In Notes from the Field, Ken Seligson, assistant professor of Anthropology, writes about his study of Pre-Colonial communities in the Puuc, an area of Yucatán.Posts run chronologically, with the most recent on top.

Quick links to previous posts:

July 5: Saludos from Yucatan, Mexico

July 7: Mapping Ancient May Sites

July 10: The Not-So-Mysterious Ancient Maya

July 12, 2021: Looking Ahead to Summer 2022

This summer’s preliminary field season has been a huge success. We confirmed the existence of the major archaeological features at the two small study sites, and identified several others that were not visible in the lidar imagery. One of the most exciting finds, in addition to the standing architecture, was the existence of a substantial aguada, or human-made reservoir, at each site. This helps address the question of how the communities survived the six-month-long dry season each year.

Most importantly, the research this week has laid the groundwork for more extensive field seasons in the summers to come. We now know exactly where we will want to establish our excavation grids to increase the potential that we will recover artifacts that can tell us about the past lifeways of the people who lived there.

Both sites were inhabited during times of social and climatic destabilization. Our project will investigate whether smaller-scale communities were more resilient than their larger neighbors, and perhaps continued on after the urban centers were abandoned. We will investigate such potential adapt strategies as communal pooling of resources and maintaining a more inclusive, egalitarian spirit.

The plan is to bring at least three CSUDH undergraduate students down with me next summer to help with the fieldwork. As research assistants, they will help finish mapping the two sites and record the artifacts we uncover during excavations. This is, of course, presuming that the public health conditions will have improved in the U.S. and Mexico by then. Any interested students should plan to enroll in my ANT 333: Ancient Peoples of Mexico course this spring, which will be focusing on the Classic Maya civilization.

My colleagues and I have built up our research compound, MPARC, over the past decade to include all the resources that an archaeological project could ever want, plus a few additional amenities to keep us comfortable during the long field season. The compound is within an hour’s drive of dozens of Pre-Colonial and Colonial-era archaeological sites, and only a few hours from the Yucatecan coast. Students will get first-hand experiences with archaeological and anthropological research, working closely with my colleagues and me, as well as our collaborators from the smaller towns in the Puuc. They might even pick up a little Yucatec Mayan.

In the meantime, I will work with colleagues across campus to explore the potential for additional research projects based out of our field compound on topics related to public health, business administration, biology, environmental science, and more.

That’s all for now. I (and the student research assistants) look forward to sharing updates from the field with you again next year!

July 10, 2021: The Not-So-Mysterious Ancient Maya

As far as ancient civilizations go, the Classic Maya get a lot of attention from popular media outlets. Photos of huge pyramids swallowed by dense forests, beautiful painted ceramics, and intricate hieroglyphic texts eroding from carved monuments all make for a tantalizing narrative about a “lost” or “mysterious” civilization. The truth, however, is that after over 100 years of archaeology in the Maya lowlands, we actually know a lot about Classic Maya history and culture. There are still many questions that remain unanswered, and there are still hundreds of ancient sites that have yet to be investigated, but the ancient Maya are really not so mysterious to us at this point.

The Classic Maya civilization that existed in Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, Honduras, and El Salvador between 150−950 CE receives much of the attention in the popular literature, but it was preceded by thousands of years of cultural development. We know, for instance, that foraging groups were already crisscrossing the Yucatán peninsula at least as early as 13,000 years ago, but likely even earlier than that. Farmers started settling down into small villages around 5,000 years ago. They grew a wide range of crops such as maize, beans, squash, manioc, and arrowroot, and tended an even wider range of fruit trees, including cacao, papaya, guava, palms, and pitaya (yes, dragonfruit is actually a cactus species native to the Americas)!

The Preclassic Period, which began about 4,000 years ago, saw the rise of semi-divine rulers and the construction of some of the largest sites with the most gigantic pyramids ever built in the Maya area. Many cultural traits that would come to define the later Classic Period and continue up through the present in many communities across eastern Mesoamerica began to crystallize during the Preclassic at sites like Aguada Fénix in Mexico and El Mirador in northern Guatemala.

