In March, CSUDH hosted more than a dozen scholars from across the country for a three-day conference on Ethnic Studies Education. The event was made possible by a grant from the Education Research Conferences Program of the American Educational Research Association (AERA).

The conference, held from March 8-10, coincides with a contentious national debate over how educators should be allowed to address racial inequity in the classroom and what pedagogical tools they should be permitted to employ.

Much of the work of Ethnic Studies Education–as well as dealing with the pushback from political leaders, faculty colleagues, and students–is something that educators in the discipline often experience in isolation, says Tracy Buenavista, professor of Asian American Studies at CSU Northridge.

“This conference is really an opportunity for educators to come together and affirm the important work they’re doing, and also for us to think about ways to make our work more intentionally collaborative,” Buenavista says.

It also offered the chance to create a new model for academic conferences–one that doesn’t move at a breakneck pace right from the start, says Edward Curammeng, associate professor and graduate program director in CSUDH’s College of Education.

“We’ve been spending so much time sharing each other’s stories, listening and checking in, and moving at the pace of the group,” Curammeng says. “Spaces in higher education can be very violent. We’re asking how we can be more restorative.”

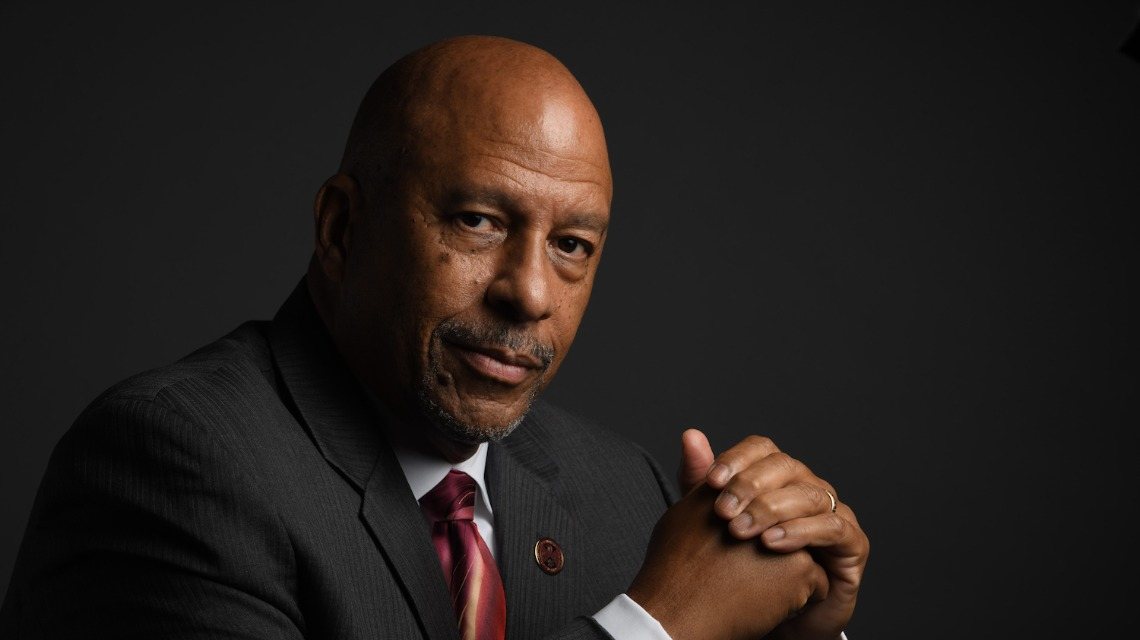

David Stovall is a professor in the departments of Black Studies and Criminology, Law and Justice at the University of Illinois at Chicago. With Curammeng and Buenavista, he served as a principal investigator for the Ethnic Studies Education conference.

“One of our colleagues recently said that if you’re engaged in Ethnic Studies, are you willing to ask the question, ‘Do students have a deeper sense of love for themselves as a result of the work that you’re doing?’” Stovall says.

“That’s antithetical to traditional research, but it’s a really important reminder for me in terms of how to keep our sights on the most important part of the work we do.”

The stakes for Ethnic Studies Education can be high, says Allyson Tintiangco-Cubales, a professor in the College of Ethnic Studies at San Francisco State University who mentored Curammeng and Buenavista as graduate students.

“I took my first Ethnic Studies class as a community college student in 1989. It was a class that changed my life. In many ways, it saved my life,” Tintiangco-Cubales says. “A big part of Ethnic Studies is bringing marginalized voices to the center. But the real goal is liberation. The real goal is to eradicate racism. That’s the part that makes some people uncomfortable.”

Daniel Solórzano is a professor in the Graduate School of Education at UCLA, where he also serves as director of the Center for Critical Race Studies in Education. His research and teaching have influenced generations of Ethnic Studies students, including many conference attendees, but his journey began humbly enough at an East LA public library.

“We didn’t even have a library at my elementary school. So the nuns told me to go to the Lincoln Heights library, a small community library where I grew up,” Solórzano told the conference. The librarian introduced him to Jet magazine.

“I wrote a book report on Black baseball players, and that opened me up to a whole area about which I had no clue. As I got older, Jet was a big part of my curriculum. It introduced me to Malcolm X and the Black Power movement,” Solózano said.

The conference was a first step toward preparing a book proposal to be submitted to AERA on Ethnic Studies Education, Curammeng says. “We’ll consider what that handbook might look like, but we’re also looking for sponsors to fund additional symposia and expand our network.”

In the meantime, the work inside the conference and among Ethnic Studies educators is helping the discipline evolve, says Buenavista.

“When people think about Ethnic Studies, they think about how we have to describe the oppression and damage that has been done to our communities,” she says.

“What I think all the scholars are doing here in terms of Ethnic Studies Education is reframing the starting point as the present goodness, the joy and thriving within communities of color, instead of just the racial equity gaps.”