History

-

Archive

L.A. Times: In 2024, Books by and about Southern California Latinas Shined

Professor Marisela Chávez’ book, Chicana Liberation: Women and Mexican American Politics in Los Angeles, 1945-1981, was reviewed by columnist Gustavo…

-

Archive

Los Angeles Free Press Collection Now Available at CSUDH’s Gerth Archives

An archivist works to sort and catalog Los Angeles Free Press Collection materials. The Art Kunkin Los Angeles Free Press Collection is now available…

-

Archive

Community History-Making at Forefront of Archives Event

University archivist Amalia Medina Castañeda History isn’t bound by the walls of a university, library, or museum. It can be…

-

Archive

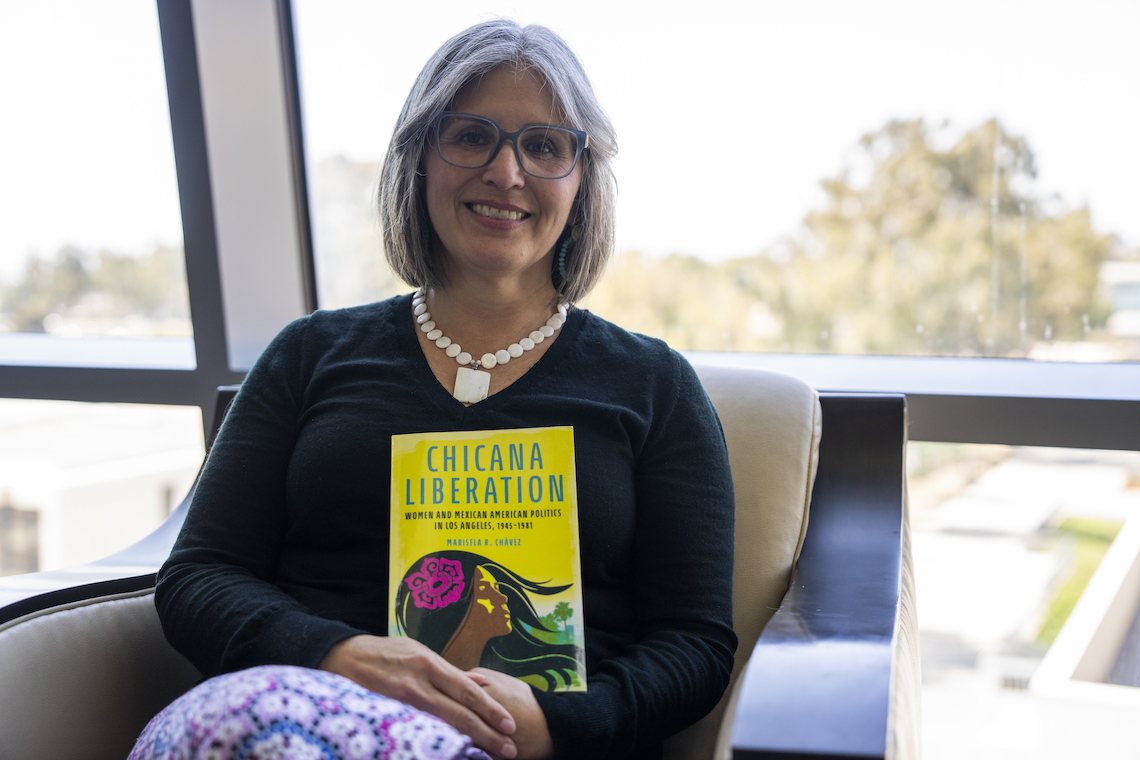

Unveiling Untold Stories: Professor’s New Book Explores Chicana Liberation and Mexican American Women’s Activism in L.A.

