Professor of Anthropology Jerry Moore and four students, Claudio Carini, Michelle Garcia, Martha Ramos, and Steve Rosales, are in Peru using geophysical techniques to help answer archaeological questions at sites dating from as old as 4700 – 4300 BC and as recent as AD 1400 – 1500. This is their blog. (Note: posts are added with most recent at the top.)

¡Saludos, Tumbes!

Dated: June 11, 2014

Posted by: Jerry D. Moore

This phase of the research is nearly done. We leave for Guayaquil tomorrow and fly the next day back to LAX.

We finished the last bit of fieldwork yesterday morning. Over the last weeks we have conducted ground penetrating radar and magnetometer surveys at three different archaeological sites, walking with the equipment back and forth in parallel east-west transects either 1.0 or 0.5 meters apart. Claudio has calculated that the team has surveyed a total of some 22 kilometers in the process. This was tiring work in the direct rays of the equatorial sun, but the results have been worth it–on many levels.

First, we have new scientific data on three ancient sites. For the Inca provincial center of Cabeza de Vaca, we found a previously unknown, deeply buried adobe wall in the aqllahuasi, the area where project director Carolina Vilchez believes once housed “the chosen virgins”–women dedicated to maintaining the cult of the Sun. In the much earlier site of Santa Rosa, we found traces of previously unknown circular cobblestone structures, buildings that probably date to sometime between 3500 and 3000 BC. And at the earliest site we studied, El Porvenir, we found intriguing traces of other features–possibly floors or cooking hearths–in unexcavated mounds, as well as in adjacent mounds excavated in 2007 that contained dwellings dating to 4500 – 4000 BC.

Second, we have laid the groundwork for future investigations. The results of this relatively brief research will be incorporated into future grant proposals that will (hopefully) fund further research by CSUDH investigators.

Perhaps most importantly, this project has provided CSUDH undergraduates with unique and diverse set of opportunities. They will develop a poster presentation of this project to present at the Society for American Archaeology meetings in April 2015 in San Francisco, as well as at next year’s CSUDH Student Research Day. They have seen what is involved in even a relatively brief season of archaeological research. Most importantly, they have seen a portion of Peru and interacted with the people who live here. The CSUDH undergrads have interacted with a wide cross-section of Peruvians–from archaeologists to cab drivers, from conservators to goat herders–and in those exchanges have gained a deep and enriching experience.

Finally, let me add one last comment: our CSUDH students are outstanding.

This group of CSUDH undergraduates–Claudio Carini, Michelle Garcia, Martha Ramos, and Steve Rosales–are careful scholars, hardworking people, and great folks to have in the field. They represent the tremendous students we encounter at our university. It has been my pleasure and honor to work with them conducting archaeological research in far northern Peru.

¡Saludos de Tumbes!

Ancient cities and temples in the Moche Valley, Peru

Dated: June 8, 2014

Posted by: Michelle Garcia and Martha Ramos

We are waiting to board a bus in Trujillo, Peru for the 10-hour ride back to Tumbes, where tomorrow we begin our last week of fieldwork. This weekend we had the privilege of visiting three archaeological sites in the Moche Valley, 500 km south of our project area.

The first site we visited was Chan Chan, the ancient capital of the Chimú Empire from AD 900-1470. Within Chan Chan’s six square kilometer core lie the remnants of temples, elite residences, ceremonial plazas, and burial platforms. Walking through the site’s enormous adobe walls covered in anthropomorphic and zoomorphic motifs gave us an understanding of the culture’s complexity and the role of this city center in the Chimú Empire.

La Huaca del Sol y de la Luna was the next site on our itinerary. This site belonged to the Moche culture and served as the state’s capital from AD 100-800. Due to a restoration project, we could not visit Huaca del Sol, but our visit was nothing short of amazing. La Huaca de la Luna, an important ceremonial center, is covered with well-preserved murals in bright whites, blues, reds, yellows and black depicting the God Aiapaec and the human sacrifices performed in his honor.

