Edwin Henderson might not live anywhere near CSUDH, but his experience after taking teacher credential courses here shows how the Toro community’s commitment to social justice transcends distance and history.

Henderson taught elementary school in the Compton Unified School District in the 1980s, attending CSUDH to take the required courses to renew his teaching credential. He later moved to Falls Church, Virginia, teaching in public schools there until his retirement in 2012.

It was there in Northern Virginia that Henderson started his work commemorating the region’s early civil rights history. He founded the Tinner Hill Heritage Foundation in 1997 to research and preserve the critical contributions that its Black residents have made to the fight for local and national civil rights.

Henderson’s own family history is inextricably linked to that fight. In 1915, town leaders proposed an ordinance that would have removed most of the Black residents of Falls Church by segregating the town’s districts along racial lines. Henderson’s grandparents, E.B. and Mary Henderson, joined other community leaders to form the Colored Citizens Protective League, which later became an NAACP chapter, to fight the plan.

Two years later, the Supreme Court addressed the issue in Buchanan v. Warley. “The court ruled that redistricting along racial lines was unconstitutional, giving Falls Church an important victory,” says Henderson.

In partnership with George Mason University, Henderson’s foundation created a website that explores local African American history in a video titled 100 Years of Black Falls Church. The roots of this community go back to early Colonial America in 1699, says Henderson, whose ancestors were among the first formerly enslaved people to purchase property in the area during the Civil War.

The earliest Black inhabitants of Falls Church established themselves as farmers, business owners, craftsmen, and landowners. The community thrived despite the challenges of enslavement, segregation, and the menace of Jim Crow in the decades that followed.

“The Black community in Falls Church wanted to be a part of America,” Henderson states in an interview included in the video project. “Coming from nothing, working hard and attaining a piece of land to call their own was very important to them.”

A Neglected Black Icon

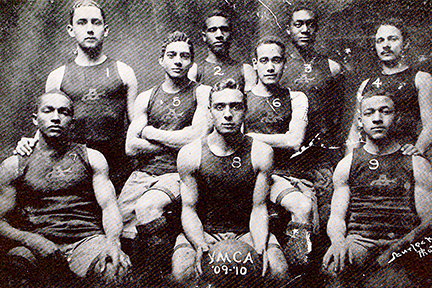

Henderson’s grandfather was more than just a civil rights activist. E.B. Henderson also left an indelible mark on organized athletics. He introduced the fledgling sport of basketball to the Black community in Washington, D.C., in 1904, having learned the game while attending Harvard University’s Dudley Sargent School of Physical Training.

His contributions to the sport were largely forgotten for more than a century until Henderson nominated his grandfather for induction into the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame in Springfield, Massachusetts. “My wife and I put together a 138-page document with letters from John Hope Franklin, Henry Louis Gates, Jr., leaders of the NAACP, and all the organizations and athletic associations at the Historically Black Colleges and Universities.”

Their efforts received little traction until they supplemented the nomination packet with a video clip of tennis legend Arthur Ashe being interviewed about Henderson’s grandfather by Bryant Gumbel on the Today Show. After eight years of painstaking research and documentation, E.B. Henderson was inducted in 2013 and dubbed the ‘Grandfather of Black Basketball.”

Earlier this year, Henderson published a biography titled The Grandfather of Black Basketball: The Life and Times of Dr. E.B. Henderson, in which he chronicles his journey to restore his grandfather’s historical legacy. “What my grandfather did was lay the infrastructure for Blacks to participate in organized sports,” Henderson told NBA.com in a 2024 interview about the book.

Stories are powerful, and it matters who tells them, says Henderson. “I’ve always considered myself a storyteller, and it’s important to me that African Americans tell their own stories.” That’s as true in Falls Church, he adds, as it is in other communities of color that have been historically overlooked and underserved.

“When I attended CSUDH in the 1980s, it was an institution dedicated primarily to working professionals,” says Henderson, adding that it had much more to offer the local communities in South and South-Central Los Angeles. “The current vision for the university is remarkably dynamic as it continues to build a more community-focused campus that creates a platform for empowering and amplifying the voices of the diverse population that it serves.”