Criollo, forastero, trinitario. Varietals with fruity or woody notes. These aren’t wine terms, but rather those regarding cacao–the raw form of chocolate.

Cacao (cocoa), one of the world’s largest soft commodities, is largely produced under complex if not controversial circumstances. The details were served to about 150 California State University, Dominguez Hills students, faculty, and staff during a lecture and chocolate tasting held in the Loker Student Union on Nov. 20.

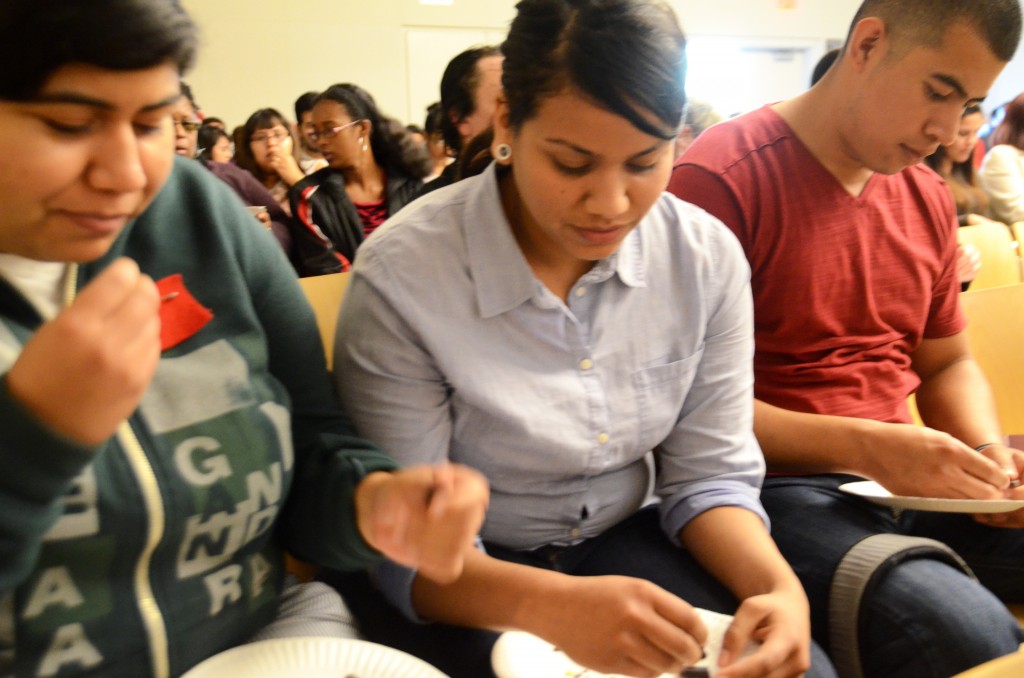

Guests tested their taste buds as they sampled various grades and varieties of finished chocolate handed out on paper plates. The novice chocolate aficionados were provided clues and encouraged to identify the different subtleties and nuances.

The complexity that determines the end product–chocolate–begins with the tropical fruit tree that yields the papaya-sized fruit. The criollo variety of cacao is widely considered to be of the highest quality. But the soil is also an important factor. The better the soil, the more flavorful the plant. All logical. But hang on, Snicker’s lovers, there’s more.

“Everything that’s growing around it, contributes to the flavor of the bean,” said Rebecca Roebber, a U.S. representative for Kallari chocolate who delivered the lecture. “If you have a banana or coconut, passion fruit, wood trees, or mahogany growing around it, the bean will take on those flavors.”

The highly absorbent bean itself will take on the flavor of things it comes in contact with, so during the five- to seven-day fermenting process, workers at the Kallari processing location in the Napo region of the Ecuadorian Amazon are careful to use tools made of certain woods to rake the beans (metal would oxidize the bean, preventing it from fermenting).

“We’re using mahogany [fermentation boxes and rakes], so our chocolate has the taste of mahogany,” Roebber said.

The transference of flavors can be a good thing, but when the beans are transported all over the world it can be a very bad thing.

“You’ll get traces of carcinogens, of oils, the taste of burlap bag, of corn, of things [the cacao] has been transported with,” Roebber pointed out.

The ideal scenario then, it would seem, is to process the bean at the site of its origin. But that’s not the usual practice.

