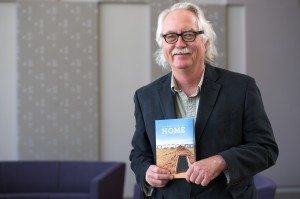

The concept of home has deep meaning for most people. It may go even deeper for Jerry Moore, professor of anthropology at California State University, Dominguez Hills. During his career as an anthropological archaeologist, he’s been – as he calls it – “digging into people’s home for 30 years,” searching for clues that help to unravel a fundamental question, what does it mean to be human? And, he has written about it in “The Prehistory of Home” (University of California Press, Berkeley, 2012).

“The human experience is such a vast topic, but breaking it down makes it digestible. Focusing on home was a good choice [for the book], because most anyone can relate to having a home or being brought up in one,” Moore said.

Homes reflect the people who live in them, and the homes, themselves, reshape the experiences of their inhabitants, according to Moore, whether from man’s first hut to an $85 million 57,000 square-foot Holmby Hills mega mansion.

“How we get there… that is a fascinating topic and what intrigued me to write this book,” Moore said.

In “The Prehistory of Home,” Moore goes as far back as Neanderthals to examine the creation of home. From their beginnings, he explained, homes had “…distinguishing cooking areas and tool-making spaces, differentiating the space of the living from the space of the dead. They exhibited this human propensity to create order at home.”

Equally versed in current times, Moore gives insights into the modern construction of homes. He said in post-1920s home life, the rise of companionate marriages over marriages of convenience led to a desire for more privacy, which resulted in a greater physical distance between the parent and children’s rooms.

“People no longer married primarily to have families, but they married for full, rich unions where husbands and wives were companions and sexual partners. Five-hundred years earlier the children slept in the family bed with parents,” said Moore.

With an archaeological passion that spans the ages, Moore has a knack for comparative analysis and has structured his book to juxtapose homes that are ancient and distant with homes that are modern and near.

“The very process of trying to make the past relevant to a modern reader requires from a writer to think about how the past intersects with the writer. At various parts of the book I write about my archeological experiences,” Moore said.

In one of his travels to sites worldwide, Moore visited farm house ruins in a potato famine village along the west coast of Ireland. As the scarcity of food drove out the Irish residents, their homes became ruins for later generations to ponder. In the book, Moore counter balances those observations with ones made during a brief modern archeological survey in Lancaster, Calif., which he called “the zip code with the highest rate of home foreclosures in Southern California.” The dwellings of both regions left behind chilling relics of their outward migration. Describing the evidence of the modern ruins in Lancaster, Moore said, “It’s really easy to see foreclosed homes. In fact, you can spot them a block away, because the lawns are dead.”

While discoveries through investigations such as these may seem mundane, it is the seemingly routine inspections that advance anthropological knowledge through archeology.

“Most people know what [archaeology] is, and most people are wrong,” said Moore with a hearty chuckle. “Everybody knows about Indiana Jones and Laura Croft tomb raider. But, what most folks don’t realize, on one hand what we do as archaeologists is not nearly as violent as the things they do. [On the other hand], most people don’t realize how small pieces of the past can lead to just stunning insights into the human experience.”

These insights are, however, sometimes inclusive, misleading, or insufficient to make comprehensive or accurate conclusions about what may have really occurred. For many, these ambiguities are construed as shortcomings in the practice of archaeology.

“For some people it is one of the most frustrating things about archaeology, but for most archaeologists it’s what we find most fascinating. We find these incredibly concrete traces of past lives; that corn cob, that skull, those beads. They’re there and behind them are all these enormously difficult to answer questions,” said Moore. “But in large part, that’s where all the fun is, trying to figure out these things.”

In addition to sometimes ambiguous findings, archaeologists are faced with the challenge of how to tell the world about what they do learn. While a good number of archaeologists could improve on communicating with the average reader, Moore said it isn’t entirely their fault. Needing to document findings, archaeologists often bury them in academic reports where the average reader is unlikely to go. Moore intends to reach those readers through his book and hopes to do the same with future projects. He said he would like to be “multi-lingual” – writing for academia and for a general commercial audience, adding that his conversational writing style comes from his teaching philosophy of keeping people interested.

“If you can’t engage people, you can’t teach them. I can’t teach students if they are asleep,” said Moore who has taught and engaged scores of students during his 20-year teaching career at CSU Dominguez Hills.

As for his book, the underlying lesson plan is as broad as the audience he hopes to attract.

“I want the reader to realize that they are a part of a broad shared legacy of what it means to be human.” Moore said. “And, homes have been a part of the human experience even longer than we have been Homo sapiens.”

“The Prehistory of Home” can be purchased now through University of California Press online or pre-ordered at Amazon.com. The book is scheduled to be released on April 18.

Moore, who earned a doctorate and a master’s degree in anthropology from the University of California, Santa Barbara; and a bachelor’s in anthropology from California State College, Stanislaus, specializes in prehistoric cultural landscapes and built environments, archaeology of Andean South America, and archaeology of Western North America. He has edited and authored several articles and books, including “Visions of Culture: An Introduction to Anthropological Theories and Theorists” (Altamira/Rowman and Littlefield Press; 1st edition, 1997; 2nd edition 2004; expanded 3rd edition, 2008; 4th edition, forthcoming 2012), “Cultural Landscapes in the Prehispanic Andes: Archaeologies of Place” (University Press of Florida, 2005), “Architecture and Power in the Prehispanic Andes: The Archaeology of Public Buildings” (Cambridge University Press, 1996).