Alexis McCurn remembers the exchange she had one day with her neighbor, Ruth: She was sitting on the front steps of her former East Oakland apartment when the 19-year-old mother walked by pushing a stroller. McCurn asked, “Where you going, Ruth?”

“You know where I’m going, taking him to the babysitter, then to King’s (the local fast-food restaurant where she worked),” said Ruth. “I’ve gotta stay on my grind because the bills don’t stop.”

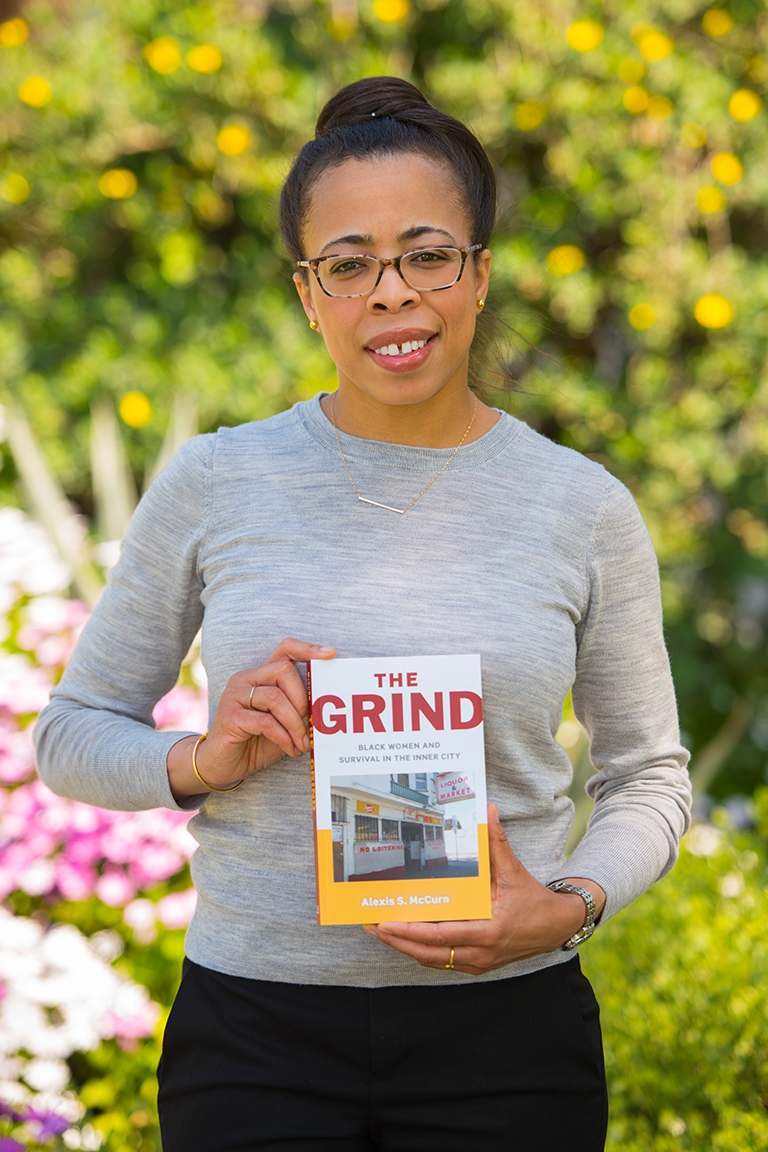

McCurn, an associate professor of sociology at California State University, Dominguez Hills (CSUDH), met Ruth while conducting nearly two years of ethnographic research on the lived experiences of poor African American women and the creative approaches they develop to survive in a community regularly exposed to violence. Her fieldwork in East Oakland has become the basis of her first book, The Grind: Black Women and Survival in the Inner City (2018, Rutgers University Press).

Through narrative accounts told by the women themselves, McCurn underscores the intersections of race, gender, and class and how this shapes the ways black women encounter and are encountered by others in public settings within poor communities.

