Todd Matsubara (Class of ’11, B.S., business administration) is proof positive that one can go home again. After dropping out of California State University, Dominguez Hills in the early 1990s, he returned nearly two decades later to complete his degree. This past May, the 43-year-old graduated cum laude as a McNair Scholar and will begin the Transportation Science Graduate Program at University of California, Irvine this fall with the hopes of eventually earning a doctorate and entering a career in academia–possibly at his alma mater.

Matsubara had a personal example to draw from in his journey to complete a college education. As the son and grandson of Japanese and Japanese Americans incarcerated in camps during World War II, he learned from his family’s history the cost of dreams and ambition that are put on hold.

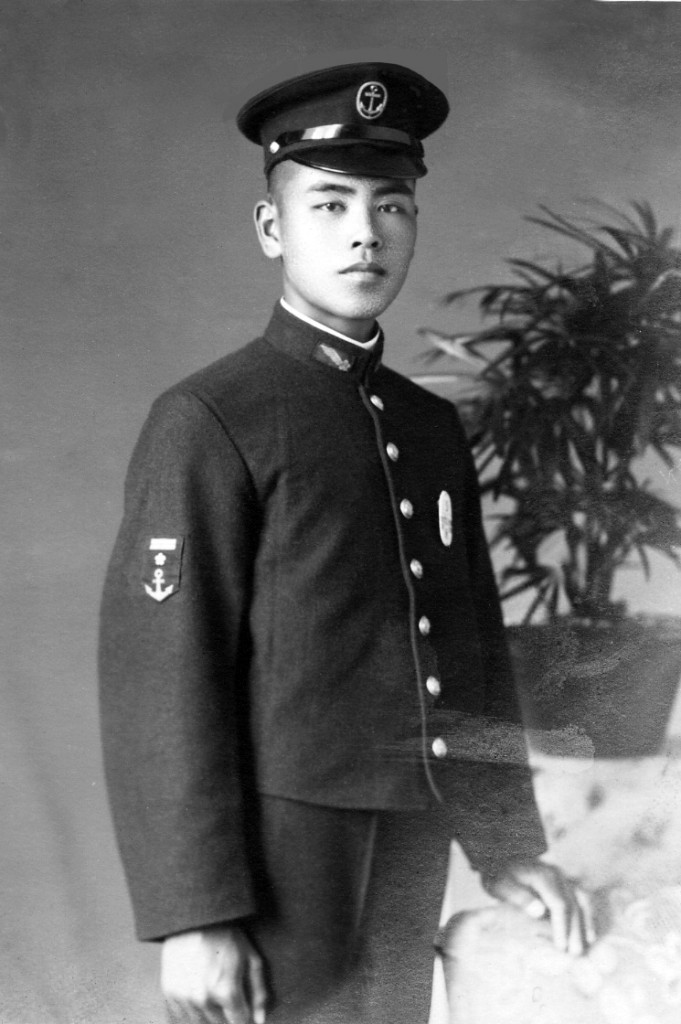

Matsubara’s paternal grandfather, Nobuyori Matsubara, was born in Tottori, Japan and emigrated to the United States in the 1920s with his father and brother. He was running his own restaurant when the U.S. government enacted Executive Order 9066, which mandated the imprisonment of Japanese Americans after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. He was sent to the camp at Tule Lake in northern California, with his youngest daughter, as well as his brother and family. To complicate matters, Nobuyori’s wife, Masuko, their oldest daughter Haruko, and son, Hiroshi, happened to be in Japan at the time. His wife and daughter were detained there for the duration of the war, while Hiroshi- who would become Matsubara’s father – was “drafted” into the Japanese Imperial Army and forced to train as a kamikaze pilot to fight against his native United States.

“Apparently being drafted was more like being kidnapped and forced to train and serve, with daily beatings and horrible treatment,” says Matsubara of his father’s wartime experience. “Luckily, he did not complete his training before the war ended. He stayed [in Japan] for 10 more years for some schooling, but ultimately moved back to Los Angeles.”

His mother’s family, who were living in Lima, Peru, at the time, was also incarcerated during the war in an agreement between the U.S. Department of State and certain South American countries to send Japanese living in those countries to the U.S. The Nakamatsu family were put in a camp at Crystal City, Texas, which is where they were held until the end of the war.

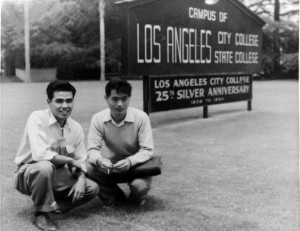

After the war, the Matsubara family returned to Los Angeles and began to rebuild their lives from scratch. The Nakamatsu side of the family remained in the United States, ending up in central California working in strawberry fields.

