When Professor of Biology Terry McGlynn writes about teaching on his blog Small Pond Science, he often receives comments from science instructors who are dedicated to their students but admit they lack formal pedagogical training.

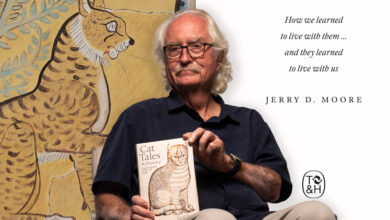

With his new book The Chicago Guide to College Science Teaching, McGlynn offers a practical guide for anyone teaching STEM disciplines at the college level, from newly appointed faculty and graduate students teaching lab sections, to well-seasoned professors seeking new and creative ideas.

McGlynn, a recognized expert in the biology of ants and how insects respond to challenging environments, orients his research program around providing students the opportunity to conduct fieldwork, often in tropical rainforests.

“As a fellow scientist who recognizes the value of discipline-based educational research, I want to help other scientists become more dynamic teachers,” says McGlynn, who is the director of undergraduate research at California State University, Dominguez Hills (CSUDH). “I believe that is done by engaging with students respectfully and creating the right opportunities for student to learn. Unfortunately, these are critical skills that are often not taught at Ph.D. granting institutions.”

To find The Chicago Guide to College Science Teaching by CSUDH Biology Professor Terry McGlynn visit https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/C/bo27808232.html. Check out McGlynn’s writings and musings at https://smallpondscience.com/.

For years, McGlynn has been addressing the need for practical and accessible advice for science teachers on his blog, which is also a space where he shares his research. His aim with the book was to consolidate the teaching advice from the blog using a straightforward approach that avoids academic jargon and enables instructors to build strong connections and a love for science for their students. In his book, readers learn about topics ranging from creating a syllabus and developing grading rubrics, to mastering learning management systems and ensuring safety during lab and fieldwork.

“Learning how to structure a course that is a practical educational experience isn’t necessarily straight forward,” McGlynn says. “The craft of teaching isn’t something that you can magically be good at. It’s important to engage with theory and what is known to work, and there is a whole body of knowledge about science education out there. As we teach the science, it only makes sense that we should implement evidence-based practices in our own classrooms.”

A Need for Change

However, McGlynn says a lot of faculty who want to follow evidenced-based teaching practices have not done the necessary research, such as reviewing the primary literature written by experts in teaching methods.

“From the very beginning, graduate school in the sciences involves teaching, but there is this notion in academia that when trained to teach grad students simply absorb the good practices that they experience,” McGlynn explains. “Unfortunately, all too often those experiences are created by educators who also were never really trained to teach.”

After they complete their doctorate programs and are hired by universities to teach undergraduate students, over time many will begin to view research and the training of researchers as their primary job, and teaching secondary.

“The incentive structure in higher education that graduate students are exposed to overly focuses on research productivity and raising research funding.” McGlynn says. “That needs to change. Since so many scientists go into teaching, I think learning to become effective at teaching should become foundational and embedded in all Ph.D. and graduate school curricula, and in professional training for all science faculty.”

McGlynn’s book could help graduate program creators in that regard, but he says “Science first needs to value its own people and the lived experience of others more, because in higher education, people are often the product of the culture from which they came.”

“Some use the Golden Rule when it comes to teaching – treat others as you would like to be treated,” he adds. “That’s a real problem. The Platinum Rule is better. Treat people like they would like to be treated, otherwise new teachers will just keep trying to teach the way they think works best for them, and not necessarily their students.”