Source: The Art Newspaper

California’s water crisis is the backdrop to several hard-hitting shows, which will open across the state in September

Art made about water in Los Angeles might be its own genre considering how often and with what sincere depth artists consider the role of the river in the Los Angeles landscape and its infrastructure.

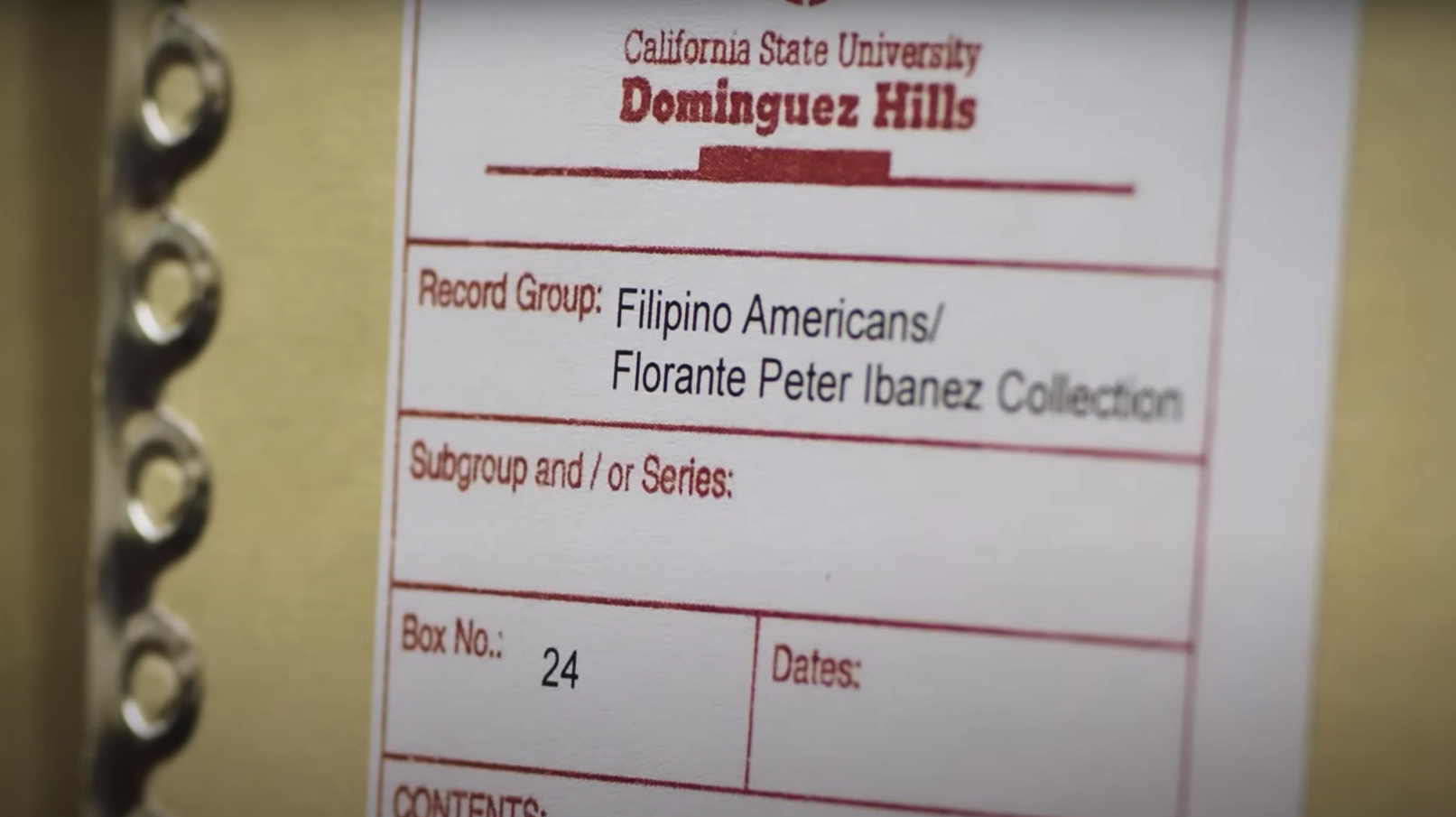

The exhibition Brackish Water Los Angeles (12 August-14 December) examines the crossover between built infrastructure and the natural world, using the California State University campus at Dominguez Hills as its inspiration.

