I recently cared for a man in his early 60s who had been without insurance and out of his medication for over a month. We were able to help him refill all of his prescriptions, get current on all of his lab work, and find more permanent shelter for him and his wife. In today’s busy health-care world with 15- and 30-minute appointment slots, it was nice to see that, while his visit took well over an hour, he got the care he needed. Sometimes we just have to slow down and realize what matters most for the patient sitting in front of us. – Kendall Galvez

Kendall Galvez works in the rural town of Cloverdale with a population of about 9,000 in Northern California. She graduated in 2011 from CSU Dominguez Hills with a Bachelor of Science in Nursing, and has returned to earn her family nurse practitioner master’s degree.

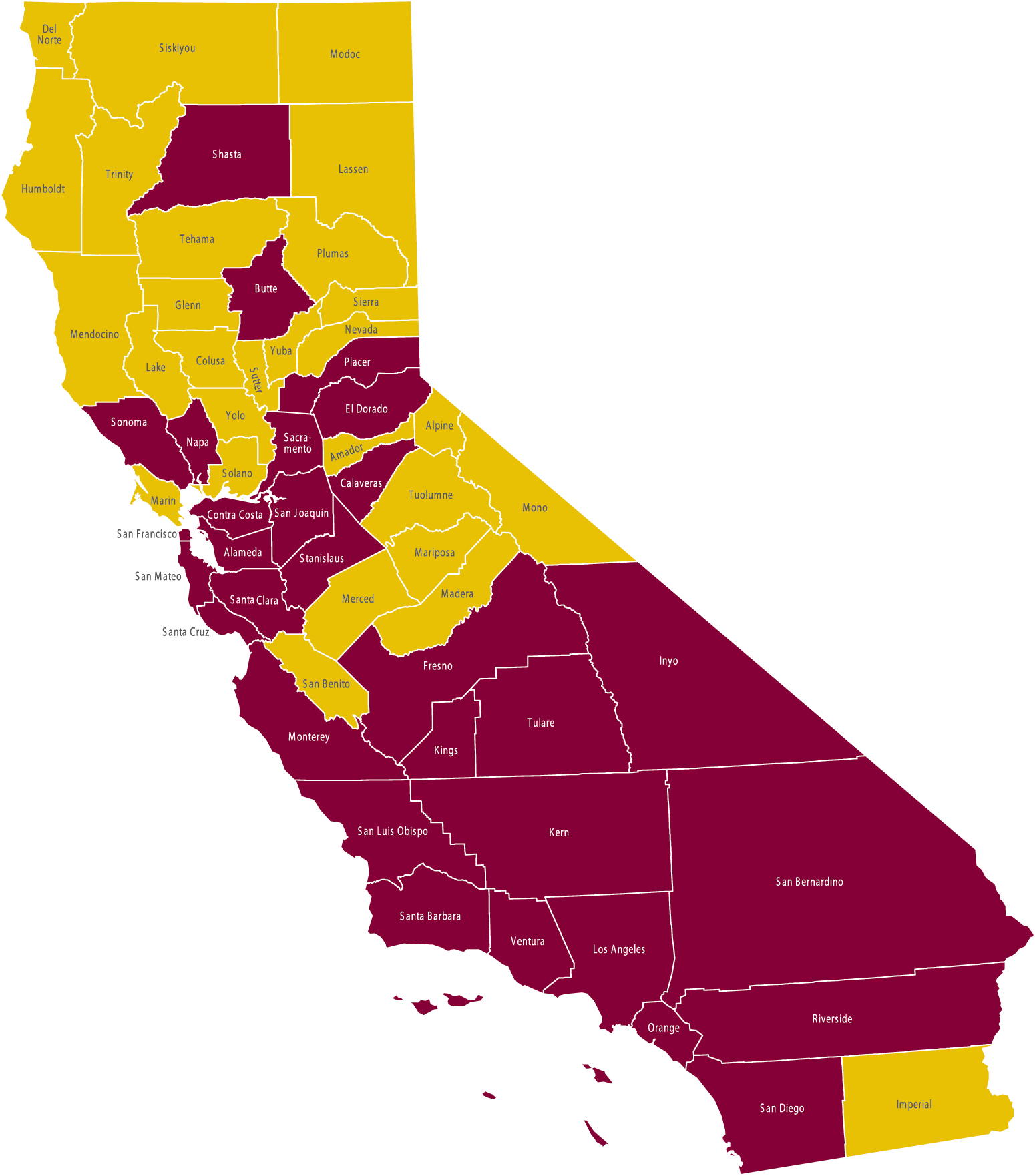

Galvez is among the thousands of nurses up and down California who have enhanced their nursing careers through CSUDH programs over the last three decades. The Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BSN) and the Master of Science in Nursing (MSN) degrees at Dominguez Hills are both offered online, allowing the university to provide an education for nursing students in far-flung areas of the state, many of which are rural, poor, and underserved.

“We see all ages from birth to geriatrics and all walks of life from the homeless to those who are better off and have health insurance,” says Galvez, who works in the Alexander Valley Health Care Center, the only health-care clinic within a 15-mile radius. “We have a large population of migrant workers in our area, and many of them frequent the clinic to take advantage of some of our free programs.”

