Source: LAist

Like the Madrigals in the beginning of “Encanto,” Paty Lozano does not want to talk about Bruno.

Her one-year-old daughter watches the Disney animated film every day – sometimes more than once.

Everyone else in the family is sick of it. But for baby Soleil, the musical fantasy set in Colombia is a type of salve, so much so that it’s enabled Lozano to do the impossible: take a shower during the day.

Before jumping in for a quick rinse, Lozano drags Soleil’s high chair to the edge of the bathroom and straps her into place. Then, she puts another chair in front of the baby as an added safety measure and sets the iPad on her food tray. With Lin-Manuel Miranda’s smash hit before her, the giggling bundle of auburn curls sits enraptured, serene.

Carving out moments for self care is a constant in Lozano’s life. On top of her family duties, the mother of two is a student at Santa Monica College, and she’s still figuring out how to make that work.

Across the U.S., about one in five undergraduates are parents, according to the Institute for Women’s Policy Research. And the largest share of parenting students is enrolled in community colleges. Even so, surfacing the resources that schools have to offer can be an ongoing difficulty for students who are parents, if those resources exist.

Being Her Own Advocate

For Lozano, the biggest challenge is finding time to study.

She does this at night, after her husband comes home and her children fall asleep.

“Sometimes I don’t even realize it’s five in the morning, and I have to be up by seven,” she said. “I wake up tired, but I have to put that in the back of my mind. I just keep moving forward and hope that I can catch up on sleep the next day.”

Lozano is working on an associate’s degree in accounting. Her goal is to transfer to Cal State Northridge and become a certified public accountant. She wants “a 9-5 job,” the kind that will allow her to make the girls a nice breakfast before school, the kind that will enable her to pay for extracurricular activities with ease.

Her eldest child, Luna, is already in tap and ballet, but Lozano also wants her girls to play sports. “And all of that is expensive,” she said. But aside from providing for her family, Lozano has another reason for going to school: “I want to make myself proud,” she said.

Years ago, she actually was in a four-year university, at Cal State Long Beach. She was pre-med, and she felt lost.

“My mom always told me: ‘We need a doctor in the family.’ So I was, like, ‘Okay, that’ll be me,’” she said. “But I was an artsy person inside, and I wasn’t really into it. It was just something that I told myself I had to be.”

Things at home got complicated, and Lozano found herself on her own. She left Cal State Long Beach and tried her luck at art school. She also took math and chemistry courses at East Los Angeles College, all while working in the restaurant industry. With time, she took on managerial positions and discovered that she has a knack for working with numbers. Shortly before the pandemic began, she signed up for a statistics class at Santa Monica College.

“I went in, and I was the oldest one there,” she said. “I was sitting next to all these 19-year-olds, and all they talked about was getting straight A’s and transferring to these major schools. And I was in my 30s.”

At first, Lozano was too scared to speak up in class. But being a mom has given her courage. Just as she’s learned to advocate for her daughters, she’s learned to advocate for herself.

“Now I don’t care how stupid my question sounds,” she said, “I throw it in there. I’m not letting go this time.”

What Types Of Resources Do Learning Institutions Offer?

Paolo Velasco was about 10 years old when his mom went back to school. She was a single parent, so his grandmother watched him while she was in class.

His mom earned an associate’s degree in nursing at Los Angeles Valley College, a matter of pride for Velasco, who now directs UCLA’s Bruin Resource Center. Among other initiatives, it houses the university’s Students with Dependents Program.

“It really holds a special place for me,” said Velasco, who sees his mom reflected in the students he serves. “I see that same drive, that same determination.”

The program started over a decade ago, propelled by parenting students who wanted more institutional support. To be more inclusive, UCLA employs the term “students with dependents,” so as to make space for those who care for siblings, grandparents and other loved ones.

The program connects these students with resources on and off campus, including family housing and child care, which can be subsidized by the federal government. And thanks to a student referendum, UCLA’s Little Bruin Clubhouse offers evening youth programming for children up to age 12. This allows parenting students to attend evening classes and other school activities, like study groups and club meetings. The goal, said Velasco, is for parenting students to fully participate in student life.