“With the book, my hope is people take away what is at stake for poor black women as they work to meet the demands of daily life under harsh conditions,” said McCurn. “Their vulnerability to public harassment and to acts and threats of sexual violence each time they ride the city bus, walk to work, buy groceries, or try to cash their paychecks is alarming. Still these tasks must get done. I wanted to uncover the voices of women in these communities and the significance of how that story, in many cases, can be similar for others living under similar conditions.”

More broadly, McCurn’s research and book employs ethnographic research methods that includes participant observation and in-depth interviews. In The Grind, she makes the case that the daily consequences of racialized poverty in the lives of African Americans cannot be fully understood without accounting for the personal and collective experiences of poor black women.

I wanted to uncover the voices of women in these communities and the significance of how that story, in many cases, can be similar for others living under similar conditions. — Alexis McCurn

During her time in Oakland, it was common for McCurn to hear women use “grinding” to describe the intensity and drudgery of the daily work black women do to pay bills and buy food in a neighborhood shaped by underemployment, poverty, and racial segregation.

The grind can take many forms. Most commonly, a woman will adopt a “half-time hustle,” work part-time in a low-wage job or in an entrepreneurial venture in the “underground marketplace,” or become an “urban entrepreneur” themselves.

Ruth’s grind was a half-time hustle. After working at King’s in the day, she and her mother worked as seamstresses at night and on weekends off the books for below minimum wage.

“Ruth’s account sheds light on how structural conditions work to reproduce the conditions under which the ‘grind’ persists and the resulting stress of the physical and emotional labor required to survive the ‘grind,’” said McCurn.

Microinteractional Assaults

While McCurn systematically observed the public encounters and interactions as well as the daily routines of women she identified 75 cases of what are called microinteractional assaults during her fieldwork in Oakland. These negative interactional exchanges are experienced by some African American women when they frequent particular local business, such as check-cashing businesses and grocery stores, and during encounters on the street or in other public spaces.

McCurn addresses several types of hostile encounters in The Grind by sharing stories in detail of incidents she witnessed of African American women trying to navigate interactions with clerks while running errands, or doing things most people take for granted, such as buying groceries–often under “hyper surveillance.”

While she observed a check-cashing store one morning–typically done discreetly while taking notes–she stepped in to help an African American women who was having an antagonistic encounter with the clerk, and subsequently became part of her own study.

“The guy behind the counter said she didn’t have a suitable form of identification. So, I stepped in. “Sir, I think you might be mistaken. This is a California ID.’ His response was, “If you don’t want to follow the rules–if you want to start trouble–then both of you get out,” McCurn recalled.

McCurn began to ponder what had just happened. “My observation and involvement in encounters like these helped me to uncover key ethnographic findings in the book, including the routine microinteractional assaults experienced by women in the neighborhood and the strategies they use to negotiate such encounters. These interactions further revealed the ways in which gender, race, and class inform and shape how public interactions unfold.”

McCurn’s writing also powerfully depicts African American women applying “interactional resistance” during unjustified negative encounters–such as price gouging–in local businesses, or when they chose not to when in a hurry or decide it’s not worth it. She also addresses how women challenge sexual and other forms of harassment on the street in a section called “Buffering.”

“It happens all the time. The question is how do we negotiate it? How do we seemingly try to protect oneself?” said McCurn. “One example I use in the book relates to street harassment and physical violence. When you have women coming from school or work, or at the bus stop, you’ll see how they hold their purses or knapsacks tight in their laps. It is a form of buffering, a space between them and the next person who walks by, or says, or does something to them.”

McCurn continues to conduct ethnographic research. Her current study explores issues of gendered violence, and examines how it unfolds, is experienced, and understood, specifically for women living under conditions of imposed social, political, and economic marginality.

Often blurred by the negativity African American women face in a region as poor as East Oakland was how residents in marginalized communities support each other, according to McCurn, and it often takes a long and expansive study to uncover it.

“It was powerful for me to see how residents in this community work collectively to help navigate poverty in that setting, in part by utilizing informal social support networks,” she said. “This network helps make life in an underserved environment a bit easier to bear. Amid neighborhood violence, limited local resources, and unstable job prospects, being able to rely on neighbors for an exchange of goods and services is vital.”