Our last stop was Huaca El Brujo in the neighboring Chicama Valley, another Moche site where we viewed the remains of the Dama de Cao, a well-preserved mummy of a tattooed female ruler. At both Moche sites, the architectural design and polychrome murals provided us with insight to the violent yet powerful existence of this culture.

As we return to work in Tumbes, we are leaving with more knowledge, a deeper appreciation, and a better understanding of the history and archeology of Peru. Although the Tumbes sites we have been working at are still under development, this weekend we saw the potential archaeological sites can have. We hope that the research we are participating in can lead to more great discoveries that will enrich the cultural history of Peru and contribute to our growth as future archaeologists.

Geophysical Survey at El Porvenir, Peru

Dated: June 4 2014

Post by: Claudio Carini and Steve Rosales

Today we packed up our ground-penetrating radar equipment and headed north up the Panamerican Highway to the site of El Porvenir.

It is a 60 kilometer drive to El Porvenir, which is located on the southern bank of the Zarumilla River and two kilometers from the Peruvian/Ecuadorian border.

This site contains six artificial mounds that are the focus of our remote sensing survey. Previous excavations by Dr. Moore at El Porvenir have resulted in a number of archaeological discoveries, such as traces of the some of the oldest dwellings known from northern South America (dating to 4500 BC), evidence for a changing subsistence due to environmental change at the beginning of the Holocene, and obsidian obtained from sources in Ecuador more than 500 km to the north.

Using the ground-penetrating radar we surveyed five separate but contiguous zones at El Porvenir, which would later be compiled into one mass of data. Our goal was to discover and analyze subsurface anomalies and geological characteristics. The ground penetrating radar is capable of detecting structures and other buried large anthropogenic features.

Tomorrow, we will survey the same five zones at El Porvenir with the magnetometer. We hope to learn much more about this site through non-destructive techniques by using both the GPR and magnetometer. Analysis of both data sets will allow us to better comprehend the subsurface of El Porvenir, which will enhance future remote sensing projects in this area. In that process, we may come across a discovery that we hope would contribute to the valuable data gathered up until this point in time. After our research, we hope to have a better idea of what remains hidden at El Porvenir.

Possible Discoveries as Pieces of the Picture Come into View

Dated: May 31, 2014, Tumbes, Peru

Post by: Dr. Jerry Moore

Today we made an important discovery. (We think.)

In the last three days, we moved from the Inca site of Cabeza de Vaca to another, much earlier archaeological site named Santa Rosa. In 2007, I excavated parts of Santa Rosa with a team of Peruvian archaeologists and students. Based on surface indications, we thought we would be excavating a relatively straightforward archaeological problem: the tumbled down walls of a four-sided compound built from adobe bricks. We expected that the walls would have slumped into a rough rectangle, and so (we figured) if we dug a line of test pits across the compound, we could essentially slice across the site–as if it were an apple, cut through the middle and exposing skin, flesh, seeds, and core.

This handy analogy proved utterly inadequate for the ancient reality we encountered.

Instead, we found a confusing welter of archaeological deposits. Walls that went nowhere. Layers of fire-reddended earth, but no evidence of charcoal. An enormous and intact ceremonial hearth, placed in a specially prepared basin 2.2 meters across and as well-finished as a koi pond. Two intrusive provincial Inca shaft tombs, where the decayed skeletons–their bones as fragile as bread crumbs–were buried with fine ceramics, the dusty remains of textiles, copper bracelets, and shell ornaments. And a large circular dwelling, about 26 feet across, with a thick cobblestone foundation.

Although the surface pottery on the indicated a late prehistoric settlement dating to the 15th and early 16th centuries, there was very little pottery anywhere in the site. The other fragments were nondescript plainwares of unknown antiquity.

The radiocarbon dates only added to the confusion. I only got these results months after the excavation was completed (it is a complicated process to export samples), and the dates were shocking. The ceremonial hearth and the large circular stone structure were thousands of years older than the Inca burials, dating to between 3500 and 2900 BC.