Helping them build community is also top of mind for Velasco. Parenting students tend to be commuters, he noted, which limits their opportunities to mingle with peers on campus. Plus, because they represent about 2% of the university’s 44,000 undergraduate and graduate population, parenting students often tell him they feel invisible.

To help UCLA’s roughly 1,000 parenting students connect, the resource center employs them to drive programming. They also manage the program’s social media, where they share resources and opportunities to socialize, including student mixers; career development workshops; a support group for parents of toddlers; diaper giveaways; and “stress-less” cooking. On Instagram, parenting students showcase and celebrate their peers, often with extra love for transfer students.

Parenting students take pride in each others’ accomplishments, said Velasco, whose second son was born the day after he started his master’s program. “More than anyone, they recognize the sacrifices and just the strength that’s needed to get to a school like UCLA.”

To reach these students, UCLA partners with local community colleges to prepare prospective transfer students. Through summer, fall and year-long academic programs, university representatives guide them through the admissions process. According to Velasco, nearly 80% of undergraduate parenting students transfer from community colleges.

Of all events on campus, Velasco most looks forward to the parenting student graduation. The university, he said, supplies tiny caps and gowns for the students’ children. Then, they walk the stage together in front of their peers.

“There’s always someone crying in the background when there’s a keynote speaker,” said Velasco.“It’s never quiet, but it is beautiful.” In his view, the celebration embodies a two-generation approach to higher education, in which institutions create opportunity for families by addressing the needs of parenting students and their children.

Advocating For More

Zuleika Bravo was 24 when she decided to pursue an associate’s degree at Antelope Valley College, some 70 miles outside Los Angeles. At the time, her daughter was eight months old, and she had no intention of transferring to a four-year university.

At the college, Bravo majored in political science and worked hard to make good grades. She became a regular at office hours and often took her baby to campus. Soon, her professors began to take notice.

One of them, a UCLA graduate, referred her to the honors program. Then, he began nudging her to apply to his alma mater.

“I honestly don’t know what they saw in me,” said Bravo, who was pleasantly surprised by their encouragement. It wasn’t something she’d experienced from educators growing up.

“In high school, they didn’t really push us to go to college,” she said. “And so what I did is, I went straight to work.”

Bravo transferred to UCLA in three years, but despite being a strong student, she initially struggled to stay afloat.

Her new professors, she said, were less willing to accommodate scheduling conflicts than her community college professors had been. Plus, as a first generation college student, she didn’t know there were resources to help pay for things like family housing and child care.

Connecting with other parenting students helped Bravo get informed and stay motivated. “Being first gen and a parent, like, we’re really good at researching,” she said. “And we share that information to help each other.”

The parenting students also formed study groups, which enabled them to get their work done while their children played. Toward the end of their undergraduate careers, they even helped each other apply to graduate school.

“It was a community that understood what I was going through,” said Bravo. “They were always, like, ‘Hey, if you need to study tonight, I’ll watch your daughter. You go ahead and you do what you need to do.’”

Today, Bravo is a graduate student at UCLA’s Department of Higher Education and Organizational Change. She’s also an intern at the Students with Dependents Program, all in an effort to help make education more accessible for parenting students.

At the university, change is very student-driven, she said. If UCLA’s parenting students now have priority enrollment, it’s because former students advocated for it. Next up, she’d like to see the university adopt a reduced course load option, like at UC Berkeley. This would enable students with family responsibilities to enroll part time without affecting their financial aid.

Securing Housing, An Added Layer Of Difficulty

Like Bravo, Yvonne Chamberlain Marquez started her higher education journey without planning on transferring. She began at Citrus College in Glendora, shortly after graduating from high school in 2003.

Marquez was on her own and found it tough to pay for school on top of her living expenses. She also didn’t know how to secure financial aid. And so, she focused on work. But when her first daughter was born a decade later, she wanted more.