“After WWII, after losing everything and having to start from scratch, my grandparents and their kids worked the old fashioned way, doing whatever they could to get by,” Matsubara says. “For that next generation, when they finally went on their way as young adults, they continued doing the same.”

He says that as a result of his parents never completing their college education, he and his sister, Lynn, who earned her bachelor’s degree in graphic art at CSU Long Beach, were encouraged to do better. Although his parents were very patient with his extended attempts at college, he says that they were “pretty disappointed when I stopped.”

“I recall their constant pleading to just keep going and not to quit, no matter how slowly I went or how long it took,” he says. “My mother passed away suddenly from a stroke in 1997, barely two years after I quit attending Dominguez Hills, so I felt even guiltier that she didn’t have the satisfaction of seeing me finish college.

“Although they never said it, I know my parents felt unaccomplished as far as their education went –and it showed when they would tell my sister and me that we had to finish college if we wanted to go anywhere in life. It’s normal for all parents to want to see their children accomplish more than they did, but I think for them it had even more meaning because of the hardships that they and my grandparents faced.”

Matsubara’s earlier college career ended due to a lack of commitment and what proved to be a profitable distraction–his interest in car audio.

“Back then, the higher end setups involved a great deal of engineering, know-how, and ingenuity to create accurate and realistic sound in an automobile,” says Matsubara, who became a technical and contributing editor for industry magazines through his self-taught expertise.

“The manufacturers actually had some serious sponsored competitions to find out who was the best of the best,” Matsubara recalls. “There was no Internet [to show how to do things], and you knew what you were doing from being smart–or you didn’t.”

He eventually landed a job as a design engineer at Clarion Corporation of America, a top-tier audio supplier to automotive manufacturers, which led him to drop out of college. The experience taught Matsubara about production, efficiency, suppliers, and the way the auto industry operates on a large scale. After three years, the company downsized and eliminated his entire department. He decided that it was time to open his own business in manufacturing performance auto parts and customizing vehicles.

“I already had an excellent network in place of customers and industry contacts, so it was a natural transition to give my own business a try,” says Matsubara, who founded TM Engineering in Carson in 1999. “I did make sure of one thing however, which was to locate my business as close as possible to the Dominguez Hills campus so that I could return to school when I felt the time was right.”

Although the business was a success, Matsubara always felt that he was missing out by discontinuing his college education. He says that he grew to realize the value of a college degree as the job market changed.

“When I first started college, I took business as my major as it seemed like that was what one should do if they were going to get a job in the world of ‘business,’” says Matsubara. “Of course, I had no idea what that could or would actually lead to, [but] I figured I was doing the right thing to lead myself to a career in an office somewhere.

In 2002, with TM Engineering running smoothly, Matsubara decided to go back to school. Unfortunately, his spotty transcripts showed a higher ratio of dropped versus completed classes and his application was rejected.

Finally, in 2008, while watching a friend graduate from Pepperdine with her MBA, Matsubara realized that he would need a college degree–and ultimately, an MBA–to ensure a career in case the economic downturn necessitated closing TM Engineering. He credits Dr. Kaye Bragg, then associate dean of the College of Business Administration and Public Policy (currently acting dean), and associate professor of information systems and operations management. Dr. Hamid Pourmohammadi with giving him a new lease on his academic life.

“After her thorough assessment of my transcript and with a well-laid plan to remedy my horrific previous performance–along with plenty of groveling and begging and my promise to continue on to an MBA– [Dr. Bragg] agreed to readmit me,” Matsubara says. “I built a good rapport with my professors and ended up changing my major from management to global logistics and supply chain management. I also took the full gamut of classes for a marketing concentration. Dr. Pourmohammadi mentored me and pointed me down a more academic path, away from my MBA intentions and toward a Ph.D. and teaching.”

Matsubara would like to return to CSU Dominguez Hills in the future–as a faculty member in the operations management department of CBAPP. He hopes that students will benefit from his experience, both as a professional and a former student.

“The Global Logistics and Supply Chain Management undergraduate concentration is already a great program with two different tracks to choose from, thanks to all of the hard work by my mentor Dr. Pourmohammadi,” he says. “I would love to be able to add to that and make it even more interesting and useful for students’ career paths. I definitely feel that my real-world work experience will help me to explain things in an easier-to- grasp manner as opposed to someone who has not had the same experience.

“Having attended CSU Dominguez Hills as not only a transfer student, but also as both a younger and older student gives me a unique perspective of what it takes to make the material interesting to the students, no matter what their background, age, or demographic.”

He also hopes that his experience as a returning student will serve as an example for others to never give up.

“After accomplishing what I have, and after bringing my GPA up to 3.53, I’m not embarrassed to tell everyone that my GPA was at 0.75 at that time,” Matsubara says of his determination to return to college despite his poor academic standing. “In fact, I hope that this can be an inspiration to others that you can always salvage things if you are willing to put forth the effort.”