Despite the economic downturn, holiday spending still happens, with shoppers looking for the perfect gift at a good price. As is often the case, the would-be Santas are also buying presents for themselves, many of which will end up in the backs of closets or otherwise never used.

This fall, in Anne Choi’s class on “American Consumerism,” students were asked to bring items to class that had caused them to feel buyer’s remorse. The session, which was recorded by American Public Media’s “Marketplace,” aired on NPR on Dec. 13.

Choi says that people often think they can buy happiness “because the media tells us that we can.”

“It has become easier to buy things than to do things that require time…like having dinner with friends or going on a walk,” said Choi. “But it doesn’t work because it is just a temporary fix. The act of purchasing gives us a temporary high but nothing has really changed. You haven’t made any deeper connections with someone or yourself …you just have more stuff.”

Sandy Navarro said that an artificial value is often attached to merchandise, either through the pressure on consumers to buy due to limited supply or with brand-name recognition.

“The Coach Store at the Ontario Mills outlet mall the weekend of Dec. 19 had a wait time of one hour to pay for any item,” she recalls. “The line took 45 minutes to enter the store. All this to by sunglasses – in the winter – they were 30% off.”

Navarro says that people often try to compensate for their insecurities through their purchasing.

“If a woman is short, they wear high heels,” she said. “If a parent is too busy working, then they overwhelm their children with material things that are meant to make up for missed time. If you live in a small house in a bad part of the city, no problem – overcompensate with a big flashy car that you can barely afford.

“More things are bought to compensate for lacking in a particular area,” said Navarro. “This contributes greatly to the disposable society that overconsumption has created.”

A pile of unused, unwanted items on a table at the front of Choi’s classroom revealed much about the students’ intentions as purchasers: expensive exercise equipment, clothing selected a size too small, and cookware whose design turned out to be either inefficient or unsafe. Undaunted, some sought to remedy bad purchases by making new ones.

“I thought I was a Food Network chef,” said Lynette Bell, showing off two large cast iron skillets with ridges meant to leave grillmarks on cooked meat. “I found out it was kind of dangerous the grease just runs off. So I said, ‘I’ll buy this one because it’s deeper.’ It’s supposed to [give you] the grill marks and the grilled taste – not true. The best thing is to buy a gas grill. [Food] tastes good and it’s not so dangerous.”

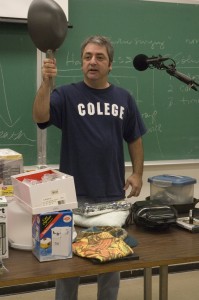

While most of the students presenting their examples of buyer’s remorse could not find a way to salvage their purchases, Eddie Moretti was able to find humor – and some justification – in his ill-conceived choices, as long as they were under a certain price point.

“It was five bucks,” he said, indicating his tee shirt with the wry misspelling of “Colege.”

“I kept it because I can change the oil in it. It was worth five bucks to wear it here. I’m not unsatisfied anymore.”

Choi said that while presents are a part of the holiday experience for children, most people give gifts out of obligation rather than genuine thoughtfulness.

“I think what most people want rather than another bathrobe or toaster is time spent with someone that they care about,” she says. “In many ways it’s not about the gift at all. The gift is supposed to represent caring, love, togetherness…and you can do all that without buying a thing.”

Choi is currently writing “Spent: Downward Mobility and the Middle Class,” which she hopes to publish in fall of 2011.

For the “Marketplace” segment on Choi’s class, click here.

For more information on interdisciplinary studies at CSU Dominguez Hills, click here.