC Berkeley, an organization that helps formerly incarcerated people earn college degrees.

“It’s, a lot of times, those that are not getting out that are the mentors, the cultural change agents in the prison,” Murillo said. “I think that having access to education, whether you are going to get out or not … it is important to give them that access. Because there are people that look up to them.”

Murrillo earned his GED and started his college journey while in solitary confinement at Pelican Bay State Prison in Crescent City. He transferred to community college after he was released and eventually graduated from UC Berkeley.

Murrillo said the new program is a good opportunity for incarcerated students, even while acknowledging room for improvement.

“Can we do better? Definitely,” he said, adding that every prison should have equal access to education programs, job fairs, extracurricular activities, networking, mentoring and other career-oriented efforts.

This semester’s students are only weeks into the program, but they’re already thinking of what they can do with their degrees.

Williams teaches his own classes in prison: on the Bible and character defects, political science and civic engagement and ways to deal with trauma. If he had the chance, he’d start his own nonprofit to facilitate restorative justice between those who have harmed and have been harmed, he said.

Scott also serves in mentorship roles at Mule Creek, and loves helping other students with their studies. He is working with an attorney to negotiate a shortened sentence based on mitigating factors in his case like trauma and abuse in his childhood, which could lead to an early release. Scott was convicted of robbery and strangling a man to death when he was in his 20s.

Scott has a business plan to renovate food trucks into mobile dental labs for those living on the streets. He has another idea, one that might make his mom proud.

“Wouldn’t it be awesome if I was to walk on campus one day and walk into my own office and say this is Associate Professor Scott’s office.”