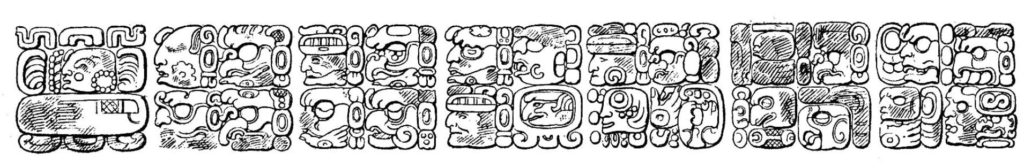

After a socio-political downturn around 100 CE that saw many of the larger Preclassic sites abandoned, populations began to grow again. This next period of growth and cultural florescence, what we know today as the Classic Period, was characterized by hundreds of independent city-states, each with their own god-kings and queens. The Classic Maya communities shared a common language, architectural aesthetic, and other cultural traits. Since the 1980s, researchers have deciphered most of the Classic Maya hieroglyphic script, allowing us to read the first-hand histories of the Maya city-states in a similar fashion to how we can read Classical Roman or Greek history. We know about marriage alliances, battles fought, and the deeds of individual rulers.

It is perhaps unsurprising that what tends to fascinate people most about the Classic Maya civilization is the fact that it eventually broke down, and did so relatively rapidly in some sub-regions. Researchers have investigated the possible cause of the massive societal destabilization and reorganization that occurred roughly between 750−1000 CE, and we now know a lot about what was happening. There were many overlapping factors at play that included increasing warfare, civil unrest within individual kingdoms, environmental overexploitation, and climate change in the form of mega-droughts.

The fact that the story of the end of the Classic Period is so complicated, with various combinations of factors affecting different communities at different rates, often leads popular outlets to opt for the much easier phrase, “the collapse of the Classic Maya civilization remains a mystery.” Too often, this feeds into broader statements suggesting the Maya people and culture altogether disappeared around that time – so not true! There are more than seven million ethnically Maya people alive and well in eastern Mesoamerica, continuing cultural practices that began thousands of years ago.

The breakdown and re-organization of Maya society near the end of the first millennium CE is really just a blip in a much longer cultural trajectory that includes several ups and downs. Having developed a complex civilization in a challenging tropical forest environment and survived several climatic downturns, as well as the Spanish invasion in the 1500s, the story of the Maya should really be one of sustainability and resilience, not of collapse.

Next summer, CSUDH undergraduates will help uncover additional evidence of ancient Maya sustainable environmental practices as we begin our full-scale investigation of two small, rural communities in the Puuc.

