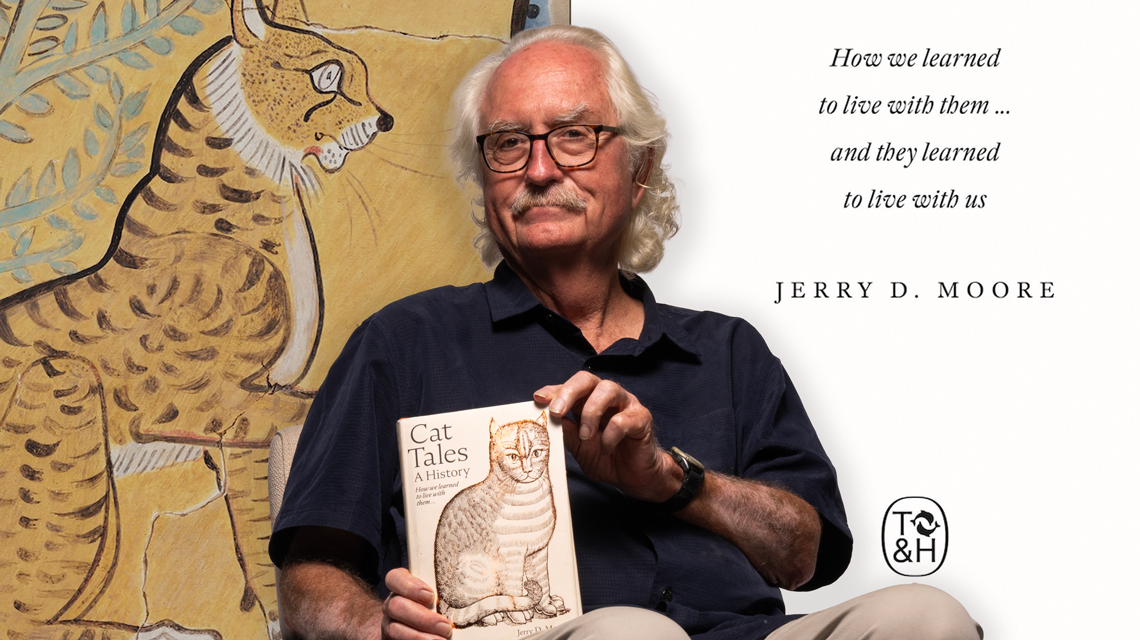

CSUDH Emeritus Professor of Anthropology Jerry Moore has a simple explanation for why he decided to delve into the history of human interaction with cats. “I’ve had cats,” he says, “and I was never really certain why!”

As an anthropological archeologist, Moore is keenly interested in the way in which his experience as a human being corresponds—or doesn’t—to the experiences of others. “All of my research is basically about the ways in which my history and human history are connected.”

Moore began looking into the history of cats and humans living together and was struck by how different the domestication process was from other animals. Typically, animals were brought into human society to perform specific tasks, such as using horses or donkeys as beasts of burden, or dogs to help herd animals or protect flocks.

That wasn’t true in the case of cats, though. “I wanted to explore through archeology what the attractions between humans and cats might have been, when they occurred, and what they could tell us about the felines in our own living rooms,” he says.

The results of Moore’s research are on display in his new book, Cat Tales: A History, in which he uses the latest archaeological evidence to trace the cat’s path from deadly enemy to unlikely roommate. This is no dry textbook, though—Moore’s cat tales are aimed at anyone who’s ever wondered how their feline friends went from stalking the wilderness to lying on their laptop during Zoom meetings.

Divided into chapters exploring specific aspects of feline/human interaction, the book explores topics such as how our ancient ancestors interacted with feline predators, why humans find cats to be “charismatic,” how cats ended up sailing the ancient world, and how cats adapted to urban environments.

Moore’s research (and that of others that he draws upon) points to the establishment of agriculture—and particularly the beginnings of storing food supplies—as the key turning point in the domestication of cats. “But what’s so interesting is that the process of growing and storing food doesn’t necessarily lead to the domestication of cats,” says Moore. “It didn’t happen everywhere.”

When Moore started the project, “I expected to see parallel developments in the Americas and the Near East,” he says. “Lots of folks talk about the Near East as the cradle of civilization, and as a New World archeologist, I’m pretty skeptical of those claims, because I know that they’re generally false.”

In this case, though, Moore found that domestic cats are actually all descended from one specific wild species that hails from northern Africa: felis silvestris lybica, or the African Wildcat.

The evidence also shows that it wasn’t simply that the domestication of wheat and grains attracted mice, which then attracted cats. The arrival of cats was triggered by the expansion of one particular species of mouse, originally from the Himalayas—mus musculus domesticus, or the house mouse.

“The house mouse started moving west and began to establish itself in different areas across Europe as agriculture spread,” says Moore. “That seems to have created enough of a rodent food base to attracts the wild cats, the fearless felis silvestris, to move onto the scene.

“What’s fascinating is that there are other places where food was stored, for example, in the Americas with corn. We actually have a few places where people have identified the remains of wild mice in the granaries, but there’s no evidence of a parallel process of feline domestication like in the Near East.

“As far as the relationship between cats and humans, that really does seem to be something that originates in northern Africa, with that specific type of cat, and spreads throughout the world.”

Illustrated throughout with photographs, artifacts, and artwork, the book delivers a lively survey of our relationships with cats from the Paleolithic period to the present day. Even an experienced scholar like Moore found lots of intriguing facts about humans and cats living in proximity during his research.

One of the things that Moore found most interesting was that there are two metropolitan areas in the world where large wild cats roam. “One is Mumbai,” says Moore. “The other is Los Angeles!”

“We’re still interacting with these wild animals in ways that are easy to forget,” he continues. “We’re here in our networks of freeways or at home with our internet and seem pretty isolated from the world that our Pleistocene ancestors occupied. Yet, despite all the obvious differences, there are still connections.”

“I think that’s really fascinating and may be one of the most fundamental things to take away from the book.”

Cat Tales: A History is available at bookstores or online.