After the ancient city of Ek’ Balam–with its remarkably well preserved Maya sculptures–was unearthed on the Yucatán Peninsula in the late 1980s, the Mexican government gave control of the site to local indigenous villagers to create an authentic Maya tourist destination, and in the process, improve their overall prosperity.

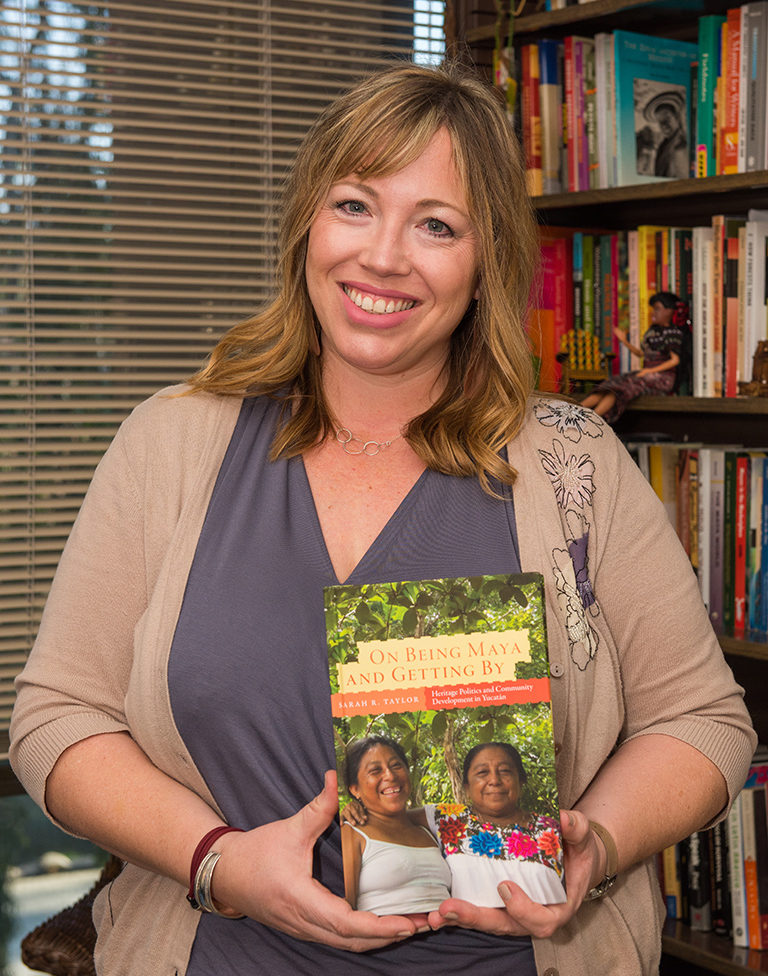

Sarah R. Taylor, assistant professor of anthropology at California State University, Dominguez Hills (CSUDH), has been researching the Ek’ Balam’s community-based economic development project since 2004 and the effects tourism and growth have had on the rural Maya village. She has chronicled her findings in her new book, On Being Maya and Getting By: Heritage Politics and Community Development in Yucatán (University Press of Colorado, 2018).

An ethnographic study, Taylor’s book examines how one community is navigating the expectations of a modern world while maintaining their cultural roots.

“The villagers have become very good at balancing the line between their culture and what a modern village should be,” Taylor says. “They’re still Maya and indigenous, but they are also really excited about having cable television. An indigenous person might be on a mobile phone while working as a village guide or waitress during the day, then sit down to a meal with food grown in the forest the same way it has grown for 4,000 years.”

Ek’ Balam–the name includes both the archeological site and the modern Maya village–lies in the Northern lowlands on the Yucatán Peninsula and was once part of the seat of the Maya kingdom. Among its 45 structures is a pyramid with public access, the Oval Palace that contained burial relics, and the elaborate tomb of king Ukit Kan Le’k Tok’, one of the best preserved façades of ceramic sculpture in the Maya world.

Taylor, who has taught at CSUDH since 2016, began her research at Ek’ Balam while a student CSU Chico, after receiving an undergraduate award for research and creativity grant from the university.

“When I would go there, I lived with a family, who form part of the structure of the book. They would talk to me about their day–the work in the village. A lot of my time was spent just walking around talking to people and conducting interviews,” says Taylor. “Having access to different people and perspectives made a huge difference in my research and book.”

The Maya village, and its more than 350 indigenous people, is approximately 300 meters away from the still-active archaeological site they manage. By the mid-2000s, three hotels had been built within their small village and Ek’ Balam had become a major tourist attraction on the peninsula.

Taylor has involved numerous students in her ethnographic research. Most recently she has opened the CSUDH Guatemala Ethnographic Field School, which gives students opportunity to learn ethnographic methods while immersed in the culture of the region.

Next to touring the ruins, visitors to Ek’ Balam are most curious about the villagers’ culture, says Taylor. “One Maya woman decided to start bringing them into her home to teach them how to make tortillas and show them around. She didn’t get any advice about how to run a tour; she figured it out on her own. She also thought that they might like to see her grandparents’ old stone corn grinder instead of her metal one. They loved that, too.”

Tourism has helped this Maya woman profit from her culture, but it has also helped revitalize old ways, Taylor said The woman lived in a home constructed with traditional Maya building methods–raw materials and without screws or nails–but it was aging and becoming dilapidated. That method of construction had been lost to the village’s newer generation, and the woman sought to bring it back.

“She wanted to rebuild it exactly the same way, but the young men of the village didn’t know the traditional methods. They had to be taught how to use vines and plant materials from the forest before they could build it,” Taylor says. “I share this because it’s a perfect example of how tourism doesn’t have to come in a change everything, or completely transform an indigenous way of life.

In fact, old traditions can re-emerge and guests can get that authentic experience that they really want.

Unfortunately, not all the villagers have been able to get in on the prosperity, says Taylor. At Ek’ Balam, the Mexican government put 26 Maya families in charge of running operations, which was its practice at the time.

“It was a good idea, and in many cases the idea worked. The landowners have benefited in exciting ways–extra income and kids are now going to school nearby, but other families have been marginalized in the community for generations and don’t have any access to the jobs. It’s a microcosm of everywhere else in the world, but still a great example of how important culture is to all people; both their own traditions and others’,” she says.

Taylor is still engaged with Ek’ Balam. Her new project studies the social mores that stingless bees represent–an alternative form of traditional ecological knowledge–that influence Ek’ Balam residents’ perception of collective work, community relations, and the importance of inter-generational remembering.”

“More recently I’ve become involved in a new native bee reintroduction project in Ek’Balam. These native, stingless bees were kept by the ancient Maya, but have been disappearing over the past 100 years,” she shared.

Taylor explains why she is particularly excited about this new project. “It shows us that cultural traditions may not always be ‘traditional’ in the way we may think. Much like the case of tourism development in Ek’Balam, the new market for Melipona honey is reinvigorating a cultural practice that was in decline. That’s an interesting place for an anthropologist to be.”