The archaeological levels indicated a lengthy, discontinuous and complicated series of human occupations at the site of Santa Rosa, but our vision of the past was partial and kaleidoscopic.

But another piece of the picture slid into view today–seven years after those initial excavations.

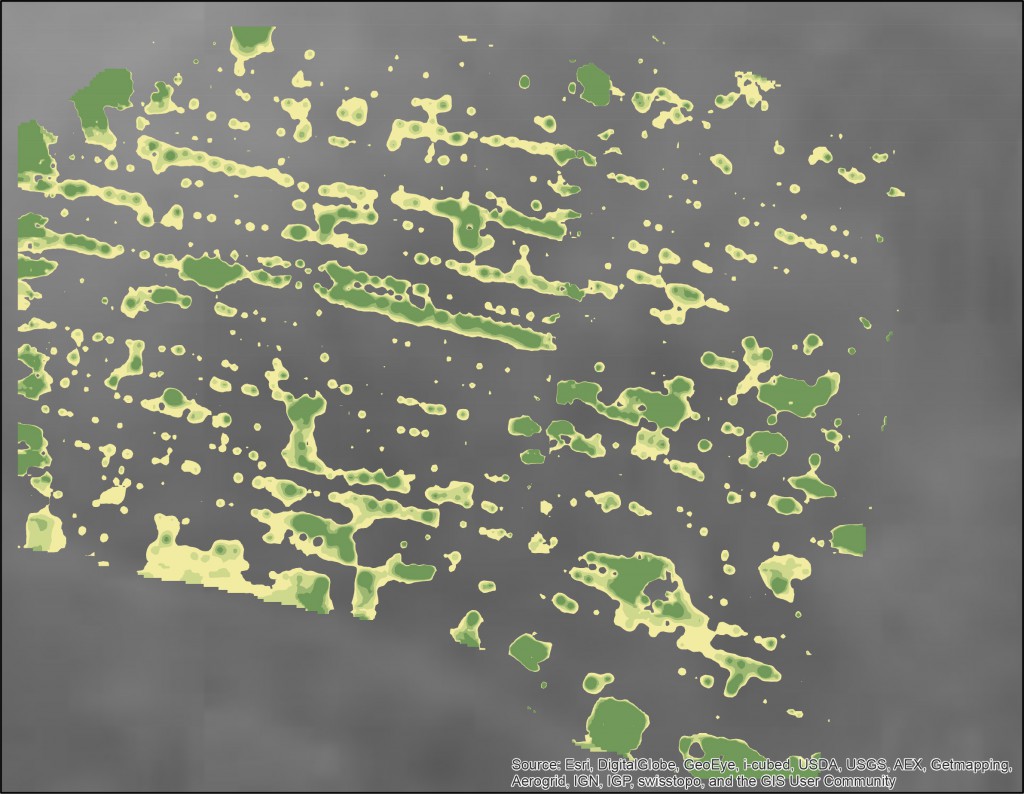

Yesterday we conducted a magnetometer study at Santa Rosa; today we got the results.

We discovered traces of several more circular structures, including one underneath, encircling and predating the later mound that held the Inca burials. It now seems that at one point around 5,500 years ago, Santa Rosa was a small hamlet with big houses. Each large dwelling (roughly 1,400 sq feet) may have housed several related families; maybe 35 – 50 people lived at Santa Rosa at 3500 BC. Before it was a ceremonial space, perhaps it was a domestic space–an architectural transformation worth exploring in future research.

At least that’s what we think today. We’ll see what happens tomorrow.

Learning that using equipment in the field is strenuous

Dated: May 29, 2014

Post by: Michelle Garcia and Martha Ramos

All of our days in Peru begin in the same manner, breakfast on the veranda overlooking the Pacific Ocean, double checking the equipment to make sure nothing is forgotten, and packing it and ourselves into a car. We drive down the Pan-American Highway maneuvering around motor taxis until we reach our destination, the site of Cabeza de Vaca, a major Inca provincial center in Tumbes, Peru.