Growing up in East Los Angeles in the 1970s, Marisela Chávez had a front-row seat to the grassroots activism of…

-

Archive

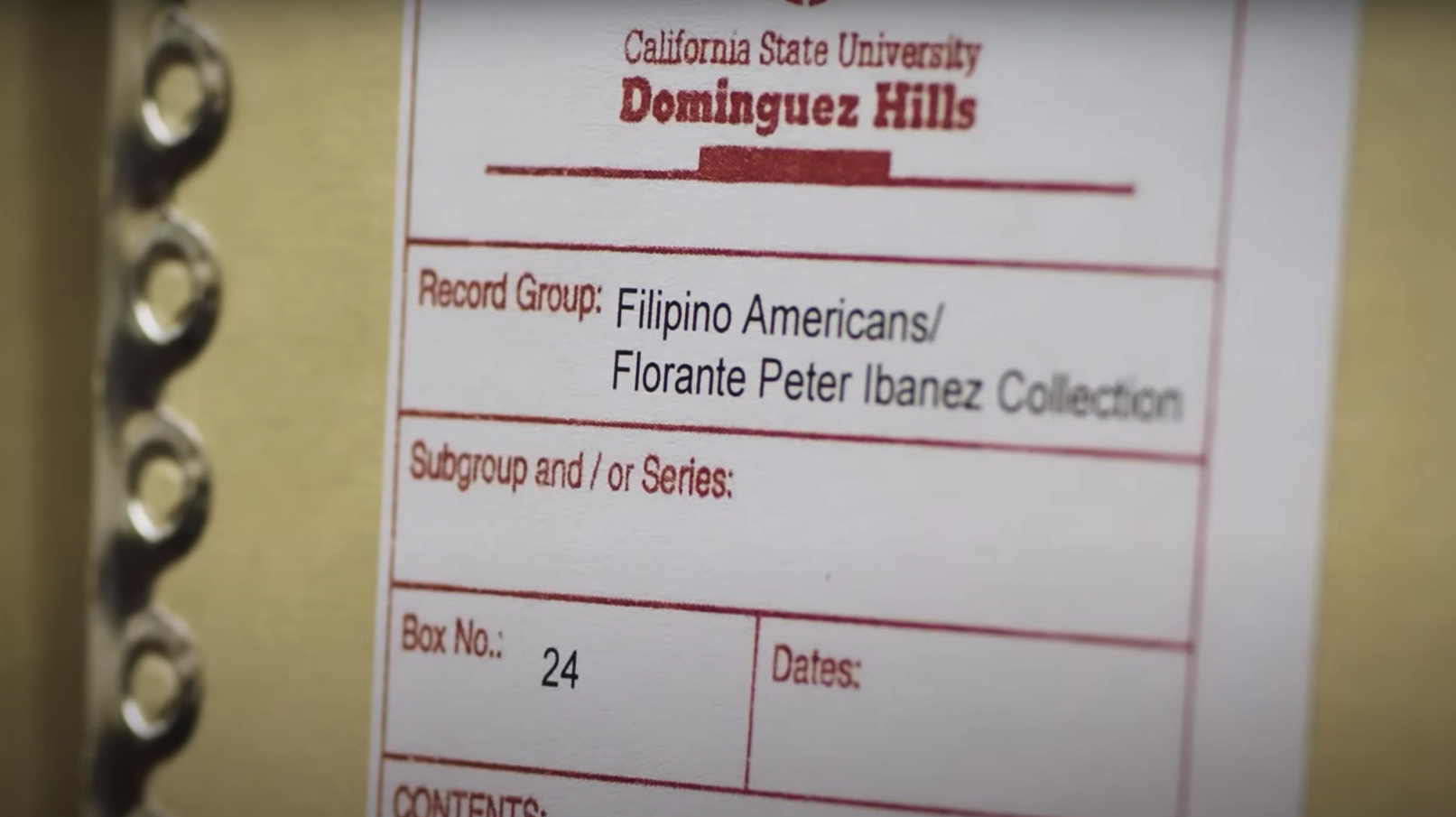

KCET: Historic Filipinotown

Source: KCET’s “Lost LA” (YouTube) In this episode, host Nathan Masters explores the yo-yo’s surprising origin story, tours L.A.’s Historic…