“I was a single parent,” said Marquez. “I had a diploma and I had some retail experience, but there just was no feasible way that I was going to be able to raise my daughter with any of the jobs that were available to me.” She enrolled at Mt. San Antonio College in Walnut and figured she’d get a paralegal certificate.

But then she met Holly Cannon, a professor in the English department. During class one day, Cannon had her students rewrite some sentences. Then she collected them and read them aloud.

“She got to mine and said: ‘This is one of the best ones I’ve ever read,’” said Marquez. She wasn’t used to receiving compliments. The feeling sparked something inside her.

Her counselors were also her champions. One of them told her about a scholarship and “would not leave me alone until I submitted it,” said Marquez. Then she discovered something called public history, which takes the discipline beyond the confines of a traditional classroom to public spaces. Marquez fell in love.

She got the scholarship she was badgered into applying for – called “Live Your Dream” – and figured she should do as instructed. She applied to four UCs and four Cal States and was admitted to all. UC Riverside, which has a strong public history department, offered her a prestigious regents scholarship and guaranteed housing. Marquez accepted with excitement. She thought she was set.

“But when I started communicating with the university,” she said, “they were, like, ‘Yeah, we have family housing, but there’s a two year waitlist.’”

In a state of desperation, Marquez tried to secure housing off campus. All available apartments required good credit scores and incomes three times what she made. She reached out to the university again, reminding representatives that her acceptance letter said housing was guaranteed. In turn, the campus explained that it referred to students who could live in single honors dorms. By then, Marquez’s daughter was in kindergarten. She found temporary housing in a nearby city and commuted back and forth. To stay afloat, she dropped some of her classes.

“It didn’t matter how good of a student I was, or how much I was going to push through,” she said. “I couldn’t pull time out of thin air.”

Marquez persisted. She wrote to Brian Haynes, Vice Chancellor of Student Affairs, and let him in on the details of her housing saga. Soon after, the university found a spot for her in family housing.

Marquez, who will graduate this June, still gets upset when recounting this experience. Since then, she’s become an active member of R’Kids, an organization led by parenting students at UC Riverside. Like its counterpart at UCLA, the group hosts mixers and family-friendly events. It also uses social media to share information about opportunities like paid internships. In the past, members have worked to secure lactation rooms for nursing mothers. They’ve also advocated for campus shops to take EBT, the public benefit program that allows recipients to purchase food using a government-issued card.

At UC Riverside, parenting students have access to child care and a free food pantry. Scotty Cubs and Parents, another peer support group, also provides a space to talk about school, home and parenthood. Still, Marquez maintains that the campus has room for improvement.

She’s part of a Student Parent Task Force that presented recommendations to Haynes earlier this year. For her, family housing must be a priority.

Haynes welcomed the recommendations and noted that UC Riverside has 136 units for family housing. The university, he added, currently has 26,847 undergraduate and graduate students. Self-reported data indicates that 2% of them are students with dependents. The university is also working to expand its graduate student population, so housing – both on and off campus – is part of the university’s long-term plan, he said.

A Moral Obligation

At Cal State Channel Islands, students in Maricela Becerra’s courses will find a parenting/caregiving policy on the syllabus. In a brief statement, she lets parenting students know that they can approach her if they need help.

“If they need extra time because their dependents get sick or their schedule changes or things like that, they’re more than welcome to ask me,” said Becerra, an assistant professor of Spanish and Latin American literature and culture. Children are always welcome in her classroom, she added, both virtually and in person.

Becerra had her first child as an undergrad at Cal State Long Beach and her second child while earning a doctorate at UCLA. “I’ve been through most of my higher education journey as a mom, and I never felt supported or seen, so I want to be that support now,” she said.

While earning her master’s at Cal State Long Beach, she went to work as a teaching assistant after staying up all night with her child in the hospital. At the time, she said, she didn’t know she could call out. By the time she got to UCLA, Becerra was more vocal.