School of Nursing

School of Nursing

CSU Dominguez Hills first offered the online option to nursing students in 1999, effectively removing geographical barriers for students–especially those who do not live near a university with a nursing program. This allows for working professionals to tailor the time, location, and pace of study to their personal lives and work schedules.

“Many of our students attend an online program because they work full-time, have families to raise, and can eliminate time commuting to and from campus,” says Kathleen Tornow Chai, interim director of nursing at CSUDH. “Instead of lectures, students gain knowledge through readings and group work. Courses are capped at 25 students or less, the same ratios that onsite courses have.”

The program helps address the shortage of nurses in underserved areas, serving to mitigate a potential exodus from the profession, as some trend-watchers predict, when younger baby boomers and older members of Generation X begin to retire in the next decade. The BSN and MSN programs have more than 1,000 students currently enrolled. Galvez is one of several CSUDH students able to offset the expenses of her education with the support of two Song-Brown Health Care Workforce Training Act grants, totaling $136,000 through 2017, awarded to CSUDH from the state specifically to support students who work in underserved locations.

“Our students are doing clinical work from Butte County to Compton,” adds Chai. “They work on Indian reservations and in inner cities. As far as serving the underserved, I think that it also relates to social justice. Nurses have the ability to serve through their work, involvement in the community, and involvement in other organizations. They impact the health of the community.”

I work at Harbor-UCLA in a trauma and surgical intensive care unit, and we get really busy. I take care of two critically ill patients at a time, and most of the patients are victims of vehicle accidents or were hit by a car, have had a stroke, have fallen or are gunshot victims. We accept everyone regardless of their ability to pay, including homeless people and those with no identification. – Khaing Zarchi Nwe

Khaing Zarchi Nwe is currently a registered nurse pursuing a BSN degree at Dominguez Hills. She describes her day-to-day work and the reasons she pursued this profession. “Working in an underserved community is deeply personal to me. I came from Myanmar, which was ruled by a dictator, and people could not express their opinions. No health insurance exists, and when you were sick, you had to pay first to get treated. I’ve seen people die from diseases that could easily be treated,” says Nwe. “My mother was a physician, and when I was young, I helped out in her private clinic, and the joy of seeing people get better, and their appreciation, inspired me to become a nurse.”

This will be the third summer my husband and I will join a team providing medical services to indigent families in the border town of Vicente Guerrero in Mexico. I grew up in a Hispanic family of eight with no health insurance. My parents emigrated from Mexico, and I only spoke Spanish when I started school. I know first-hand the struggles with language and culture many hardworking families experience to get the medical services they need. – Lupe Rincon

Lupe Rincon, who lives in Napa, California, just finished a portion of her clinical work at Ole Health and is working on her CSUDH master’s in nursing with the help of a Song-Brown award. At the clinic, she recently cared for a Spanish-speaking woman with a bulging disc on her spine who had come from another clinic where she was refused care because there had no interpreter. “This experience was very similar to those I had growing up,” says Rincon, “but this inspires me to improve the system.”

A few years back, my son was born prematurely, and I was told he would die. But I kept my faith in God, and with the help and constant support of all the nurses, I was able to take my healthy son home in two months. Those nurses made a difference in my life, and I changed my major from accounting to nursing, because I wanted to give the same kind of hope, comfort, and care those nurses gave me. – Anne-marie Bialeu

Anne-marie Bialeu works for Maxim Healthcare Services as a home health nurse in Garden Grove. She’s currently pursuing a BSN at Dominguez Hills and plans to earn a master’s at the university. She was among several undergraduate nursing students who recently presented health information to residents at the Midnight Mission on Skid Row in Downtown Los Angeles. “The visit gave me a much better understanding about their daily battles against poverty, drugs, alcoholism, and the importance of a structured environment,” says Bialeu. “First-hand encounters with diverse patients make me a better person and a better nurse.”

My family left communist Soviet Union without anything and migrated to the U.S. in 1992 in search of a better life. We depended on public support, and I was 10 when I became ill and was transported to a county facility. We felt vulnerable and thought we were being taken to the ‘poor’ hospital and worried about the treatment. But, it was the best medical service we’d ever received. Today, when I see patients, I see myself and my family more than 20 years ago, and I have a special place in my heart for the underserved population. – Vahagn Nacharyan

Vahagn Nacharyan is a registered nurse and will finish his master’s in nursing at CSUDH this year with the help of a Song-Brown award. Nacharyan works at Olive View-UCLA Medical Center. “This is a county hospital, and there is nothing ‘poor’ about the services we provide; our services are pure quality and pure care,” he says. However, Nacharyan has witnessed the influx of patients in the emergency room waiting for as long as 10 hours with ailments that could be treated at an out-patient clinic. “There are important new initiatives and funding for greater collaboration between county and community clinics,” he says. “I want to be part of this movement.”

Written by Laurie McLaughlin. This story first appeared in the Summer 2016 issue of the university magazine, Dominguez Today.