July 7, 2021: Mapping Ancient Maya Sites

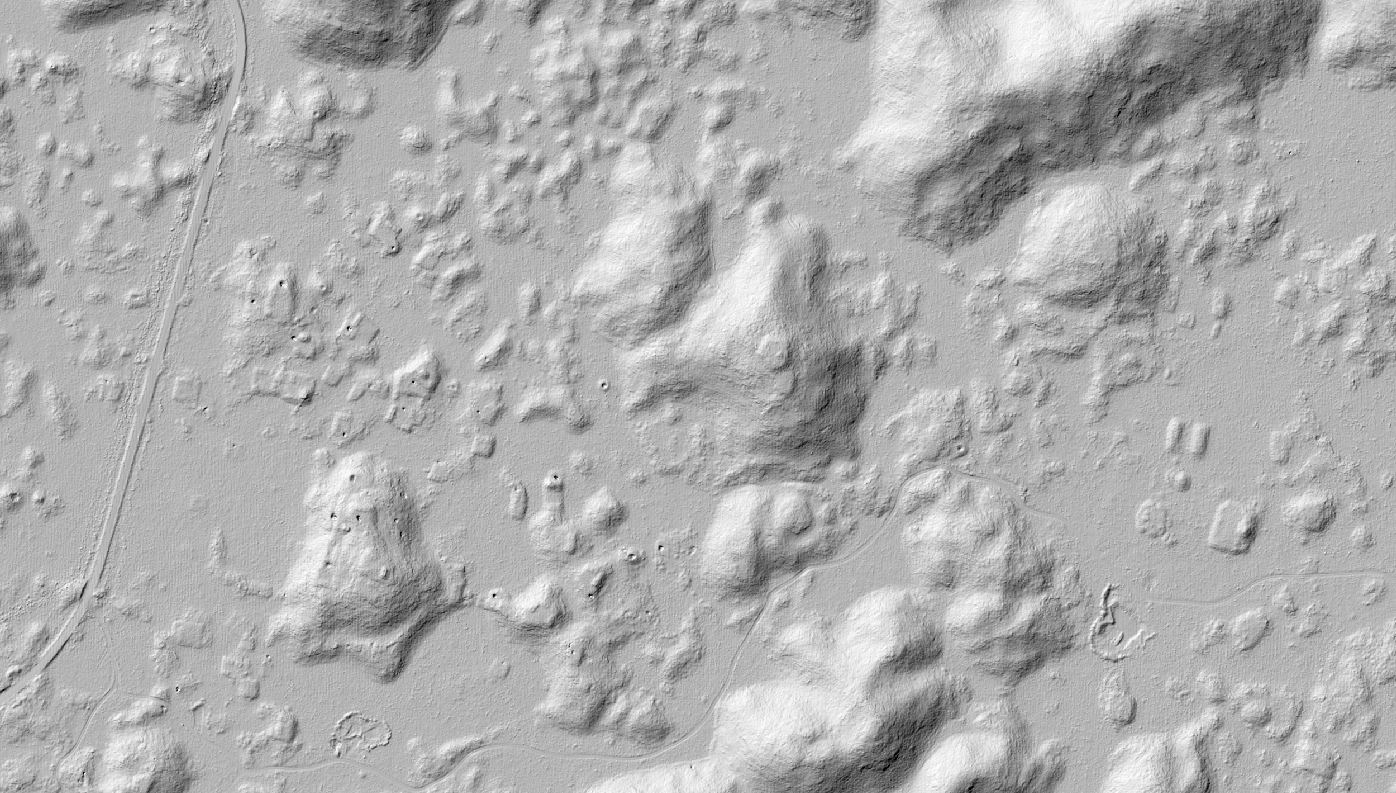

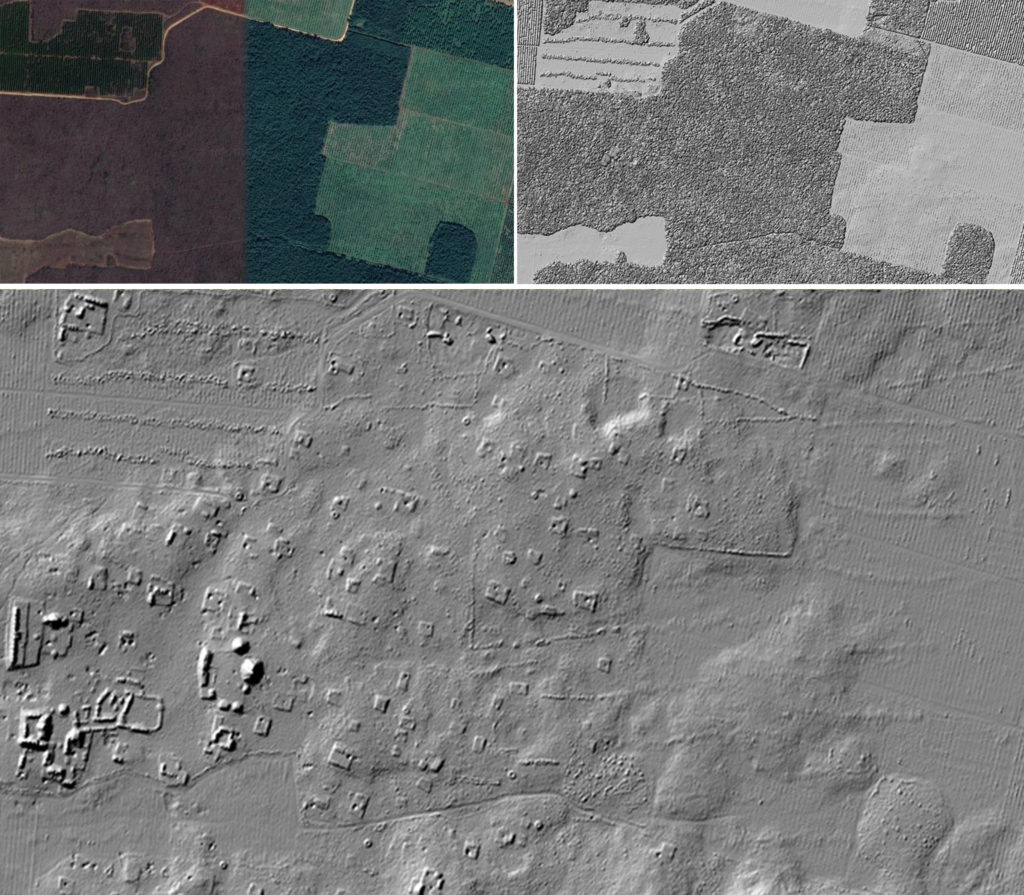

This field season, my collaborators and I are creating preliminary maps of the new research sites, which were first identified using lidar (Light Detection and Ranging) airborne laser scanning technology. The lidar instrument is attached to a low-flying plane that zigzags back and forth over the jungle, emitting about 150,000 laser points per second. These points bounce off the surface below and back up to the instrument’s sensor, providing a vertical distance measurement.

In the densely forested Puuc Region, more than 99.9 percent of those laser points bounce off the tops of the trees, with less than 0.1 percent making it all the way to the ground. However, by stitching together those points that do make it to the forest floor, we can create a digital elevation model that includes archaeological features. Archaeologists can use lidar scanning technology to virtually pull back the forest canopy to reveal the ancient sites below!

However, lidar does not capture everything – it is merely the first step in the site mapping process. The next step is what we are doing right now – visiting the sites in person to confirm the existence of structures and record smaller features that are less likely to show up in the digital elevation models. Often, we find carved stones and ceramics on the surface that are likewise not visible in the lidar-based images.

I use a handheld GPS unit to record points for all of the archaeological features. At the end of the day, I upload the points to the ArcGIS program on my computer to perform more advanced geospatial analyses. Another key component of preliminary mapping is drawing detailed sketch maps. The data collected this summer will be critical for securing funding for the longer-term project that we plan to begin next summer.

