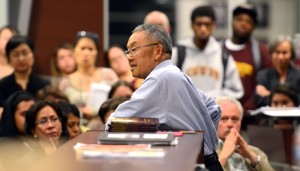

Emeritus professor of history Don Hata spoke on the political, social, and economic issues that led to the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II and the aftermath of the prison camps on Nov. 29 in the University Library, in complement to the exhibit, “Building Evidence: Japanese Americans in Southern California During Mid-Century – 40 Years of Collecting, An Exhibition.” The assemblage of photographs, publications, and documents is focused on the daily lives and obstacles faced by Japanese Americans in the South Bay and Los Angeles prior to, during, and after World War II. “Building Evidence” is now on view through March 2012 in University Archives and Special Collections, which is located in the South Wing of the library.

Hata is the co-author of “Japanese Americans and World War II – Mass Removal, Imprisonment, and Redress,” which he wrote with his late wife Nadine Ishitani Hata in 1974; the book is now in its fourth edition. He addressed a room filled with students and faculty members about the little-known background behind the imprisonment of more than 110,000 American citizens of Japanese heritage. He cited the paranoia of the “Yellow Peril,” a term given to the fear of American and European policymakers of the growing prowess and immigration patterns of China and eventually, Japan.

“By the time the Chinese were driven out in 1882, a federal law had been passed, the first against any immigrant of any nation, specifically saying that they could not immigrate freely to the United States,” said Hata. “In the courts, by 1870, the courts said that a Chinese [person] could not testify on his behalf or be a witness on anybody else’s behalf in the courts of the United States. Plus, the Immigration and Naturalization Service (IMS) interpreted the 14th Amendment as a statement of who was an American citizen; there were native-born citizens and naturalized citizens. [IMS] took it upon themselves to say, ‘Chinese cannot apply for naturalization.’ That’s [what] Japanese immigrants inherited.”

Hata recalled the fear among American policymakers – namely President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and the military – of spies among the nation’s American-born Japanese citizens following the bombing of Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941. Hata described how the fear – and the racism of the times – resulted in the removal and incarceration of Japanese Americans – many of whom had been born in the United States for generations – who lived throughout California and the Pacific Northwest.

“A few months after Pearl Harbor, Franklin Delano Roosevelt signs Executive Order 9066 and it opened the door for military authority to do whatever they needed to defend the United States,” said Hata. “They came up with the rationale of, ‘For the sake of military necessity, we’re going to have to remove all persons of Japanese ancestry from certain designated sites along the Pacific Coast because you can’t trust these people.’”

Hata, a native of Los Angeles, was imprisoned with his family at a camp in Gila River, Ariz., when he was three years old. He said that the decision to incarcerate Japanese Americans served national hysteria over the possibility of spies – and provided a smokescreen for the lack of American dominance over Japan early in the war.

“Six months after Pearl Harbor, the Japanese Imperial Army and Navy were on a roll,” said Hata. “They… had six months of glory, which means the politicians had to find some way to cover up the mismanagement, the lack of preparedness – and they needed a scapegoat.

“I was a fourth-generation American, a U.S. citizen by birthright. But as I and my family, and about 110,000 people were removed from our homes and businesses, guess how we were described? In order to mask the fact that this was happening to American citizens, the bureaucrats cleverly described me as a non-alien.”

Hata described other euphemisms related to the camp experience, many of which were perpetuated by Japanese Americans themselves out of shame for having been imprisoned.

“Many scholars and journalists still get it wrong,” said Hata. “’Internee’ is a very specific, legalistic term. During a time of war, all citizens of the enemy nation can be picked up. But you cannot [imprison] your own citizens.

“A lot of Japanese Americans say, ‘I was interned’ instead of ‘I was in prison.’ We had no dignity and the more you sugarcoat it, the more your fellow Americans will say, ‘It must not have been so bad.’”

Hata revealed the sordid history of the prison camps, which housed Japanese Americans for the duration of the war, long after the Japanese forces were a threat to the United States. He said that the War Relocation Authority (WRA) was established to provide jobs for other Americans who would build camp facilities throughout the Southwest, California, and as far east as Arkansas. In addition, WRA workers oversaw the housing of the Japanese American inmates in the camps, the administration of which was often rife with corruption and mismanagement. Hata underscored the irony of terms like “evacuation” as one of the euphemisms used to describe the camps, and charged students in attendance with developing their critical thinking skills to ensure that something like the Japanese American camps does not happen again.

“This is why we need you to be critical thinkers, more than just readers,” Hata said. “Readers are given instruction. When you can read and disagree, you can write your dissent. If you want to be a teacher anywhere in the system – kindergarten onward – have your students write, because they are defending democracy. They don’t have to shout or scream, all we need is the sound of documentation hitting the desk.

“Yours is the first generation that has an opportunity to strike some sort of balance. [Faculty] don’t have a job teaching here at Dominguez Hills. Teaching here is a privilege… a calling, because we make a difference here. You’re part of a link. So are we. This university is part of … an ongoing process of moving toward a participatory democracy.”