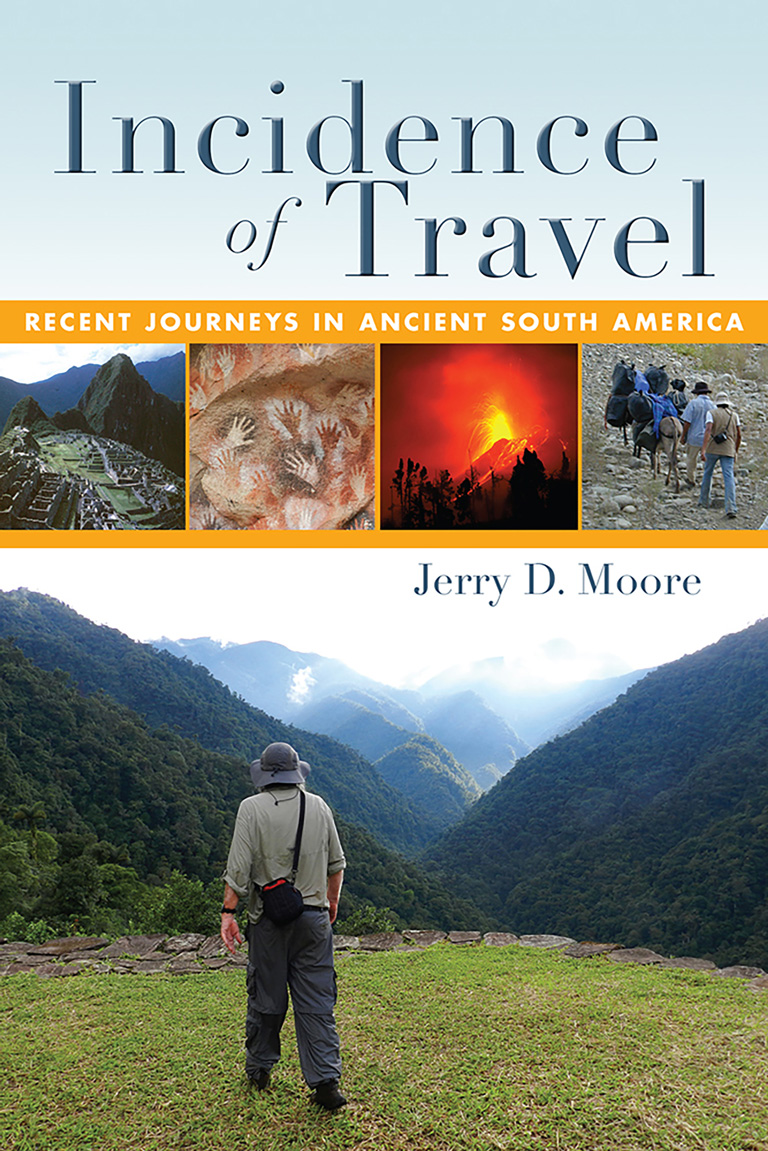

Jerry Moore, professor and chair of the Department of Anthropology at California State University, Dominguez Hills (CSUDH), has authored the book “Incidence of Travel: Recent Journeys in Ancient South America.” (University Press of Colorado, March 2017). In telling his stories, the award-winning author relives personal experiences and archaeological studies throughout South America to provide an understanding of the ways “traditional peoples” carved dynamic cultural landscapes in the region. Moore’s rich narration vividly acquaints readers with a variety of archaeological sites and remains as he reflects on what these places might have been like in the past.

Jerry Moore, professor and chair of the Department of Anthropology at California State University, Dominguez Hills (CSUDH), has authored the book “Incidence of Travel: Recent Journeys in Ancient South America.” (University Press of Colorado, March 2017). In telling his stories, the award-winning author relives personal experiences and archaeological studies throughout South America to provide an understanding of the ways “traditional peoples” carved dynamic cultural landscapes in the region. Moore’s rich narration vividly acquaints readers with a variety of archaeological sites and remains as he reflects on what these places might have been like in the past.

Moore’s other books include “Visions of Culture: An Introduction to Anthropological Theories and Theorists” (2012); “A Prehistory of Home,” the 2014 SAA Book Award winner; “Architecture and Power in the Prehispanic Andes: The Archaeology of Public Buildings” (1996); and “Cultural Landscapes in the Prehispanic Andes: Archaeologies of Place” (2005). He has also written 35 peer-reviewed articles and book chapters, and 73 professional papers.

What does “Incidence of Travel” mean in the context of your book?

