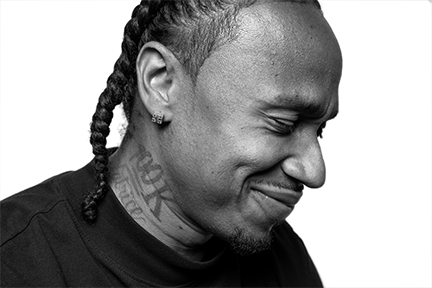

Christopher Carson once found himself on a dangerous trajectory. He was born and raised on 107th Street and South Vermont Avenue, an area long acquainted with gang culture and the violence that accompanies it. “It’s what you’re used to when you live with it,” says Carson. “It’s what you know.”

In 2016, a court convicted Carson of attempted murder and sentenced him to 12 years in prison. But for the steadfast love of family and friends, and the timely intervention of unexpected mentors, Carson might have succumbed to the hopelessness of the prison industrial complex and come to believe that he would only ever be defined by his mistakes.

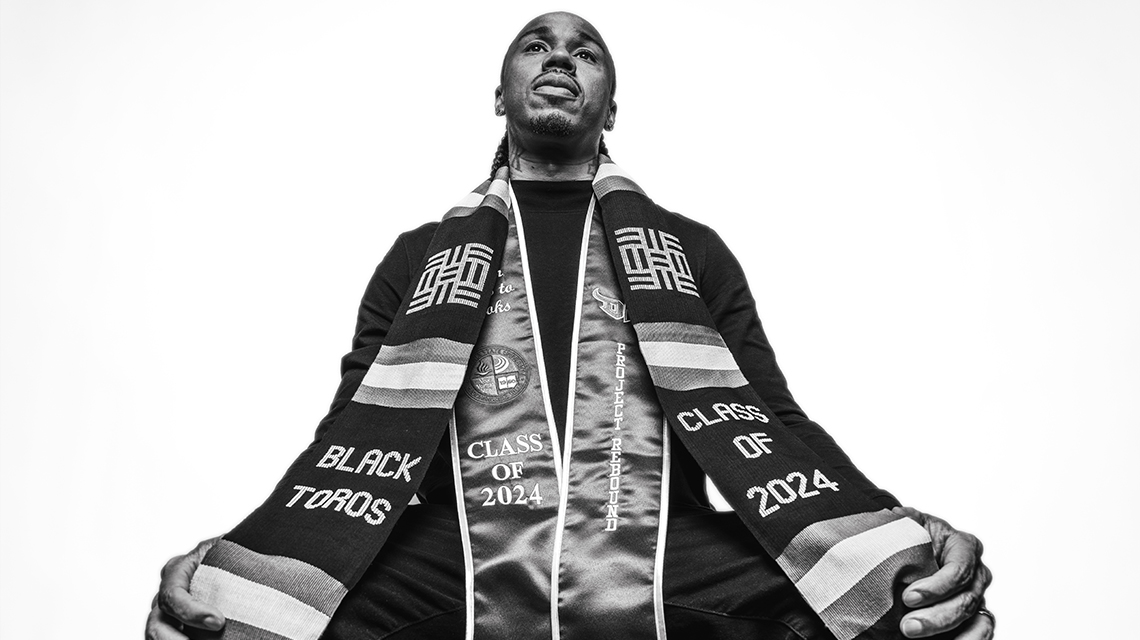

Instead, he joined some 4,400 other students on May 17, receiving his bachelor’s degree in sociology from California State University, Dominguez Hills. The last to walk during the second ceremony of the day, Carson ascended the stage in the tennis stadium at Dignity Health Sports Park with confidence and resolve.

Thomas A. Parham, president of CSUDH, came to the podium and paused the proceedings unexpectedly, while William Franklin, vice president for Student Affairs, joined Carson at the front of the stage. “People come from circumstances, and I remind us all, ladies and gentlemen, that we are not our circumstances,” said Parham.

“Chris…stumbled, but he got back up, dusted himself off, planted himself in the nurturing soil of CSUDH, and now graduates with his degree.” Though Carson’s confidence never wavered, the intense vulnerability of the moment brought tears to his eyes as the stadium audience erupted in applause.

“I’ve had some good moments in my life,” says Carson. “That was one of the best because of the new person I am. It felt like Dr. Parham wasn’t talking about me but talking directly to me. It was special to me that he took the time to say, ‘Look at what this man has just done.’ How can’t you be proud of that?”

Carson grew up on a stretch of South Vermont extending north from Imperial Highway dubbed “Death Alley” in 2014 by the Los Angeles Times for the frequency of gang-related homicides there. Some of his friendships made gang affiliation a likely outcome, but his love for football kept that life at bay for a time.

“I went to a couple different high schools—Washington and Westchester—but I played my senior year at Gardena and won a state championship.” College recruiters began to take notice. He enrolled in East Los Angeles College, where his talents as a receiver earned him a scholarship to Weber State University in Ogden, Utah.

It was during a visit home to California, Carson says, that he fell back in with the wrong people. “I ended up getting shot. That’s when my life turned a whole other way. I started getting back into the culture.”

