To help dismantle systemic racism, white people need to first acknowledge that it exists–and how they personally benefit from it.

That was the central argument delivered by Robin DiAngelo to an audience of CSUDH students, faculty, staff, and community members at the University Theatre on February 1. DiAngelo, a bestselling author and academic specializing in whiteness and racism, was invited by the CSUDH Mervyn M. Dymally African American Political and Economic Institute for its Distinguished Speaker Series.

Dymally Executive Director Anthony Asadullah Samad kicked off the event by acknowledging that having a white featured speaker on the first day of Black History Month might seem counterintuitive.

“This is our way to invite our brothers and sisters of European descent into the conversation,” Samad said. “Who better to lead the discussion than an anti-racist scholar who has written about the vulnerability of white people?”

Vice President and Chief Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Officer Bobbie Porter also provided opening remarks. She called for the remembrance of Tyre Nichols, an unarmed Black man murdered by police officers last month, as well as the “urgent need to do the necessary work of racial justice.”

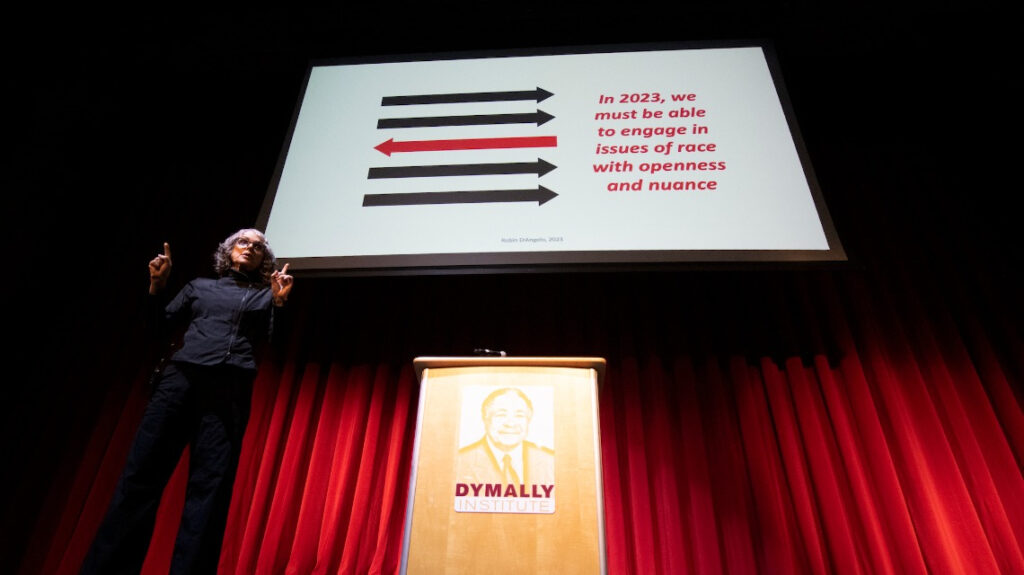

DiAngelo then took to the stage to deliver her lecture, which outlined a framework of systemic racism and the strategies white people use to exempt themselves from accountability. She offered herself as an “insider to whiteness” with the stated goal of helping people of color navigate conversations, situations, and institutions led by white people, and of helping white people to critically examine their own beliefs and biases.

She began by speaking about her personal history, revealing how she was brought up to view racism as something that “bad” white people did to people of color, and therefore was irrelevant to her life and responsibilities.

“Racism is a relationship,” DiAngelo said, “and I was not raised to see myself in racial terms.”

She went on to explain that systemic racism affects everyone–and that by not considering their own race and its accompanying privileges, white people excuse themselves from being part of an unjust system.

To demonstrate one aspect of systemic racism, DiAngelo presented data from the “halls of power,” which revealed the disproportionately high percentages of white people in government, media, academia, and leadership roles. All of the categories were at least 80 percent white, and more than half surpassed 90 percent.

“We see ourselves as unique individuals,” she said. “We need to suspend our focus on how different we are and be willing to grapple with collective experience. No one in this room was or could be exempt from the forces of this system.”

After carefully analyzing and debunking many of the common ways white people tell themselves they are not racist–including by having Black friends and family or “not seeing color”–DiAngelo offered concrete ways to become actively anti-racist. Strategies included continual self-education, ensuring inclusion of people of color in group dynamics, intervening in racist situations, being open to criticism, and staying accountable.

“This work requires courage and commitment to a lifelong process,” DiAngelo said. “Niceness is not anti-racism. Niceness is not courageous.”

Following her lecture, DiAngelo took questions from audience members on topics ranging from the intersectionality of class and racism, to racism perpetuated by people of color, to the reactions of white people to her book.

“If white people can hear it better when it comes from me, then I’m going to use this voice to help them hear it,” she said. “Then, hopefully, they start to listen to people of color.”