The third painting in a series to commemorate the 50th anniversary of California State University, Dominguez Hills was unveiled by award-winning artist Hatsuko Mary Higuchi and President Mildred García on May 12 in the fifth floor gallery of the University Library’s South Wing. In addition, emeritus professor of history Donald Hata read from the newly released fourth edition of his seminal work, “Japanese Americans and World War II: Mass Removal, Imprisonment, and Redress.” (Wheeling, Ill.; Harlan Davidson, 2010).

Higuchi, who is based in the South Bay began her painting career after exploring various types of arts and crafts, including metalworking, interior design, and weaving. Her work has garnered top awards at major exhibitions by the International Society of Acrylic Painters, the San Diego Watercolor Society International Exhibition, and the Western Federation of Watercolor Societies. She is best known for her series titled “Executive Order 9066,” referring to President Franklin Roosevelt’s directive that ultimately led to the incarceration of American-born citizens of Japanese ancestry during World War II. Hata’s book, which he originally wrote in 1974 with his late wife, historian Dr. Nadine Ishitani Hata, was a seminal work for its telling of a largely forgotten but shameful chapter in American history.

Donald Hata was born in 1939 in East Los Angeles and incarcerated at age 3 at Gila River, Ariz. Higuchi, who was also born in Los Angeles, was imprisoned with her family as a small child at a camp in Poston, Ariz., from 1942 to 1945. They met at a meeting on Japanese Americans in World War II a few years ago and clashed instantly.

“We sat next to each other totally by accident,” said Hata. “During the question and answer period, Mary found my questions obnoxious and tried very hard to avoid me for the next several meetings. One day, I saw one of her paintings and I thought, ‘Whoa, this is really powerful stuff.’ It took about a year to get rid of her initial feeling that I was so obnoxious.”

Higuchi’s watercolor, “Executive Order 9066, Series 4” graces the cover of the new edition of Hata’s book. In it, a nearly faceless group of Japanese Americans stand waiting after hastily leaving their homes and property with only what they could carry. Text from E.O. 9066 is visible above their heads, oppressive with the conditions of their imprisonment.

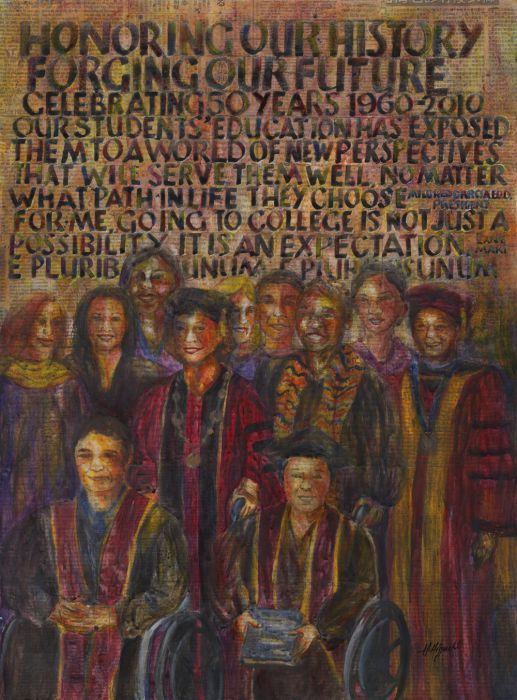

Similarly, “E Pluribus Unum” depicts another expectant group, clad in their graduation regalia. In the background is a collage of text from newspapers in numerous world languages. Above them are quotes from President García and Lane Maki, daughter of acting Provost/Vice President of Academic Affairs Mitch Maki, on the promise and hope of a better life that can be attained through a college education.

“I tried to show diversity in its fullest and most realistic forms, not only of race and ethnicity, but people with disabilities and different age groups,” said Higuchi. “Their commencement gowns represent their unity and common identity as graduates of Dominguez Hills, and the multilingual newspapers in the background show the cultural diversity that ought to pervade the core curriculum and academic programs of any institution that calls itself a university.”

Higuchi, who was an elementary school teacher in the South Bay for more than 40 years, said that she hopes “E Pluribus Unum” will help its viewers realize cultural diversity as “a strength, not a divisive weakness.”

“As viewers see the content of “E Pluribus Unum,” I hope it reminds them that in reality, diversity extends far beyond race and ethnicity,” she says. “There were challenges of teaching children with a variety of talents and needs. The best learning took place when we learned to validate and appreciate each others similarities and differences. We learned to work and learn together and encouraged each other for success.”

Higuchi, who did extensive research of the CSU Dominguez Hills community to create “E Pluribus Unum” by attending a variety of campus events, said that she was impressed by how life at the university “encourages students to apply classroom learning to identifying and supporting real-life issues, and to take active roles in supporting and solving them. They are receiving an education that makes them actively engaged leaders, today and in the future.