The campus had a few lactation rooms when she was a student, “but you had to go inside the restroom and there was a little room on the side to pump or breastfeed, and you could smell everything. It was disgusting,” she said. In 2016, she and other members of Mothers of Color in Academia petitioned the university to provide more and improved lactation rooms on campus, along with increased access to child care. (According to the petition, parenting students were on “1.5 to 3-year long waitlists for subsidized care.”)

In retrospect, Becerra feels a sense of pride. “But, honestly, I don’t think we should’ve had to use our very limited time to ask for basic things,” she said.

Resources for parenting students vary widely across California’s public universities and colleges. This, in part, is due to differences in student demographics. A University of California report published in 2019, for instance, found that UC Riverside had the largest percentage of undergraduate parenting students (1.7%), while UC Irvine had the largest percentage of graduate parenting students (16%).

At Cal State Dominguez Hills, the Women’s Resource Center provides social programming for parenting students, including peer support groups. The university also has four lactation rooms and a daycare for children ages 2 through 5. Parenting students pay $30 a day for these services, which “is way less than what they would get off campus,” said Dean of Students Matthew Smith. The Infant Toddler Development Center provides care for younger children.

Cal State Dominguez Hills, he added, is unlike most four-year institutions, whose undergraduate students tend to be 18-22 years old and live on campus. Most of the students Smith serves are commuters, their median age is 25, and the majority of them are transfer students who identify as female. The university, however, is not sure how many of them have dependents.

“We need to get a better pulse of the need,” said Smith. To this end, the university will soon launch a campus-wide assessment. He anticipates it will reveal the need to expand access to campus child care.

“Even if there’s only a handful of parenting students that matriculate through each year, we have a moral obligation to meet their needs,” said Smith.

Joanna Hernandez, the Programs Director for the Transfer Student Center and Assistant Director for Student Success Initiatives at UC Irvine, keeps close tabs on parenting students at her campus, where most undergraduates have also transferred from community college.

“I check in on them on a regular basis,” she said. “I’ll also check grades and follow up with students who might have fallen below a 2.0 GPA. I tell them: ‘Hey, how are you? I noticed that you had a rough quarter. What do you have going on? What can I do to help you?’”

“Sometimes it’s just connecting them to campus resources. Sometimes they have more complex issues, so I connect them to a social worker and agencies outside of UCI. But a lot of the times they just need somebody to talk to. They’re balancing so much,” she added, “and they shouldn’t have to do it alone.”