Our days of fieldwork here have proven to be far from monotonous. Yesterday, we arrived at the site with the magnetometer in tow ready to conduct a geophysical survey of Huaca Del Sol, a temple resting on the Andean road, Qapach Nan. With the help of the archaeologists on site we set two grids needed to serve as a guide when measuring the area’s magnetic fields. By finding anomalies in the data set we could help our colleague, Carolina Vilchez, direct future excavations at the site.

Today we arrived at the site at the same time as yesterday; however, this time we were equipped with a Ground Penetrating Radar. Unlike the magnetometer, which was easily set up in the office and carried by one person to the site, this equipment required teamwork. Each one of us carried a necessary piece of equipment down stairs, steep slopes, and uphill while trying not to hurt ourselves or the equipment.

With the sun blazing and the humidity filling the air, we began our day’s work. Utilizing the same grids set the day before, we collected data by hauling a rectangular antenna over rocky slopes, which proved to be more strenuous than expected. The data acquired through this process could help to identify remnants of walls and artifacts from this urban center.

At the end of the day we gathered in the office, covered in sweat and dirt and seeking comfort from the rotating fans. Donning tired expressions and a sense of accomplishment, we were ready to pack up and do it all over again the next day.

Lost and Found Equipment, Arrival and Setting Up

Dated: May 25, 2014 from Zorritos, Tumbes, Peru

Post by: Dr. Jerry Moore

We are sitting on the veranda of a modest hotel overlooking the Pacific Ocean and checking our research equipment–a ground penetrating radar and a magnetometer–that we will use to investigate four archaeological sites in the next three weeks.

Four CSUDH anthropology students–Claudio Carini, Michelle Garcia, Martha Ramos, and Steve Rosales–will work with me and my Peruvian colleagues, Carolina Vilchez and Wilson Puell Mendoza, to look for deeply buried features at sites dating from as old as 4700 – 4300 BC and as recent as AD 1400 – 1500. These sites represent major moments in South American prehistory, from the origins of settled village life to the expansion of the Inca Empire. Our project will apply geophysical techniques to archaeological questions, the first time these techniques have been used in far northern Peru.

Our weeks of planning seem to have paid off, although the last days of travel have been nerve-wracking and tense. We left LAX on Wednesday afternoon, changed planes in Mexico City with a mad midnight dash to barely catch our connection to Bogota, and then a final flight at dawn to Guayaquil, Ecuador–the closest international airport to Tumbes. We arrived in Guayaquil on schedule. The magnetomer did not. We were assured that it would arrive on the next flight from Bogota. It didn’t. Only later in the afternoon did we receive news that the magnetometer had arrived, but was being held by Ecuadorian customs.

A fitful night’s sleep followed, as I imagined the worse: confiscations, pleadings, and subtle attempts at bribery. Thankfully, we retrieved the equipment effortlessly through the good graces of the customs officials, who listened somewhat incredulously to our explanations–“We are from a university in southern California going to do research in northern Peru”–before waving us through.

The afternoon was spent visiting archaeology museums in Guayaquil, looking at the spectacular objects that prehistoric cultures crafted from clay, stone, and shell.

This was followed a rigorous day of getting ourselves and gear 120 miles south to the Ecuador/Peru border. Although I had rented an entire van, the driver balked at the mountain of gear and luggage we had and insisted that we get an additional van. I suggested that we should just get another driver. This line of argument proved persuasive.

We rode south through vast fields of sugar cane and bananas, emerald plantations under cloudy skies and drizzle. We arrived at the Ecuadorian town of Huaquillas where we were met by Carolina. We then transferred all our gear and ourselves to two other cars, crossed through immigration (Peruvian customs waived us through without a blink), and then south to Zorritos. Marco, the owner of the Hostal Arrecife (a place I have used as my base in past field seasons), welcomed us, and we unloaded gear and luggage once again.

So this morning we have all the gear spread out on the veranda. Batteries were charged. Cables checked. Monitors powered up. Miraculously, everything seems to be working. And our CSUDH undergraduates are a competent, resourceful research team. We are all lucky to be here.