Located on the Dominguez watershed for the Los Angeles River, the campus is at the centre of an urgent conversation about water. Wetlands are like lungs for the ecosystem, and when the Army Corps of Civil Engineers paved over and channelled the river with concrete between the late 1930s and the 60s, the exhibition’s co-curator Debra Scacco says they stripped “the earth of its natural capacity to breathe. And I think of this whole show as a number of breaths”.

Scacco worked with Aandrea Stang, the director of the California State University Art Gallery and the university’s students to create the exhibition, pulling in John Keyantash, head of earth sciences on campus, for his expertise on hydrology. Part artefact-collecting field trip, part science lecture, part art class, the exercise had students conducting research and combing archives. As well as research materials located by the students, the exhibition includes works by the painter Laddie John Dill, the interdisciplinary photographer Catherine Opie, and the experimental artists Newton and Helen Mayer Harrison, all based in Southern California.

Technically, brackish water is where freshwater meets the sea—but for Stang and Scacco and their students, it is an extended metaphor for in-betweenness, whether that is the slippages between art and archive, dry and wet land or student and teacher. “Access and agency have been our twin North Stars for this project,” Stang says. “We’re happy to be using the opportunity given to us by the Getty to empower students and to expand their access to art spaces.”

Stewarding the future

Clockshop, an arts non-profit based in Elysian Valley, will present a series of workshops and events along with an installation by the artist Rosten Woo. The What Water Wants series centres conversations about the cycles of the natural world and the relationships that humans forge with them. “The framework gives water itself some agency, and not just as a resource but as a system throughout the region,” says Sue Bell Yank, the executive director of Clockshop, whose premises sit alongside the Los Angeles River. “What [Woo] is really curious about is not the river itself but the watershed as a whole, like how do all the pieces of this system work together?”

Clockshop sits within the Bowtie—an 18-acre site that was once a railroad switch for the Union Pacific Railroad. Construction will soon start to restore the wetland habitat, which will help to drain stormwater and allow the land to breathe. Woo’s research and engagement with Clockshop’s neighbours, along with oral histories from the project Take Me To Your River, will culminate in a series of temporary signage installations.

“I’m hopeful some of these events and artistic installations can empower communities to think through these issues more and become strong stewards of their own place,” Bell Yank says. “That’s the connection we at Clockshop are trying to draw. How can we become our own advocates? How can communities become advocates for the places that they live in, in service of this kind of future where there is a more balanced relationship between the city and the natural ecology that we live in?”

Decontamination

Over at the Huntington, Storm Cloud: Picturing the Origins of Our Climate Crisis (14 September-6 January 2025) wrangles a dense and historic narrative about industrialisation and the environment in the years between 1780 and 1930. The title is inspired by a lecture given by John Ruskin, the 19th-century writer and art critic, who described contemporary changes in the colour of the sky because of industrial pollution, and the exhibition carries the story forward to Los Angeles and California in the first decades of the 20th century. From drawings to oil paintings, Storm Cloud addresses the West’s early relationship with environmentalism and climate science and flashes a mirror to our era of contemporary catastrophe.

Pollution is also a concern of Sinks: Places We Call Home (21 September-15 February 2025) at Self Help Graphics & Art. Marvella Muro, the institution’s director of artistic, curatorial and education programmes, says the show addresses two distinct cases of contamination in

Los Angeles County with different approaches in storytelling and research. Both centre community voices, bolstered by research-driven art-making and soil science. Two local toxic sites, the Exide battery plant in Vernon and Exxon Mobil’s former Athens Tank Farm site in Willowbrook, have been contaminating the water and soil of surrounding communities of colour.

The PB acronym for Prospering Backyards, the project and organisation of artist and chemist Maru Garcia, refers to the high levels of lead found in the water and soil of neighbourhoods near the Exide battery plant. In collaboration with scientist Aaron Celestian, Garcia has identified a zeolite, a white mineral that, when pulverised with contaminated soil, locks in surrounding lead like a sponge. Through community members in City Terrace, East Los Angeles, Boyle Heights and Huntington Park, they tested contaminated soil with zeolite and found that levels of toxic lead were decreasing.

With artist Beatriz Jaramillo, the team at Self Help Graphics & Art have established a monthly workshop at Willowbrook Community Garden. “We are led by them,” Muro says. “We use our garden as our canvas for these workshops and we invite other individuals who are experts in food sustainability practices as well as Indigenous practices.”

Muro’s goals are to involve members of the community and provide them with clear strategies for how they can help. “I want people to leave the exhibition with tangible resources—of how to take action, how to change and be proactive within their home. Don’t leave with a sense of hopelessness. [Visitors should] look upon their community members and each other to move forward with the collective work that we need to do.”

PST Art: Art & Science Collide opens in September 2024.