Source: LAist

The Student Health Center at Cal State Dominguez Hills saw use of its services plummet after the COVID-19 pandemic hit. That’s not a surprise. Students didn’t set foot on campus for months at a time.

“During the COVID years, we were down significantly, seeing… 1,200 [to]1,100,” students, said Susan Flaming Yeats, who directs CSUDH’s Student Health Center. Before the pandemic the center served a high of 1,241 students in Sept. 2019.

To turn things around, last year the center’s staff made it a goal to increase the number of students served by 7%. By the end of the academic year they’d more than doubled that goal. So far this semester the center has served 1,402 students, not even half-way through the academic year.

“We’ve been really doing a lot of outreach,” she said, and students are coming forward to ask for a wide variety of health services.

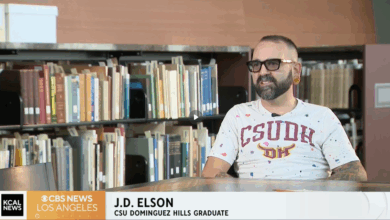

So as California State University undergoes budget cuts, this campus is leaning on a peer advisor model to help get essential health services to students. This academic year CSUDH has hired a dozen “peer ambassadors” so far in its effort to help students tap into affordable health care provided on campus.

The tactic has worked at other campuses, too, helping bring awareness to services many students don’t know exist, like medication abortion.

What have the ambassadors done so far?

Nearly two months into the school year, the peer ambassadors at CSUDH have carried out five tabling events along busy school walkways to give students information about self care, menstrual health and other well-being services. Two more tabling events planned this month will disseminate information about mindfulness and sexual health.

“I think [the students] just really are back in business,” Flaming Yeats said.

The most in-demand services include the on-campus pharmacy, X-ray services, and mental health counseling. And new this year: gender affirming hormone therapy, which helps students transition gender.

Students pay a $285 health services fee for the academic year. Visits to the health center are free and prescriptions are discounted.

“This is essentially the cheapest health care you’re going to have in your life,” Flaming Yeats said.

But to hear that, students need to come into contact with the student health center and their employees and because students are often served by outside doctors, clinics, and hospitals, that doesn’t happen as often as it should.

“The peer kind of advocate model might be really effective, and I think it’s important that student health has a role in that,” said Dylan Roby, a professor of health, society, and behavior at UC Irvine.

The challenge, Roby said, is that health care is provided to college students in different locations from residence halls to urgent care and hospitals, and student health centers could be good places to follow up with students because the centers are on campus.

What about at other CSU campuses?

Better student access could also mean better student service.

A 2014 audit found that the student health centers met a lot of their objectives. It identified a weakness, too: a lack of oversight by the CSU chancellor’s office, nor even a definition of oversight. In response, the Chancellor’s office created a once-every-other-year review process of the student health centers.

But the audit did not set out to measure whether the student health centers adequately served student health needs.

“We haven’t done a systemwide benchmarking report for some time,” said Flaming Yeats via email.

A report is in the works and should be done in the next few months, she said, to provide information about how well student health centers serve students.