As emergency management and preparedness coordinator of California State University, Dominguez Hills, Gary Singer (Class of ’05, B.A., political science) says that the reality of emergencies is not if they happen, but when. He says that “Operation Jump Start,” a functional exercise that took place last month, was very informative in assessing the university’s readiness for an emergency.

“If you had a drill in which you did everything perfectly, you didn’t have a good drill,” he says. “We have a laundry list of things to improve upon–that’s the good thing about these drills. Small things… that you don’t think about turn out to be very important in an actual emergency.”

With the assistance of students from the California Academy of Math and Science (CAMS) high school on campus and officials from the city of Carson, the university’s team of first responders and emergency managers role-played a scenario that included a catastrophic earthquake, an ensuing fire, and casualties from an automobile accident. CAMS students, who were in theatrical make-up to resemble injury victims, were “tended” to by doctors and staff from Student Health & Psychological Services in a triage exercise. Singer says that the participants worked at providing real-life obstacles for the responders. Firefighters from the Los Angeles County Fire Department, led by Battalion Chief William Mayfield, served as evaluators for the exercise.

“We had exercise controllers from the city of Carson to come help us out and I gave them poetic license to change their condition or ‘kill’ them later to keep it dynamic and to keep the people that were responding on their toes and always making decisions,” he says.

The goal of the exercise, Singer says, was to ascertain that the campus would be self-sufficient for at least 72 hours, with limited or no help from outside agencies.

“Even now, [experts are] starting to say that we need to be prepared even further,” says Singer of the 72-hour guideline. “After Hurricane Katrina, people were left by themselves, or generally by themselves, for days and weeks. In Japan after the tsunami, people had to fend for themselves for longer than 72 hours. You don’t want to rely on the government or [statewide] first responders to come and help you. You want to be self-sufficient so that they can tend to the critical emergencies of people that need saving as opposed to people who just need to be able to feed and shelter themselves.”

Singer says a crucial first response to an emergency would usually be made by the floor wardens of each building on campus, whose main responsibility is to evacuate occupants of buildings to safe locations that are determined by the nature of a situation, communicate missing individuals to the emergency operations center, and keep the campus community informed with updates to the situation.

“Floor wardens are trained once a month, and we are always looking for additional volunteers on campus,” he says.

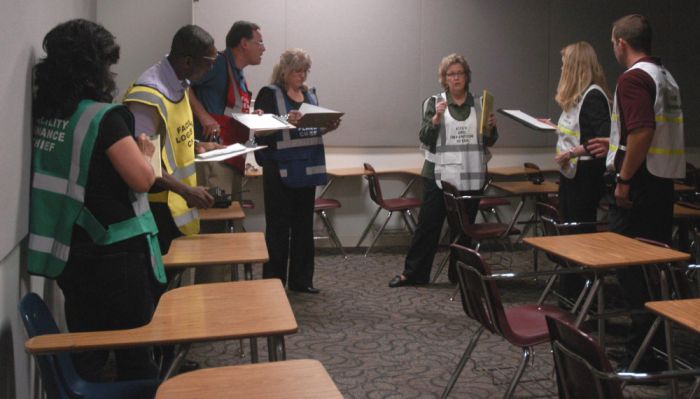

While the hands-on aspects of the Operation Jump Start exercise were addressed by Health Center staff, campus administration and managers were called together in an “Emergency Operations Center” (EOC) in Welch Hall. In the event of an emergency, the EOC team assesses the scope of the emergency and determines what threats to human life and structures exist on campus. Within the EOC there is an operations team that helps direct responses to the disaster and oversees the activities of staff who identify and report hazards such as fires, gas leaks, electrical problems, and structural damage; a planning team that is responsible for the collection and use of information regarding the development of the incident and the status of resources; a logistics team that ensures food, water, first aid and supplies are provided to staff responding to the emergency; a finance team responsible for financial tracking and procurement related to the disaster; and a public information team that issues statements to the media and public on the size and scope of the emergency, progress, injuries or deaths, and care being given.

“The public needs to know important information related to emergency situations on the Dominguez Hills campus as it becomes available,” says Brenda Knepper, director of university communications and public affairs. “Our primary concern is the care and safety of students, faculty, staff and visitors on campus. While we strive to be responsive in emergency situations, we are also obligated to collect information from reliable sources and disseminate accurate facts, so a coordinated approach is taken.”

Emergency communications at CSU Dominguez Hills include loudspeakers throughout campus and speakerphones in classrooms; and an emergency website and phone hotline, both of which are backed up at sister CSU campuses. But perhaps the most important emergency communication system is ToroAlert, which contacts students, faculty, and staff by cell phone, email, text message or home phone in the case of an emergency on campus. Singer says it is important that every member of the campus community keeps their personal contact information in their myCSUDH account up-to-date.

Social media communication has also become key in a state of emergency, and the emergency management and preparedness team has a Facebook page and Twitter account to provide up-to-date information. Those and other social media sites have been valuable in disasters around the world, he says.

“You’ve got things like Flickr and Twitter where emergency managers are able to get [an] idea of what’s going on in their community because people are updating pictures in real time, like damage from earthquakes,” Singer says. “In Christchurch, New Zealand, they had sites up where the emergency managers of the city saw pictures that people were posting for a big picture view of what was going on. It’s faster than they can send people out there to [help]. So it’s dramatically changing the way that people respond now to emergencies.”

Singer says that another important factor in preparing for a disaster at CSU Dominguez Hills is for students, faculty, and staff to be prepared at home.

“There is no way an individual can help the university if their mind is at home with their family and worried about their well-being and safety,” he says. “There are going to be cases where they’re not going to be able to get home. We want them to have that peace of mind that their family is taken care of and know what to do, that they have emergency contacts and meeting places.”

As an alumnus of CSU Dominguez Hills, Singer says that he chose to earn his degree at the university because of its proximity to his former workplace as the assistant emergency preparedness coordinator for the City of Commerce. A year ago, he acquired the position he now holds at his alma mater.

“On a personal level, I thought it would be good to give back to the campus,” he says. “Also, it was a brand new position, so I would be the first and would be able to lay the groundwork for it.”

Because of his connection to CSU Dominguez Hills, the importance of a safe environment for students, employees, and visitors is important to Singer, who says that he wants to emphasize the fact that the university is doing all it can to prepare for the eventuality of an emergency.

“You want to avoid is that feeling that it’s not going to happen here or that there’s only a small chance [an emergency] will ever happen,” he says. “In my field, we get a lot of support and attention right after an emergency happens. It’s always our mission to garner that support and mindset before it happens.”