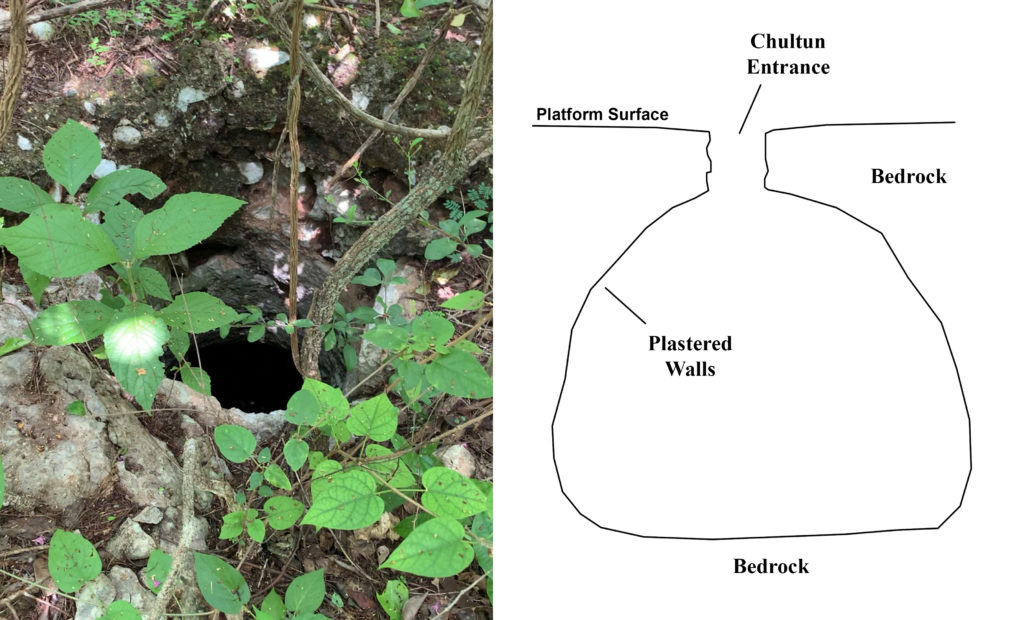

Already this week, my local collaborators and I have identified a few smaller structures that were not visible in the lidar, as well as a chultún (a subterranean water tank). One of the structures that was clearly visible as a mound in the lidar imagery turned out to have a few standing walls! It is pretty incredible that despite the dense jungle growth, this 1,200-year-old structure remains partly intact. It is a testament to the ingenuity of the people who created it.

The chultún is part of an elaborate water management system that Pre-Colonial residents of the Puuc developed to survive through the dry season. Unlike many other regions of the Maya area, the Puuc has no surface water. Communities relied completely on rainfall for all of their water needs. They created huge communal reservoirs and excavated chultúns into residential platforms. Excavators would dig through the limestone bedrock to create a large chamber and then plastered the walls with watertight stucco. The platform surface was also paved with stucco and slightly inclined towards the cistern opening. Whenever it rained, the water would funnel into the chultún opening and thus the entire residential group served as a water storage and capture mechanism. Some chultúns could hold over 20,000 gallons!

We will be checking out some of the other residential platforms on the outskirts of this 1200-year-old agricultural community tomorrow, and then visiting an even smaller site just to the east on Friday. That site, which will also be included in our larger project next year, has an ancient ballcourt for playing the Mesomerican ballgame and likely dates to over 2500 years ago!

(For more information about lidar in the Maya area, check out Lost World of the Maya and keep your eyes peeled for a brief cameo).

July 5, 2021: Saludos from Yucatan, Mexico!

My name is Ken Seligson, and I am an assistant professor in the Anthropology Department. I am an archaeologist focusing on human-environment relationships among Pre-Colonial Maya communities in the northern Yucatán Peninsula. During the school year, I teach courses on Mesoamerican cultures (past and present), ancient civilizations from around the world, and general anthropology.

This week, I am down at my research compound in the town of Oxkutzcab, Yucatán, to conduct preliminary research at my new field site. While here, I wanted to write a couple of short blog posts as a kind of “preview” to share a little bit about the work that CSUDH students and scholars will be doing down here in coming summers.

