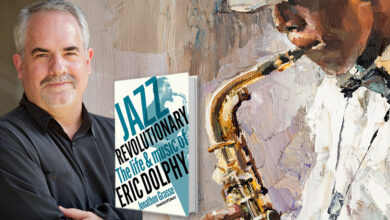

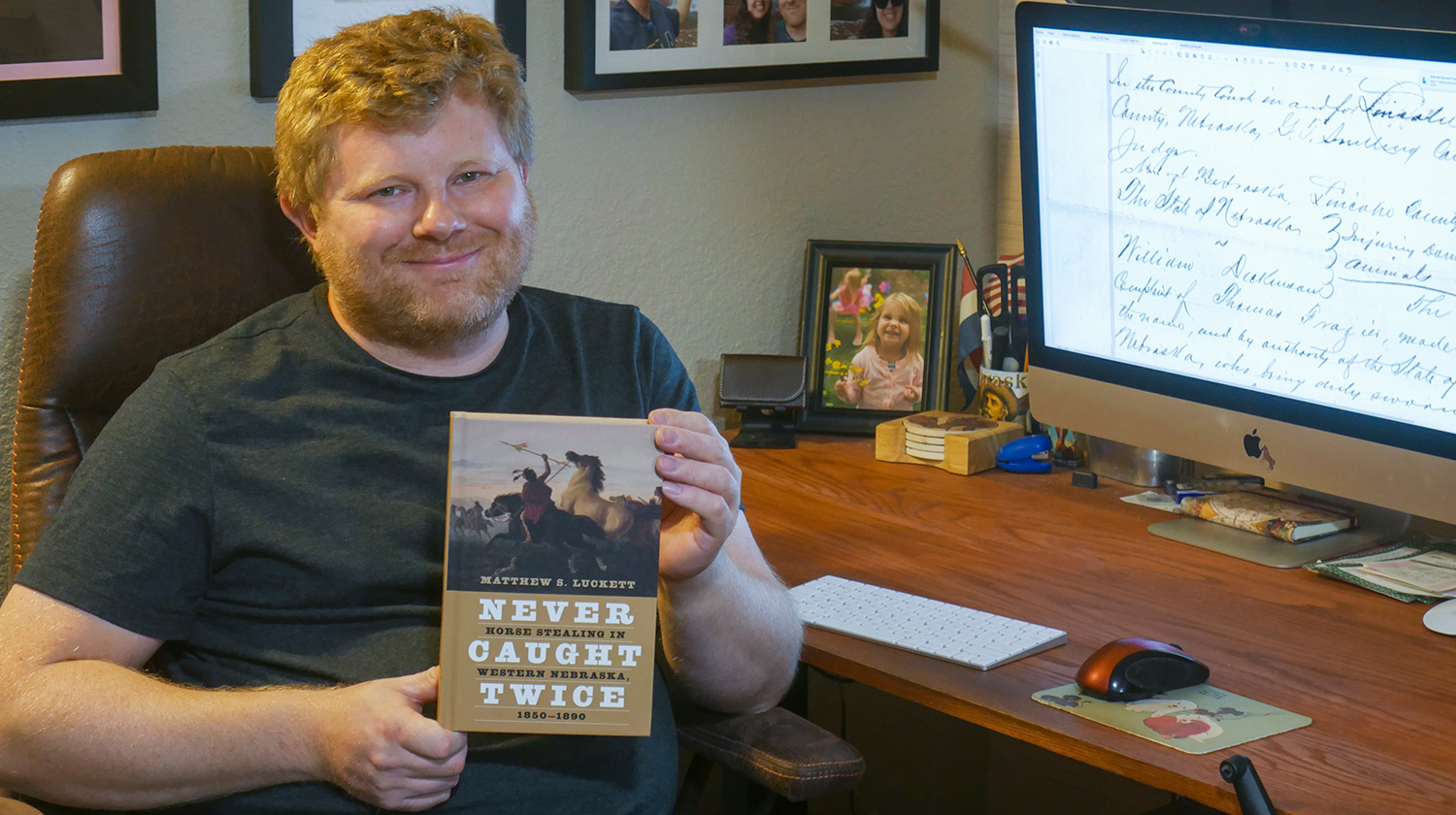

Riffling through dusty files in an old shed behind a courthouse in Chadron, Nebraska, External Master’s in Humanities academic coordinator Matthew Luckett scanned ledgers and criminal case files that had not been touched in decades. He was looking for horse thieves as part of his research for his book “Never Caught Twice: Horse Stealing in Western Nebraska, 1850-1890.”