Incidence is a term in physics referring to the movement of a body that intersects with a surface. For example, if you were to shoot a BB at a balloon, the incidence would be the angle of intersection between the path of the BB and the surface it encounters. So I think of these travels like that. I’m moving along these lines, some of which I planned and are well laid out, and others that were accidental incidents. It also plays on the titles of 19th Century travel narratives that were early versions of archaeological writings, such as John Lloyd Stephens’ “Incidents of Travel in Egypt, Arabia Petraea, and the Holy Land,” or Ephraim George Squier’s “Peru: Incidents of Travel and Exploration in the Land of the Incas.” Those books were bestsellers and widely reviewed in their time. I also used that title because I’d like to help reintroduce the role of travel narrative in archaeological writing, to share with readers what archaeology is and what archaeologists actually do. My ambition–and this sounds presumptuous–but my ambition is to do for archaeology what Oliver Sacks did for neuropsychology, or Jared Diamond has done for geography, which is to engage a general reader.

Jerry Moore will be honored for 25 years of service during the 2017 Faculty Awards Reception, March 23 from 5:30 to 8 p.m. in the Loker Student Union ballroom. Moore joined the Department of Anthropology in fall 1991. Since then, the department has grown from four faculty members serving approximately 325 students and 20 students majoring in anthropology, to five faculty members who teaching approximately 650 students and 60 to 70 students majoring in anthropology.

Does your book have a purpose beyond just being a good read?

What I tried to do in the book was take some of the big issues that we explore and, without diluting them, make those issues and explorations more accessible and real. Our earliest literature, and our earliest tales, are of journeys. So I have taken the journeys that I have made in South America to provide a firsthand, authentic look at the archaeology, the culture, the history, and the landscape that I encountered during those journeys, while trying to show the unique, beautiful, and sometimes unusual aspects of the human experience.

How did writing the book affect you emotionally and connect you to the places and cultures that you have experienced in South America?

I do not have the words to describe how exciting my work can be. If you’re excavating an archaeological site, there are times that you experience seemingly endless moments of boredom, knowing full-well that the boredom can be interrupted by explosive periods of excitement that are beyond anything that you would ever anticipate or expect. You never know when that can happen, which makes it all the more wonderful. That’s the thing. Whether it’s on a dig, or on a journey to or just through a new place, instantaneous excitement can occur at any time.

Would you describe one of your most interesting excursions featured in your book?

One of them has to be in Southern Patagonia in the province of Santa Cruz, Argentina, when we visited the Cueva de las Manos (Spanish for Cave of Hands). What they did was take a ground-up pigment mixed with some kind of mastic–we are not sure what it is, it could be blood or something else. They then had put in their mouth and blew it through a tube–probably made of the leg bone of Ñandú (South American ostrich)–on to their hands and the wall behind. The subject of the painting had to remain motionless for the 5 or 10 minutes required to make this stenciled painting of a human hand, and we know this because the edges of the images are crisp and not blurred. The real interesting thing is that the hand paintings date between 8,900 and 9,300 years ago. So, in this amazing wind-swept environment, where the wind is dominating force of nature, where humans were few and the landscape seems defined by impermanence, you see evidence for this amazing art, this fascinating human gesture stating “I was here.”

How have your students been involved in field work featured in “Incidence of Travel?”

A lot of them have been. There’s a chapter called “Making Mounds.” The chapter features a National Science Foundation-funded research project of excavations we did with students in northern Peru in 2007. We were excavating a prehistoric mound at a site where–we later learned–people had lived at various times from 3500 BC to AD 1500. But when we began excavations, we thought we were looking a “just” a mound, a simple construction built be either people mounding dirt or the by-product of people discarding garbage. In the chapter, I talk about how the students learned that things can be infinitely more complex than anticipated–how pieces of landscape look obvious and the reasons for their shape seem really clear-cut, but almost always hold this some kind of hidden buried secrets that occur in really surprising ways.

What experience featured in your book really blew your mind?

There is something like that in every chapter. In one chapter, I joined a pilgrimage processional to a secret lake in the Southern Ecuador. I wasn’t intruding; this was a solstice walk organized by a local museum and other cultural groups. Just the process of people walking together was amazing. We moved through the city of Cuenca Ecuador, into to the outskirts of town, through the countryside and toward this lake. Prayers were being offered, incense was burning, and music was playing. By the end of the tour you felt in some way that there’s been a transformation in you. It’s the sort of thing that attracts people to such events as Burning Man each year. It’s a very dynamic and profound intersection between movement, culture, and landscape. That’s really what the entire book is about.