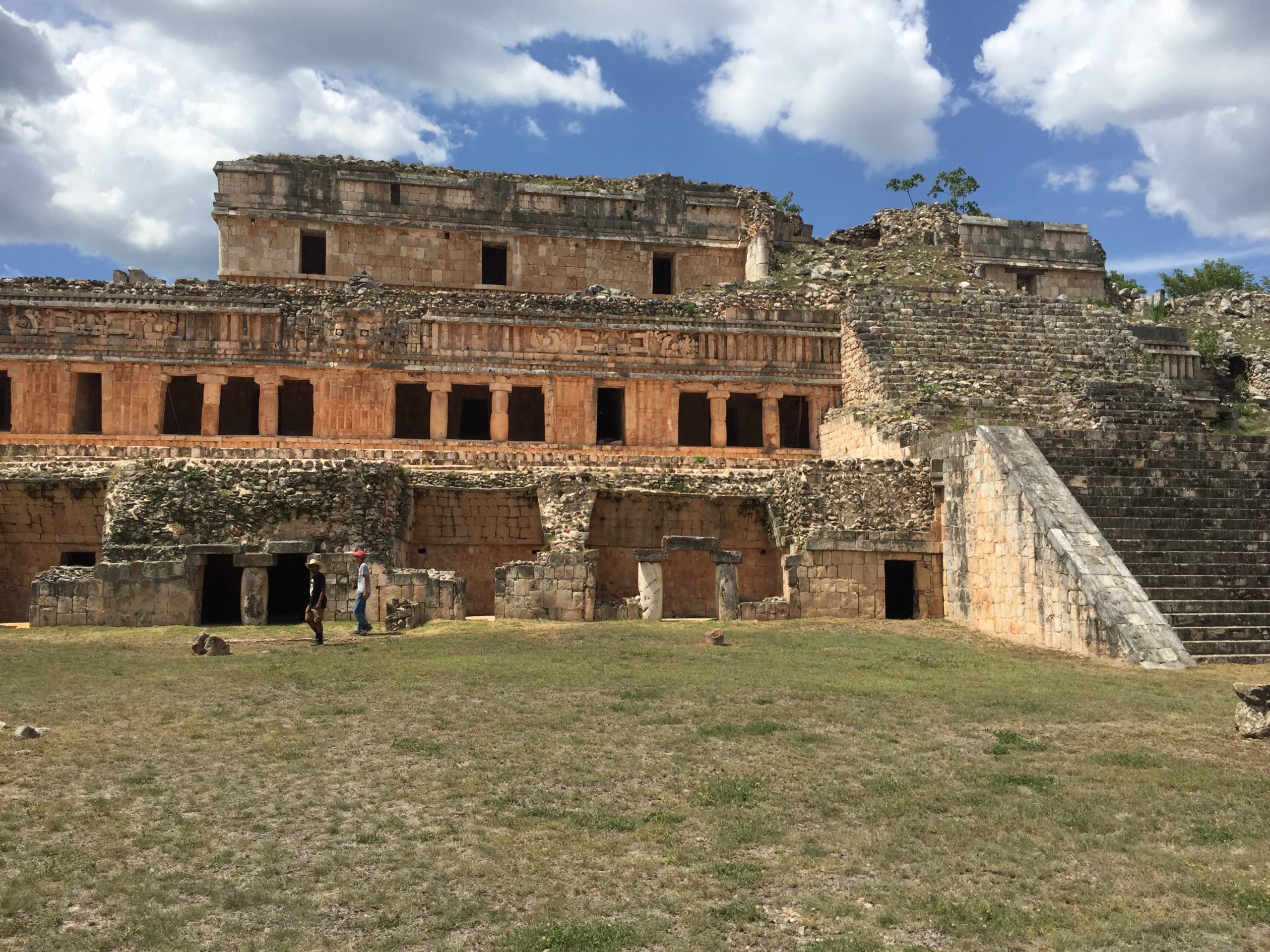

Oxkutzcab (pronounced Ohsh-kootz-kahb) means “three-turkey-honey” in Yucatec Mayan – it is a euphemism for “marketplace” and references the large market at the center of town. It is one of several modern towns situated right at the edge of an elevated, hilly region called the Puuc (Pook) – Yucatec for “hill.” The Puuc region is chock-full of archaeological sites that date back over 1,000 years and include some of the finest examples of Pre-Colonial Maya architecture. Many buildings are still standing amidst the lush, green forests.

While in Ox, I live and work with colleagues from Mexico and other U.S.-based institutions at the Millsaps Puuc Archaeological Research Compound (MPARC). The facility has expanded bit by bit over the past decade and is almost embarrassingly luxurious as far as archaeological field accommodations go. It now includes four casitas (dormitories) with hot water, a full research laboratory, a full kitchen and nice eating area, and a large storage facility. There is high-speed Wi-Fi accessible throughout the compound.

The comfortable lodgings make a grueling two-month archaeological field season that much more enjoyable. Most days, we are off in the dense, humid forest, mapping ancient sites and carefully recovering data to help us piece together the lifeways of Pre-Colonial communities in the Puuc. When the heat index regularly rises above 100 degrees by 1pm in June and July, it is nice to be able to come back to MPARC and relax a little in the afternoon.

This week, I am teaming up with a crew of local collaborators from the small village of Kancab (“red-earth” – an homage to the ubiquitous red clay soil of the Puuc) to explore the field site that I will begin excavating next summer with the help of CSUDH students. My colleagues and I recently identified the site using lidar airborne laser scanning technology (more about lidar in my next post). This week’s visit will mark the first visit to the site by an archaeological field crew, a necessary step before we can begin an intensive investigation of the site next year.

I am excited to share more details and photos from this week’s preliminary fieldwork, as well as the plans for upcoming summers, in my next posts!