Making Success Systemic

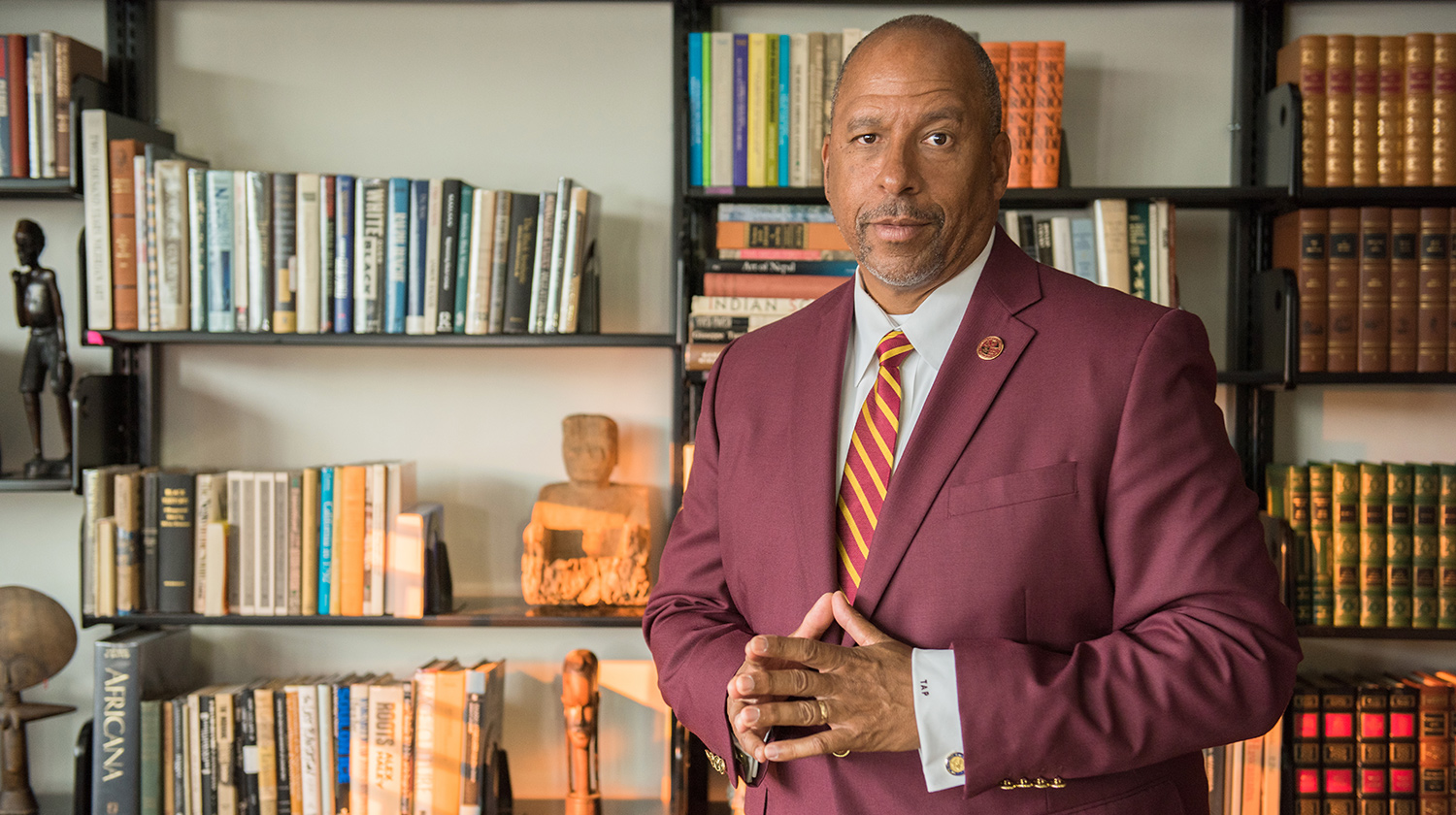

Much like Lozano, Bravo and Marquez, Mike Muñoz began his higher ed journey as a father in the California Community College system with no intention of pursuing a master’s degree, much less a doctorate.

He credits Ronaldo Sanabria, his counselor at Fullerton College, with changing the course of his life.

“It was the first time that I met anyone who was Latino with an advanced degree,” said Muñoz, who now serves as Superintendent-President of the Long Beach Community College District. “I remember seeing it on his office wall.”

Sanabria challenged “my perceptions and norms around what masculinity looked like,” Muñoz added. “I felt like I could be vulnerable with him and talk about some of the things that I had been through, some of the trauma in my younger years . . . And at the time, I was a single parent. I was dealing with coming out. I was dealing with housing and food insecurity – there was a lot happening in my life.”

Sanabria connected Muñoz with resources and encouraged him to open up to new possibilities.

“He told me, ‘You need to go on the Northern California College Tour. Go see Berkeley and Stanford and Sacramento State’ and all these schools and things that just did not seem in the realm of possibility,” said Muñoz. “He illuminated a path for me, and he helped me develop the skills to be able to manage my life.”

Looking back on this experience, Muñoz remains grateful. Still, he wonders what would have become of him had he not met Sanabria.

“As educators, what are we doing to ensure that we take out this random happenstance factor of, you know, you made it because you happen to cross someone’s desk?” he said.

“I want students to make it because our systems and structures are strong, so that you can move through this system in a way that’s going to uplift you, support you, inform you and get you to where you want to be. Because I always think about the student that wasn’t as lucky as I was. What happens to them and their dreams?”