“Traditionally it’s been these tropical countries that produce [the cacao] and it gets shipped off to Switzerland, France, or Hershey, Pennsylvania,” said Janine Gasco, professor of anthropology at CSU Dominguez Hills who invited Roebber to campus. While farmers in third-world countries are growing, harvesting, and fermenting cacao, companies in first-world countries are make the real profits, Gasco said, pointing out that the revolutionary part of the Kallari coalition is that they make the chocolate in the Ecuadorian location where the cacao is being grown. She sees this as a model for operations in other cacao growing regions, such as Chiapas, Mexico, which has been the focus of her research for 30 years.

“I work in this area that has produced cacao for probably 4,000 years. It’s one of the original places where cacao was ever produced as a domesticated plant,” Gasco said. “My research interest is how people in this part of Chiapas have interacted with their environment for thousands of years. [Cacao has] always been in the background of my research, because it answers the question, Why did the Aztecs come to conquer that place? Because they wanted to get the cacao. There is some continuity from the past to the present, in terms of ecological issues.”

During her research in Chiapas, it was her interaction with modern-day cacao farmers that captured her interest in the issue of sustainable cacao production. Unable to afford to continue farming cacao, local farmers in the southern Mexican state would clear their cacao orchards for other uses. In 2000, Gasco began to look for chocolatiers who were interested in buying direct in hopes that the farmers would be able to make a profit and continue a trade that had been a tradition for them for generations.

In 2010, Gasco began leading students in service learning projects in Chiapas, in collaboration with a local nonprofit there, Centro Agroecología de San Francisco de Asís, to work with farmers in their cacao orchards.

“We worked in the fields with the farmers. We helped them prune and removed some diseased pods,” said senior anthropology major Patricia Alonzo, who visited Chiapas, during a 2010 trip as part of an ethno-ecology course taught by Gasco.

The vice president of the Anthropology Club said the experience was so moving that she changed her major, which at the time was kinesiology.

“The lecture brought back a lot of memories,” she said.

As a result of taking students to Chiapas, Gasco said she started learning more about how modern people grow cacao, and the entire processing of the bean, from fermenting to how to get good flavor.

Much like coffee, the roasting of the cacao bean also influences its flavor. Roebber explained that a bitter tasting bean has been under roasted, while over roasting is used to homogenize flavors, especially in the case where inferior beans from different regions of the world are combined. Adding sugar or milk is a technique used to cover up the bad taste of inferior beans. Most milk chocolate products contain between 10 to 30 percent cacao, while high-quality milk chocolate usually contains about 65 percent.

As with coffee, the labeling on chocolate could–and very well may someday–include a rating such as light, medium or dark roast, as well as the origin of the beans.

“The cacao plant originates in Central and South America. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries expanding capitalism took it to these other tropical places, such as Indonesia and Africa, but Africa is where it really took off,” Gasco said.

Although Central and South America produces the most heirloom cacao, where it originates, the Ivory Coast is reportedly the top producer worldwide, followed by Ghana and Indonesia. The origin of the bean is a matter of moral taste as well. Cacao production is successful in the Ivory Coast not only because of ideal conditions in climate, but because it employs child labor, which is cheap. As many as 1.8 million children, between ages 5 and 17, work on cacao farms in Ivory Coast and Ghana, according to an annual report produced by Tulane University.

Gasco and such organizations as Kallari are making small strides in eliminating the use of child labor in the production of cacao. But an educated consumer base, cost of the end product, and big corporations are the biggest hurdles. Gasco and Roebber agreed that local farmers need to be able to make a fair profit to help end child labor in the cacao growing industry.

An initiative requiring all chocolate to be sold in fair trade prompted Hersey, Cadbury, and Nestlé’s to sign an agreement that by 2020 they will only use fair trade chocolate. According to Roebber, Kallari is the only farmer-owned chocolate company in the world, which is even better than fair and free trade systems.

“All of the profits go back to the farmers that grow [the cacao],” she asserted.

Even with all the bad news about chocolate, lecture participants who had been sampling chocolate for an hour seemed to be in good spirits. And why not? Cacao, in arguably its best finished product–high-quality dark chocolate, has been shown to lower blood pressure, boost energy, and maybe even suppress the appetite.