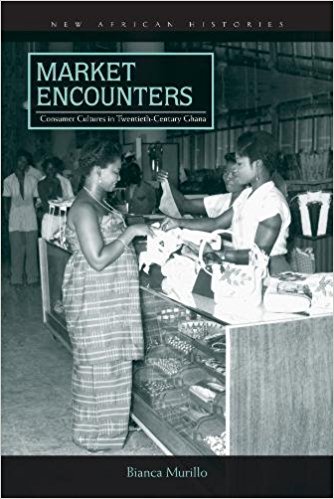

Associate Professor of History Bianca Murillo’s first book, “Market Encounters: Consumer Cultures in Twentieth Century Ghana” (Ohio University Press, 2017), provides an expansive perspective of global capitalism that examines how race, gender, and power are created through commercial networks, and offers a radical rethinking of how economies and markets function.

Associate Professor of History Bianca Murillo’s first book, “Market Encounters: Consumer Cultures in Twentieth Century Ghana” (Ohio University Press, 2017), provides an expansive perspective of global capitalism that examines how race, gender, and power are created through commercial networks, and offers a radical rethinking of how economies and markets function.

Funded by the Fulbright Hays Program and the Woodrow Wilson Foundation, Murillo conducted extensive research in the U.K., Europe, and West Africa to trace the evolution of consumerism in the colonial Gold Coast and independent Ghana as far back as the late 19th Century. But while much of the research for her book was spent scouring corporate archives on two continents, its stories are best illustrated through oral histories Murillo conducted with everyday retailers and consumers, as well as former employees of the United Africa Company (UAC), the British trading giant that the book primarily focuses on. The company operated in West Africa from 1929 until it was absorbed by its parent company Unilever in 1987.

Born and raised in the San Francisco Bay area, Murillo received her Ph.D. in African history from UC Santa Barbara (UCSB) in 2009, and earned a doctoral emphasis focused on gender and labor from UCSB’s Department of Feminist Studies. She received the 2015-2016 Graves Award in the Humanities (administered by the American Council for Learned Societies) for her “outstanding teaching ” from Willamette University, where she served as assistant professor of history before coming to CSUDH in fall 2016.

Murillo has lived and worked in Ghana off and on for close to 14 years, and has also worked in other African countries including, Senegal, Burkina Faso, Egypt, and Morocco. She shares those experiences, her scholarship, and love of history with CSUDH Campus News Center.

Q: What were some of your goals for this book?

A: I wanted to understand the intersections between colonialism and capitalism from an Africa-centered perspective. To do this, I had to revisit the histories of old colonial trading firms, like the UAC and others that tend to be a bit dull and impersonal; full of statistics, facts and names. My underlying goal for the book was to bring the market and the UAC to life through the people who experienced it. This approach was challenging and took me to every corner of Ghana just looking for people who used to work with or for the company. Social networks in Ghana are extensive, so if you have an old photo and a name, it’s possible to find someone. Plus, everyone in Ghana knows the UAC. The company basically had a monopoly on the West African import/export business, so its activities reached every corner of the country. Another goal for the book was to make it teachable. It’s 204 pages long, which is considered short for a history book, so students can read half in one week and finish it up the next. Each chapter can stand on its own as a short case study so a professor could also assign just one chapter in a business or social history, or a global studies class. There’s something for everyone.

Q: How would you say your research on this area of African history differs from other historians?

A: The book makes an important methodological intervention by fusing business and economic history with social and cultural history. To do so, I had to put two seemingly distinct types of sources in conversation–corporate archives and oral histories. I wanted to show the range of experiences that animated individual encounters with the market from all different vantage points. African history is rich and comprised of a multitude of stories, so I also wanted to push back against old, tired narratives of Africans within world economic history books as simply industrial laborers and producers of raw materials.

Bianca Murillo’s writing has been published in the journals Africa, Enterprise & Society, and Gender & History. Her current project is a comparative history of West African security guards, security work, and migration in cities like Accra, Los Angeles, and London.

Q: Can you briefly summarize your overall research findings from the book?

A: Global markets were contested spaces, but not always in the ways we might assume. Economic realities in 20th-Century Ghana were shaped by battles against colonialism and neocolonial domination, as well as on-going controversies over the meanings of wealth and proper accumulation, the role of the state and political authority, and the formation of gendered and racial ideologies. The importance of a group that I call “commercial intermediaries”– African shopkeepers, clerks, assistants, credit customers–were also instrumental in shaping the development of Ghana’s economy.

Q: How did Africa and Ghana first get on your radar?

A: Courses as an undergraduate definitely sparked my interest in Africa. Specifically, reading African writers. Novels by authors like Buchi Emecheta and Ama Aidoo were among my favorites, and I still teach them today. This interest expanded even more when I studied Islamic history abroad in North Africa. Ghana, however, will always be the place I return to. As a student, I was drawn to theories about decolonization, liberation, and global solidarity. In 1957, Ghana was the first sub-Saharan African country to gain political independence. It therefore holds a unique space within social, political, and intellectual narratives from this period. In the 1950s and 60s, it was a major international destination for anti-colonial activists, scholars, writers, and feminist thinkers. The country was, and still is, a place of radical possibilities.

Q: How do you translate your research and travel experiences into teaching for your students?

A: My classes are really interactive and participatory. I found that engaging with students in this way is crucial to moving them from an old remember, recite, and regurgitate model of studying history to a new place where they are active critical thinkers. In the process, I really urge students to understand history, not as a set of events to be memorized, but as a generative tool–one that allows us to ask new questions about our sources, our interests, and the world. This approach is also key to teaching students how to interrogate and challenge older, more familiar ways of knowing–the hallmark of any type of critical studies.

As a historian of Africa, specifically, I am invested in using the classroom to challenge students’ assumptions about the continent as some place distant and different. You will often hear me saying that “students of African history are also historians of the world.” I assign materials that focus on the African past as one of dynamic interconnectivity, while centering continental and diasporan African experiences and knowledge. Lastly, the study of Africa demands a rigorous engagement with issues of power, privilege, and inequity. All of my courses therefore require students to immerse themselves in scholarly material, but also actively make connections to contemporary political and social issues, as well as their own research and advocacy projects.

Q: What do you love the most about history and teaching it?

A: Its transformative potential. Throughout my years teaching, I’ve seen the study of history spark major changes in students, and this goes beyond academics and intellectual development. Most inspiring for me is to see students apply historical thinking in creative and unexpected ways. I have former students who are professional artists, writers, and dancers, and others who work on Capitol Hill, travel abroad as nurses, and run community food co-ops.