Carson spent a month recovering from his injuries, but an even greater tragedy lay ahead. In 2015, his brother was shot and killed. “His death turned me into a whole other person. It flipped my whole mindset toward retaliation.”

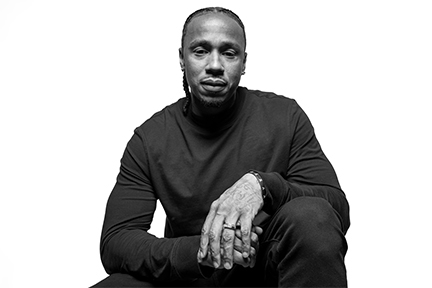

After his 2016 conviction for attempted murder, Carson entered Solano State Prison—a medium-security facility with a population of more than 3,300. It was here that he began the long journey back. He found mentors among the long-term inmates that helped him navigate prison politics and stay out of trouble.

Leanilla Hunter met Carson before his incarceration, and the two were married in 2020. She played an integral role in shaping the man he’s become. “We met at a time when I was really depressed after my brother died,” says Carson. “She was the one person where I could totally be myself. She’s my rock. She helped me change.”

While in prison, Carson joined a re-entry program intended to support inmates near the end of their sentences. It was during his supervised residency in the community that Carson encountered Project Rebound at CSUDH.

Project Rebound provides support services that create a pathway for formerly incarcerated individuals to find transformation through education, says Sean James, director of the Educational Opportunity Program (EOP) and Project Rebound at CSUDH. It began at San Francisco State University and now operates on 19 campuses within the CSU system. It launched at CSUDH last year and currently supports 10 students.

“There are some unique needs and support systems that need to be developed for this population to be successful, and also unique skill sets that need to be learned, unlearned and relearned for them to be ready to transition back into society and engage with them being professionals,” James says.

Carson credits James and the staff he assembled at EOP for making him feel welcome and helping him learn how to trust people in a way that he never had before. “It’s hard to change. Sean made it easier. He believed in me like nobody else ever had. Every person in this office was always open to me, always welcoming. Who wouldn’t want to change when you have this kind of support and this kind of love?”

Javier Cuevas recently joined Project Rebound as a program coordinator. He’s worked closely with Carson and understands the challenges he faced, as an alum of the same program at CSU Long Beach.

“Project Rebound offers that tailored support for this population of students because they’re constantly doubting their potential and constantly doubting whether or not they belong in school,” Cuevas said. “We reassure them and instill that sense of belonging because as different as we are, we’re all chasing the same goal, which is education.”

This customized support has shown incredible results across the CSU system. Retention rates among Project Rebound students over the last several years have been higher than CSU students.

Furthermore, access to higher education and support throughout the process has made it far more likely that this population of students will transform their lives as well as the communities to which they return. From 2016 to 2020, the recidivism rate for students in the program was zero.

Creating institutional space for Project Rebound students to form lasting connections that affirm their dignity and humanity is essential, says Jennifer Macy, professor of criminal justice administration at CSUDH. “We held a storytelling event recently that went well beyond our imaginations in terms of how successful it was,” says Macy.

“It demonstrated how brave these students are, and how compelling and powerful their stories are and how much we can learn from them. In that moment, it made me understand how much we as a university need our Project Rebound students as much as they need the support the program provides.”

For James, it’s the emphasis on creating a culture of care that makes the most difference in the lives of students transitioning from incarceration to education, and then to professional lives after graduation. “We conceived this program as an extension of this goal of creating a culture of care at CSUDH. Students have challenged us to stay true to that goal. You can’t fake it with this population.”

Standing with family, friends, and fellow graduates after commencement, Carson is focused on appreciating the moment and celebrating the people who helped position him for a better future.

Carson hasn’t just received support through Project Rebound. He’s also been able to give back. Speaking recently at an event for high school students, Carson noticed a group of kids whose behavior and attitude reminded him of his younger self, and he pulled them aside. “Nobody asked me to do that. I just saw it as an opportunity.” At the end of the day, he says, they’ll make their own choices. “All I could do was give them my input and tell them what will happen before it happens. Because I know how that life ends.”

“I’m so happy, and so proud of my son,” says Latrice Marsh. “He came here and did it, pushed all the way through. There’s no stopping him.”

His sister Alecia Bridgefort says Carson’s confidence often got mistaken for arrogance. “There’s no self-doubt, no insecurity. He carries himself with confidence. No matter what he went through, he’s always had confidence in who he was.”

For Hunter, Carson’s wife, commencement is just the beginning. “He’s worked so hard for this, and I’m so proud of him. I want him to keep going. He could change a lot of lives—young kids going in the direction he went in—and show them how he turned his life around.”

If there’s a moral to his story, Carson says, it’s that you don’t give in. There’s always a way forward if you’re willing to work for it and you put yourself in a position to receive the help you need. “You get caught up and go down the wrong path,” Carson says. “You do something you shouldn’t have done, but you don’t give up on anybody. You can never give up on anybody.”