The book, published by the University of Nebraska Press, documents the widely misunderstood crime in American mythology of horse stealing, revealing that it was perpetrated by four main Western Plains groups whose crimes inadvertently transformed plains culture and settlement. For some, violence was the solution for combating horse thievery, which potentially established the vigilantism that remains in American culture today.

Luckett believes that much of the content in his book has never been researched before. He found that four Plains groups–American Indians, the U.S. Army, ranchers and cowboys, and farmers–were responsible for much of the horse thievery on the Western Plains. From Lakota and Cheyenne horse raids to rustling gangs in the Sandhills of Nebraska, the crime was widespread and devastating across the region.

“Never Caught Twice” is available on Amazon. Click here for more information.

Along with visiting courthouses in the Midwest, Luckett conducted some of his research at the National Archives in Washington D.C.; the Nebraska State Historical Society in Lincoln, Nebraska; and the Autry Museum of the American West in Burbank. He found that horses were not only of critical importance in both Native American and white societies, but their theft undermined communities and jeopardized the peace in the region, causing people to act furiously in defense of their most expensive possession and beloved property.

“There was a time when horses were incredibly important. They were pets, friends, and part of the family, as well as valuable, utilitarian, and an indispensable means of production that was hard to replace,” says Luckett, who taught at CSUDH from 2013 to 2018.

The Great Plains in the mid- to late-1800s had a “cash poor economy.” Luckett explains: “Not a lot of people had enough money on hand to purchase a new horse. When a horse was stolen or died, they needed to replace it the next day, but that was typically beyond the means of most farmers and ranchers. On the other hand, horse thievery was one thing that people could potentially do something about.”

For a time, horse stealing and raids were a reciprocal response, according to Luckett. “If someone stole your horses then you would go steal some back. Ranchers would do the same thing. It was a culture of stealing. What changed this were the homesteaders.”

Luckett says that homesteaders were not like the cowboys, who worked ranches with dozens of men, hundreds of horses, and thousands of cattle. “Sometimes homesteaders would be lucky to have one horse, or would have to lease a horse, only owning 20 percent of it. So, when they arrived on the Great Plains they would demand that the police provide them with private property protection.”

However, law enforcement officers did not make a lot of money and did not have the resources to track horse thieves through hundreds of miles of open land, Luckett adds. “People would try to supplement law enforcement themselves. This is where the idea that horse thieves were always hanged came from, but that didn’t happen. Horse thieves were seldom caught. When they were caught and convicted, they would go to prison.”

Cowboys were notorious horse thieves on the Plains, according to Luckett. They only made about a dollar a day for four or five months out of the year.

“That’s not a lot of money. This was the Western Great Plains, and it wasn’t like you could go on unemployment,” he said. “They would quickly run out of cash and to survive they would steal horses, cattle, and other things. They would change the branding on animals and sell them in places like Omaha where no one knew the stolen brands. They got away with it because they were the ones doing the record keeping and guarding the horses and the cattle.”

Stealing horses had been a part of Plains Indian culture long before Anglo-American expansionists arrived, Luckett explains. However, he found that once the U.S. government relegated Native Americans to reservations, they were often more victim to horse raiding than thief.

“Then ranchers began going onto the reservations and stealing their horses. So not only was Indian land taken, but so was their livelihood,” he explains. “The army protected ranchers and settlers from Plains Indian horse thieves, but the opposite wasn’t true whenever white people would go up there [reservations] and bring them back down to Nebraska or Kansas.”

Luckett draws a parallel from modern life in the U.S. to horse stealing on the Great Plains. “Today, many Americans still guard their possessions with the threat of violence,” he says. “The reality is, the things we try to protect the most are insured, but we continue to view private property as something that justifies using vigilante justice to protect, and even lethal force. Where does that idea come from? I think those old horse thieves could provide an answer to that.”