“I saw and spoke to many students, who like me, where the first in their families to aspire to a university education,” Higuchi recalled. “Like Ellis Island in New York Harbor, or Angel Island in San Francisco Bay, CSU Dominguez Hills is the port of entry for higher education and the American dream.”

Hata read excerpts from “Japanese Americans and World War II: Mass Removal, Imprisonment, and Redress” and acknowledged two members of the CSU Dominguez Hills community who have also contributed to preserving the history of the Japanese American incarceration. Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga, an activist and researcher who spoke at the university last spring on her essay, “Words Can Lie or Clarify,” which debunks the sugarcoated myths that surround the story of the camps. Hata welcomed her back to the CSU Dominguez Hills campus that evening and also commended the work of Maki, who is also a renowned scholar on Japanese American redress. Maki co-wrote the 1999 book, “Achieving the Impossible Dream: How Japanese Americans Obtained Redress” with the late Harry Kitano, a UCLA professor of Asian American studies and a survivor of the Topaz camp in Utah.

Hata taught at CSU Dominguez Hills for more than 30 years and was recognized with the Lyle E. Gibson Distinguished Teaching Professor Award in 1977 and the CSU Trustees’ systemwide Outstanding Professor Award in 1990. Associated Students, Inc. honored Hata with its Outstanding Professor Award in 1996 and the Teacher of the Year Award in 1998. As a longstanding witness to the university’s growth in the community, he underscored its status over the last five decades as “a powerful agent of change.”

“Over the lifespan of this institution, a tradition has evolved where faculty members across the disciplines are actively engaged with their students in working to understand the unresolved real-life problems, the tough issues that often go undiscussed. We are, at 50 years old, an indispensable asset to the cultural, intellectual, and economic vitality of our region. Over those past 50 years, I have seen this institution come of age and I am proud to have been part of the teaching faculty at California State University, Dominguez Hills.”

President García, who met Hata upon arriving at CSU Dominguez Hills four years ago, said that his gift of “City of Promise: Race and Historical Change in Los Angeles” (Martin Schiesl and Mark Dodge, eds.) in which he and Nadine Hata co-wrote two chapters, was “a wonderful background [to help] an Easterner from New York and a newcomer like me to learn about the diversity of Southern California.”

“Over the last four years, I have had the privilege of getting to know Don as a scholar and someone who cares very deeply about our university as well as about the communities that we serve,” García said. “I value his passion for our students. Many times, an alumna or alumnus has told me that Dr. Hata was one of the professors who made a difference in his or her life. His impact on our students and our campus has been, and continues to be immeasurable.”

Alumnus Martin Chavez (Class of ’82, B.S., Public Administration; ’83, M.P.A.), was present to hear his former professor speak. He recalled an important lesson that had little to do with History 101.

“I remember one time when he gave an exam which I was totally unprepared for, because we didn’t know it was going to happen,” Chavez said. “I looked at the questions and said, ‘I’m not ready for this.’ So I wrote, ‘I don’t know’ for all of the questions, even if I may have known the answer.

“Instead of giving me a grade, he gave it back to me, and on the paper, he had written, ‘By the end of this quarter, you will know.’ And after that, we were the best of friends because we identified each other as individuals who weren’t going to put up with nonsense, but were also going to learn.”

Wynne Ritch (Class of ’72, B.A., history/East Asian studies) was a veteran who decided to pursue his college degree after serving two tours in Vietnam with the Marine Corps. While he was only five years younger than Hata, he said that he learned a lot from being in his East Asian studies classes.

“He showed me what a guy does when he has a passion in his life,” says Ritch. “He showed that passion in his teaching and his people skills with his students. He demanded our skills. I was in the library a lot for Dr. Hata. As a matter of fact, I was in many libraries doing [work] for his classes, because I wanted to write a good paper. He relished new things in his class. He knew he didn’t know everything, so we would have discussions about the things [students] came up with.”

Bill Ota (Class of ’76, B.A., biology) remembered Hata as a professor who “came down like a ton of bricks. He was tough. I thought, ‘This guy is a radical.’ But he was so passionate, you wanted to learn more. I got into discovering my culture, my heritage.

“He pushed students to the max, and wanted them to all do their best. At the time, I was 18, I didn’t appreciate it. Now, I really appreciate him and consider him a mentor. His kind of passion doesn’t come around [often], it’s a rare quality. I’m very grateful to have known him. Sometimes, he still gives me that look of, ‘What are you doing?’ That’s why I dare not give it my best effort.”